Nu-Chek Prep

Little-known inside southern Minnesota, 35-year-old, high-tech Elysian fatty acid company has business customers in more than 50 countries.

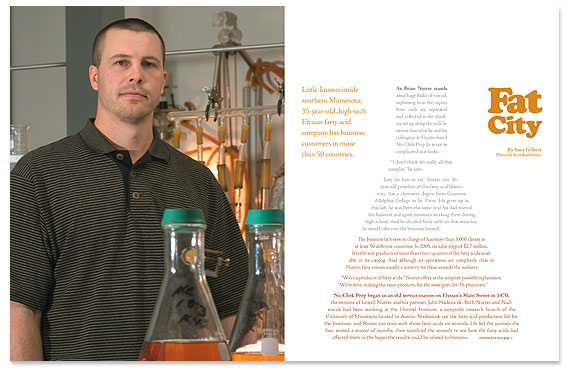

Photo by Kris Kathmann

As Brian Nutter stands amid huge flasks of raw oil, explaining how the vapors from each are separated and collected in the distillery set up along the wall, he swears that what he and his colleagues at Elysian-based Nu-Chek Prep do is not as complicated as it looks.

“I don’t think it’s really all that complex,” he says.

Easy for him to say. Nutter, the 36-year-old president of this fatty acid laboratory, has a chemistry degree from Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter. He grew up in this lab; he was born the same year his dad started the business and spent summers working there during high school. And he decided fairly early on that someday, he would take over the business himself.

The business he’s now in charge of has more than 3,000 clients in at least 50 different countries. In 2005, its sales topped $2.7 million. It is the sole producer of more than three-quarters of the fatty acids available in its catalog. And although its operations are completely clear to Nutter, they remain mostly a mystery for those outside the industry.

“We’re a producer of fatty acids,” Nutter offers as the simplest possible explanation. “We’ve been making the same products, for the most part, for 35-plus years.”

Nu-Chek Prep began in an old service station on Elysian’s Main Street in 1970, the venture of Lowell Nutter and his partner, John Nadenicek. Both Nutter and Nadenicek had been working at the Hormel Institute, a nonprofit research branch of the University of Minnesota located in Austin. Nadenicek ran the fatty acid production lab for the Institute, and Nutter ran tests with those fatty acids on animals. He fed the animals the fats, waited a matter of months, then sacrificed the animals to see how the fatty acids had affected them in the hopes the results could be related to humans.

One day, Nadenicek came in to Nutter’s office and told him about an he had been asked to process. Although the total bill was $4,000, the product necessary would cost only $300. “That’s when the bells started to ring,” remembers Nutter, who had undergraduate degrees in biology and chemistry. As they became more aware that there was a demand for the products they were producing and using, they started talking about building a business of their own.

“The Hormel Institute was more interested in the research side of things,” Nutter says. “We knew there was a market, because we saw the orders that were coming in, and we felt like we could turn it into a for-profit type of thing. So we decided to start our own fatty-acid lab.”

But neither of them really wanted their boss to know what they were planning before it actually got off the ground. They leased the garage across the street from the creamery that Nutter’s father owned in Elysian and had all of their supplies sent there. “We would go up to Elysian on weekends and work on turning that old garage into a lab,” Nutter says. “Eventually, we had to flip a coin to see who was going to tell our boss that we were going to quit. I lost.”

Although breaking the news to his boss at the Hormel Institute was difficult, turning the fledgling fatty acid production plant into a thriving business was far more challenging. Nu-Chek Prep’s first year was especially difficult, partly because of hard feelings down in Austin. “Our boss had a bit of animosity toward us for a while,” Nutter admits. “He kept cutting their prices, so we would have to cut ours too. It got to the point where we knew we just couldn’t cut our prices any further and if he did, we would have to just quit. But he didn’t.”

