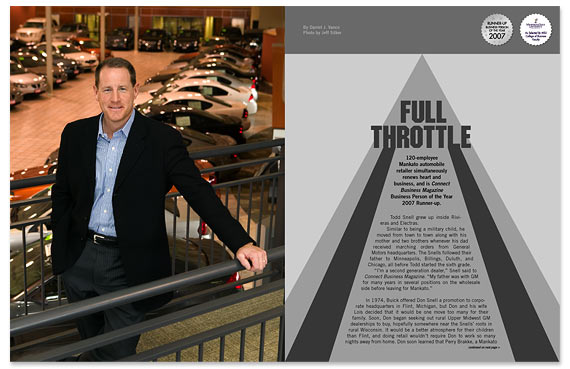

Todd Snell – Runner-Up – 2007 Business Person Of The Year

120-employee Mankato automobile retailer simultaneously renews heart and business, and is Connect Business Magazine Business Person of the Year 2007 Runner-up.

Photo by Jeff Silker

Todd Snell grew up inside Rivieras and Electras.

Similar to being a military child, he moved from town to town along with his mother and two brothers whenever his dad received marching orders from General Motors headquarters. The Snells followed their father to Minneapolis, Billings, Duluth, and Chicago, all before Todd started the sixth grade.

“I’m a second generation dealer,” Snell said to Connect Business Magazine. “My father was with GM for many years in several positions on the wholesale side before leaving for Mankato.”

In 1974, Buick offered Don Snell a promotion to corporate headquarters in Flint, Michigan, but Don and his wife Lois decided that it would be one move too many for their family. Soon, Don began seeking out rural Upper Midwest GM dealerships to buy, hopefully somewhere near the Snells’ roots in rural Wisconsin. It would be a better atmosphere for their children than Flint, and doing retail wouldn’t require Don to work so many nights away from home. Don soon learned that Perry Brakke, a Mankato GM dealer, needed a new partner. Their decision came down to a GM dealership in either Grand Rapids, Minn. or the one in Mankato that had only eight new cars on its lot and faced closing by GM. Don Snell chose Mankato.

Snell Motors was born only four years later, when Don Snell bought out his partner in 1978. Back then the business was scattered all about. Its offices and showroom occupied 1215 North Front, a body shop operated two doors down near the current Honda location, and a used car lot was near the present-day Holiday gas station. Addressing the confusion of his customers, Don Snell sought to consolidate. He brought all three operations under one roof in 1985 by purchasing land and building a new facility not far from the downtown mall. His revenues were more than $1.5 million.

“In 1985 that wasn’t a bad location,” said Todd Snell. “But things would change.”

That same year Snell finished up a several-years string of education experiences that included UM-Duluth, MSU and General Motors Institute. At the new consolidated Snell location on South Riverfront he became a sales manager, and was enjoying good times socially and was racking up impressive sales growth. He had grown up in the business, had even washed cars at the dealership beginning in sixth grade, and felt right at home.

“We had a good honeymoon downtown,” said Snell, “that is, until River Hills Mall was conceptualized and built. The Mall created a whole different dynamic for the city. I knew that we had to get up to the hilltop retail traffic somehow, someway.”

The Snell family instinctively knew where they had to be—they could see the traffic flow—yet moving from South Riverfront to the hilltop posed some risk. Don owned the Riverfront building and property outright, and everyone felt safe there. Perhaps the dealership would have continued operating on South Riverfront Drive until this day if not for the heartache that was started by a chain of events leading to a move. In 1997, Lois Snell died unexpectedly of a brain aneurysm and Don retired almost immediately, leaving Todd and his brother Scott to manage the dealership. They purchased the company from their father soon thereafter.

Though brothers, they had completely different passions, interests and personalities, and different business philosophies. The worries and pressures on Todd’s shoulders about his situation quickly began mounting, and over several months financial pressures increased greatly. With their many differences, Snell realized that either he or his brother had to exit the business or find an outside buyer.

In 1999, Todd went to Arizona to tell his father the news, that he and Scott were splitting, and that he would be moving on. It all would have happened as Todd said, except for an eleventh hour change. “Scott told me at the last minute that he had decided not to buy the business,” he said. Todd telephoned his Wells Fargo banker who chose to back him. Several hours later, attorney Howard Haugh had the sale papers drawn up and Todd was sole owner.

Snell said, “That was the beginning of a different life. We were a seven million dollar company and I paid for a company that didn’t have any blue-sky value at the time. That decision made me look at the reality of Mankato and the traffic flow. I knew for me to justify the price I paid I had to grow the business.”

Instead of moving to the hilltop, like his heart told him, Snell first learned of a car dealership in Jackson that was seeking a buyer. It seemed an ideal situation for Todd to invest in. The location appeared to have great potential and he could use a management contract to do his due diligence before purchasing.

On paper, the dealership showed promise because in its heyday it had sold up to 120 new cars a month. However, by the late 1990s, sales volume had trailed off to fewer than 20. “I went down to Jackson thinking (that growing the business) would be a piece of cake,” said 43-year-old Snell from his Mankato indoor showroom office. “But I was humbled immediately. Jackson was a city of 7,000. I quickly found out that a rural city that size would no longer support the selling of more than 100 cars a month.”

