Braun & Borth

Photo by Jeff Silker

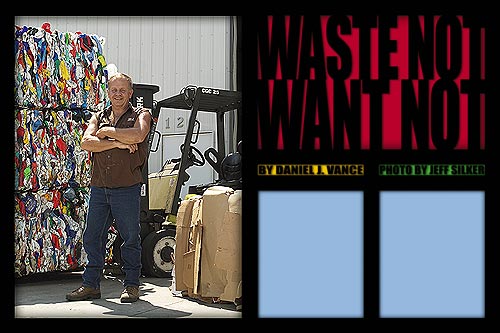

He’d roll up his sleeves if he had any.

Mike Braun, who often goes sleeveless in summer, and his partner Brian Borth both work shifts hauling garbage and “recyclables” over the streets of Sleepy Eye and Springfield. It’s not a job for pansies. The intense heat off fresh tar can almost melt shoe soles, a whiff of rotting fish can be “most interesting,” says Braun, and the only air conditioning in either of their two facilities is an open window in the break room of their recycling center.

Braun can “talk” and “sell” while Borth loves “computers” and “numbers,” a perfect team, which explains why Braun is in the picture at left and Borth isn’t.

The smells may be “interesting,” but to them it’s a decent living. Today they have 12 employees, four trucks, the recycling contract for the western half of Brown County, and the city garbage contracts for Springfield and Sleepy Eye. Since 1991 they have sent off for recycling nearly 7,000 tons of cardboard, tin, aluminum, newspaper, plastic and glass.

Braun was baptized in garbage in 1960 at age 8 when he began helping his uncle Clarence haul trash to the Sleepy Eye city dump. Borth also began lifting metal lids early in life at age 8, but he did it six years later with Mike’s father, Norman.

Mike, now 49, and Brian, 43, have been sole co-owners for the last 20 years.

Garbage hauling today bears no resemblance to the “primitive” methods used in Mike Braun’s first few years in the waste industry. Back then a few people recycled aluminum, but not much else. Car batteries and tires, paint, oil, appliances and all other waste that didn’t breathe or crawl were hauled off to landfills with few if any restrictions.

In the 1960s, some budding Sleepy Eye entrepreneurs were even hauling garbage out to the city dump in their own pick-ups for as many as 100 customers.

Then in 1972, Braun says the landscape changed when, “the [state] closed all the city dumps and forced everyone to county landfills.” It was the “biggest” change he says he has faced in his 30 years in the industry. “Anybody then could haul to the city dump with a two dollar license,” he says. “We could haul for two dollars a year and so could our neighbor. But when the switch to the county landfill occurred everybody had to pay by the cubic yard. So we went to two dollars a year to $16 a load, and we were hauling multiple loads per day.” (It’s $300 a load today.)

In 1972, the City of Sleepy Eye asked Braun’s father, who had the only local dump truck with a compactor, “to haul the whole town for them and be paid for it through city billing on the light bill,” he says. “The City realized that unless it hired someone to haul for them, people would pile up garbage in their backyards.” The city dump had been a convenient mile from town; the new county landfill was 12 miles away. Mike Braun bought into the business when the county landfill first opened.

The Brauns ran a successful father-son business through the rest of the 1970s, and then in 1980 father Norman decided to retire. The buy/sell agreement between he and his equal-partner son stated that any buyers of shares had to be approved by the other. Norman asked Borth, his old lid-lifting buddy, if he were interested in purchasing his half of the business. Borth, then married and working full-time elsewhere, agreed.

Braun says, “And [Brian] has been stuck with half of it ever since. We get along great. We stay out of each other’s hair, and don’t argue about nothing.”

“We have our fields of expertise,” he points out. “He likes computers, and I hate them. He runs billing. I don’t mind talking with people, so I do a lot of the buying and selling, hiring and firing, and I do the welding and painting. We repair all our own dumpsters. We sandblast, paint and put new bottoms in them.”

Both partners work regular shifts in trucks to pick up garbage and recyclables. Even though they have only one “packer” truck, their three recycling trucks also pick up garbage. “Those [recycling trucks] are little hoist trucks,” explains Braun. “They pick up residential trash in the morning while the garbage truck is doing commercial trash. And when they get full, they go find the garbage truck, dump their load, and return to ‘residential.’ When they are done with garbage, they haul compost, and when done with that the same trucks go on their recycling routes.”

He hates “sitting around looking at the same papers every day.” But he loves the outdoors, even in the coldest winter, and believes with all his years in garbage hauling he could never again “give the indoors a chance.” Almost all his employees feel the same, he says, especially the “new guy” recently hired who couldn’t bear his last inside job.

“Winter is better than summer,” he claims. “In winter you can dress for the cold, but in the summer if you dress for the weather you get arrested.”

They have the recycling contract for western Brown County. In 1991, the state government mandated county-wide recycling, and after Braun & Borth won its first recycling contract it quickly constructed a 8,000 sq. ft. facility two blocks from its headquarters to sort, crush and warehouse everything from plastic to glass and cardboard. Brown County subsidizes about 70 percent of the operation, with the remaining 30 percent coming from the sale of recyclable material. The County pays for its subsidy through a “recycling fee” tacked onto all property tax bills.