Eventually, their colleagues at the Institute decided to get out of selling fatty acids entirely, mostly because they couldn’t continue competing with Nu-Chek Prep. And within three years, the business began to break even. With just Nutter, Nadenicek (who retired and left the business several years ago) and a couple of full-time employees, they were able to isolate, extract and purify fatty acids no one else was making.

Most of their acids were derived from vegetable oils; in the early days, they also used porcine liver to produce an essential fatty acid. Today, all the fatty acids, also known as lipids, that they sell are derived from plants: sunflower, safflower, linseed, coconut, palm. They haven’t used any animal products for years. “We don’t use any at all anymore, mostly because of mad cow disease,” Brian Nutter says. “People call all the time to ask about that. They don’t want anything that might have been made with animal products. We would lose a lot of business if we did.”

The original market for Nu-Chek Prep’s acids were universities, colleges, pharmaceutical companies and anyone else interested in using them for research purposes. Having been a university researcher, Lowell Nutter always tried to keep their needs in mind. He had a particular sensitivity to their budget constraints. “I remember when I had to try to buy some of the fatty acids that the Institute didn’t produce,” he says. “They were quite expensive, and we were on a tight budget. So I vowed not to gouge the researcher, to keep the products at a price that they could afford.”

That commitment to moderately priced products continues at Nu-Chek Prep. About half of the company’s sales still go to researchers at colleges and universities. Most of the rest, Brian Nutter says, are sold to distributors, including one in Japan, who purchase Nu-Chek Prep’s fatty acids, repackage them and resell them to their own customers for much higher prices.

“People at trade shows have made comments to me about the fact that my products can’t be any good because they’re so cheap,” Lowell Nutter says. “But then I point out the distributors who sell our product and ask if they buy from them. Usually they do. And so I say, well, that’s our product. It’s important to me to keep it at a reasonable rate so researchers can afford to do their work.”

Nu-Chek Prep still sits on the same site on which it was founded more than three decades ago. Now it is housed in a simple, single-story blue building that takes up, at most, 3,000 square feet. The grand tour, which includes stops in Nutter’s office, the storage room, the lab and the analyzing room, takes less than 15 minutes.

“We’ve had clients who want to come in and take a tour of the facility,” Brian Nutter says. “I always warn them that it will take about 15 minutes to go through the whole place. Most of them don’t understand that we’re a small business, because of the volume we produce.”

Lowell Nutter laughs about the visitor coming round faraway places to tiny Elysian, Minnesota-—a town of about 400 people. “We’ve had people from all over the world who want to come in and go through,” he says. “I tell them that if they come in a business suit, they won’t be let in the door. You have to come very casually.”

Indeed, all is casual at Nu-Chek Prep. There are no white lab coats or stuffy suits; instead, Brian Nutter, the two receptionists and all three of the full-time lab employees (one of whom has been with the company since it began) wear jeans, simple shirts and tennis shoes. Lowell Nutter, who has been “semi-retired” for about the last six years, is in the office only when Minnesota is warm. Usually, he returns from his winter home in Arizona sometime in mid-April and stays until the snow flies. He, too, comes to work in comfortable clothes.

But despite the relaxed appearance at Nu-Chek Prep headquarters, quite serious work takes place there. Raw oils are heated upwards of 450 degrees Fahrenheit so that the predominant fatty acids can be extracted and then purified to 99 percent purity. Often, that purification process involves placing them in a deep freeze that can be set as low as -120 degrees Fahrenheit. Only when the careful analysis process confirms that the acid is pure does the final product go to one of several freezers for storage before being shipped to its final destination.

Brian Nutter says that Nu-Chek Prep offers approximately 1,500 different products in its catalog. Most of them are exactly the same products that his father began producing in 1970. In all the years since, they’ve never encountered much serious competition—the few other companies offering the same products, Nutter says, do so at much higher prices—nor have they had to change their processes in any significant fashion. Although equipment is replaced as it wears out, only the analytical testing machines have seen any serious upgrade in the past 36 years. “At this point,” Nutter says, “we’ll probably never have to replace those again. They’ll last a long time.”

So too will the business. Although Lowell Nutter can’t believe his business venture has had such longevity already, he also cannot foresee a day when there won’t be demand for its product. “You know, it really surprises me,” he says. “After all these years, there’s still a demand for what we do. No one has done it better. I think it’s because these products can’t be mass-produced. Which is the wonderful thing for us, I guess.”

A Tale Of Two Fires

On the evening of November 11, 1997, Brian Nutter was on the sidelines at a high school football game, helping his alma mater, Waterville-Elysian High School. When returning home, he found bad news waiting for him: A fire had broken out at 119 West Main Street in Elysian, the building that housed the business his dad had built from the ground up.

That wasn’t the first time emergency vehicles had been called to Nu-Chek Prep. Twenty years earlier, in 1977, a chemical reaction had sent the whole building up in smoke. The fire started in the morning, while everyone was at work, but fortunately no one was injured in the blaze. The building and everything in it, however, were a total loss. “We lost pretty much everything in that fire,” Nutter says.

The 1997 fire, which started long after business hours, was likely electrical in nature. Again, no one was hurt. But this time, some of the building was spared. “We lost a lot, but we were able to save a lot too,” Nutter says. “The office space and most of the chemicals were saved.”

The process of rebuilding allowed Nu-Chek Prep to expand its space a bit. As the structure went back up, they added two new rooms to the back end, one of which houses the analytical equipment that helps determine how pure their product is.

Although he’s hoping he won’t have to be called down to the scene of another fire to make it happen, Nutter says that within the next two or three years, they’ll likely have to add on to the building again.

Passing It On

There was never any pressure for Brian Nutter to follow in his father’s footsteps and take over the reins of Nu-Chek Prep. But there didn’t have to be. Nutter always knew that’s what he would do.

“I always told Brian that he could do or be anything he wanted,” Lowell Nutter, Brian’s father, says. “But, I said, if you want to go into this business, you have to get a degree in chemistry, so you can answer the technical questions that will come up.”

So, after the three-sport athlete (his proud father reports that he was named Most Valuable Player in football, basketball and baseball his senior year) graduated from Elysian High School in 1989, he enrolled at Gustavus Aldophus College in St. Peter and declared chemistry as his major. Four years later, in 1993, he officially joined the family business. In 2000, he took over day-to-day operations for his father, who decided to enter “semi-retirement” and split his time between Arizona and Minnesota.

Now, when the elder Nutter returns in April to help out at the business, he gets to do all the jobs that his son would rather not handle: answering phone calls, paying the bills and handling payroll. “And I do the crossword,” he says, “and go down to lunch.”

Brian Nutter, meanwhile, is glad for the opportunity to get out of his office and into the lab. “When he comes back, he does all the stuff I don’t like to do,” he laughs. “And get to go back to the lab, which I really like.”

Brian has two sons and a daughter of his own now. Although they are all far too young to even begin contemplating a career in fatty acid production, he says the business is theirs if they want it someday. But no pressure, he says. They can do or be anything they want.

Small Town

Elysian, Minn., has a population of roughly 400. Although it sits on a lovely lake and is surrounded by wonderful woods, most people outside of southern Minnesota have never heard of it.

Except, of course, the more than 3,000 organizations doing business with Nu-Chek Prep.

And although some of those organizations are relatively local—Honeymead in Mankato, for example, and Cargill and General Mills in the Twin Cities—others are decidedly not. Nu-Chek product is shipped to customers around the world. And many of those customers assume that they’re working with a large company in a large space.

Not only is the company’s physical space not large, but the town isn’t either. But that doesn’t matter one way or the other, Nu-Chek president Brian Nutter says.

“The location doesn’t really matter,” he says. “It could work anywhere. If I hadn’t grown up here, maybe I’d go to Arizona and do the same thing. But it works here, and I like it here.”

© 2006 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.