Braun explains: “We have to go to the County every year with our ledgers to show them what it costs to run the operation — and to project what it’s going to cost to run it the next year.” The County pays out a lower subsidy in years when there are increases in the dollar value on recycling sales.

“It’s a goofy system,” he says, “but it works. It’s fair to the residents of the county. We can’t run the business here just on the money earned from the sale of recycling. If the County didn’t subsidize recycling, it wouldn’t be around.”

Only the sale of corrugated cardboard and aluminum earn a profit. The rest — newspaper, plastic, glass, and tin — are sent out at a loss. They pick up the product commingled at curbside, meaning all recyclables are in the same container, and then drop it off at their recycling facility where it’s sorted by hand the next morning beginning at seven.

Prices fluctuate wildly on corrugated cardboard. When the market dipped in January 2001 to $37 a ton, Braun began stockpiling in the hope of a significant price increase. (It was a logical act: in July 2000 prices were at $100; in previous years, $200.) He had never tried “timing” cardboard before because doing it would have tied up most of his spare warehouse space. But it was a gamble worth taking.

“We didn’t sell any cardboard for six months beginning in January. But then we ran out of room storing it, and had to ship most of it. Our [stockpiling] actually worked because the price shot up to all of $37.50 a ton from $37,” he says with his tongue pressed firmly against the inside of his cheek. If the price had skyrocketed to $100, for instance, the County’s subsidy would have been less, with taxpayers being the main beneficiary. Most of the company’s corrugated cardboard has gone to Liberty Paper Mill in Becker, Minn.

Most newspaper, magazines, office paper and junk mail are backhauled loose to a Nebraska manufacturer to make blown insulation. Another manufacturer shreds it to make animal bedding. Until three years ago the then-bloated market for recycled newspaper often necessitated giving it away.

They have been stung by several plastic recyclers that won’t pay their invoices. “Some of these were established companies recycling too much plastic, and couldn’t find a market for their product,” he says. “They were cleaning bottles and jugs, grinding and chipping them into small pieces, and selling to a manufacturer for melting and remolding. When petroleum prices were falling, and new plastic was being made cheaper, why would anyone buy used when it costs more than new?”

They earn a little more for their aluminum than the average Joe walking in off the street with a paper bag full of Budweiser and Coke cans. That’s because they sell more than three tons at a pop, baled, along with huge bales of tin to a scrap yard in New Ulm. Unlike the aluminum of many off-the-street customers, theirs doesn’t have any hassle associated with it. “We just drive across a truck scale, which is easier for the scrap yard. It’s all about volume,” he says.

“Glass is a dead horse,” he laments, pointing at mounds of cracked green and brown, mostly beer bottles. “The price doesn’t do anything. I think the only reason they recycle some glass is because it makes people feel good. Glass never wears out, and can be recycled thousands of times. But there is an unlimited supply of sand for new glass. Bottle manufacturers can use new sand to make beer bottles for the same price as cleaning up old glass.” They haul all their clear, brown, and green glass to a company in Shakopee.

After the state-mandated recycling in 1991, the flood of recyclable material picked up curb-side drove prices way down and inflated county subsidies. In May 1991, before recycling was mandatory, he was “calling around” for a quote on plastic film and was offered 19-23 cents a pound. After the state mandate, and what had become a glutted market, the price was no better than 3-5 cents a pound.

“Mandatory” recycling is not an accurate description, he says, because it’s not mandatory for residents to place recyclables curb-side. It’s only mandatory that they pay for it. He estimates that almost 50 percent of residential recyclables are carelessly thrown in with the garbage and dumped in the landfill. “When we come in off our residential routes to dump garbage, aluminum cans come out of there by the bag full,” he says. “We could force our customers to recycle by refusing to accept it when we see it in the garbage. But it’s going to have to take the state or county to make a law to have that happen.”

Brown County doesn’t charge commercial accounts the standard $2.25 monthly residential rate for recycling because some businesses require far more service. A retail store, Braun says, could accumulate a ton of cardboard a month, and “there’s no way I can pick that up and process it for $2.25 a month.” So every business contracts separately. Some bars accumulate a thousand pounds of empty beer bottles for recycling each week — glass bottles that are practically worthless on the open market.

Does he have any fear that the County could award the recycling contract to someone else? “They need recycling due to the state mandate, and we stuck our necks out by constructing a new building to accommodate [the County]. The County could run its own recycling center, but it would cost them a lot more.”

Recycling is only half their business. They have exclusive garbage hauling contracts with the cities of Sleepy Eye and Springfield, and are paid by those cities from money tacked onto monthly, city-generated light bills. The exclusivity makes running the business profitable, and therefore worthwhile. He estimates he has about 2,500 residential garbage customers in Sleepy Eye and Springfield. All commercial accounts, as with recycling, are private contracts separate from government control.

© 2001 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.