No matter what he tried, sales wouldn’t budge in Jackson, which meant he couldn’t add value. What had happened in Jackson also had hurt hundreds of other GM dealerships and rural cities throughout the United States. Across the country GM’s market share had fallen from its lofty peak in the 1960s, which made domestic car sales all the more difficult. Rural populations had fled to cities as farms failed. Rural towns like Jackson had been losing their hardware, grocery, and clothing stores, and with it the people that would buy all those new cars Snell wanted to sell.

Trying to simultaneously manage dealerships in Jackson and Mankato became a professional and personal nightmare. Emotionally bankrupt, he voluntarily checked into Minnesota-based Hazelden, one of the world’s best-known alcohol and drug rehabilitation centers.

“I’m a recovering alcoholic,” confessed Snell as if he were talking at an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. “After buying out my brother I was using alcohol to numb my emotions and some stresses I was under. Drinking became a crutch to help me deal with life’s problems. After a period of time the drinking paralyzed me. I stopped making critical decisions. It got out of control.” In time, Hazelden would be the tunnel through which he could begin catching a glimmer of hope.

Snell said, “I believe every person ought to take a 30-day timeout at least once in life, regardless of whether they have a chemical dependency problem. When you spend 30 continuous days thinking only of where you are in life and what’s important, you start seeing things clearly. I began to realize that for a number of years I had done nothing but try to make money. Lost in that equation for me was helping people, trying to add value to other people’s lives, and doing the things that if I died tomorrow I’d be proud of. I left Hazelden with a stronger faith in God. If business was only about making money, I wasn’t interested. I would do something else.”

Hazelden offered daily group therapy sessions, relationship building, and education. He successfully learned to curtail his worry and anxiety. He reversed the decision on the Jackson dealership and began to nurture and build Snell Motors in Mankato. Soon thereafter, he went to hear a minister and business coach, John Maxwell, speak about the “21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership.” It was exactly what he had to hear, and the truths rooted deep.

“It was powerful stuff,” said Snell of the next step in his recovery. “I thought a lot about understanding how the dynamics of leadership worked, living my life like that, and training my people at Snell in leadership. I put about half my staff through Maxwell’s training and it changed the company culture. The whole idea of it is how to invest in people and take them to a higher level. I made a commitment after the Maxwell training to be a better leader. Hopefully I am modeling that leadership to others. I look at myself more as a coach or facilitator than a CEO.”

Another aspect of the cultural shift at Snell was a conscious effort to stop focusing on making money—and to start focusing on developing employees and serving customers. In a short time, profits soon became a by-product of business, not the focus, and the company grew at a 25 percent annual clip through 2003.

Snell always felt the hilltop was his destiny. He began by renting the 90,000 sq. ft. former Menard’s building at Madison Avenue and Highway 22 for a one-time indoor car sale, but afterwards thought nothing more of the site. Rather, he had his now-sober heart set on building a 30,000 square foot facility on property purchased along County Road 3. He changed his mind when he and architect Brian Paulsen realized they could remodel the Menard’s site for the same cost.

“They say some of the best things in life you back into,” said Snell. “I’d like to tell you developing this site was 100 percent my idea, but frankly, Menard’s came to me. Our employees and I designed the building based on the idea that a 70-car indoor showroom would offer an experience local people couldn’t get anywhere else. It would differentiate our company and brands. We ended up having more traffic than anticipated. This has taken us from being a $7 million company to $50 million.”

After moving to the new location, Snell’s monthly car sales jumped from 60-80 to 150-200, not to mention a gain in service and parts sales. The dealership now includes Pontiac, Buick, GMC and Cadillac. Only two other GM dealers in Minnesota sell more Buicks, GMCs and Pontiacs.

The airy and cushy interior of the new facility was designed by Paulsen Architects and Snell’s wife Jackie to create a stress-free ambiance for the enjoyment of employees and shoppers. GM initially fought the concept tooth and nail because it didn’t follow a GM template. Since then, GM has done a one-eighty, agreed, and included some of the ideas in a new national dealership program.

As for future growth, “There is nothing stopping us as long as it makes sense for our employees,” said Snell, repeating again concepts learned from John Maxwell. “We want to add value to anything done in the future. As for adding value now, I believe for one we have raised this market’s bar of customer experience. Competition is a healthy thing in this market because it gives consumers more variety and a better experience. We are fully aware that we don’t sell cars to everyone in the market. But still we’ve helped raise the bar. That’s what happens when you compete. We’d love to have a larger presence in southern Minnesota, but only time will tell whether that’s God’s plan. We have more to do here yet.”

Now at his desk looking out onto the world, Todd Snell expressed to the writer appreciation he felt for the many people helping him move forward in life. Perhaps his newfound ability to lean on others for support was something he learned combating the pull of alcohol. He recognized his employees, and especially his wife, who stayed with him through his many battles with alcohol, and also his mentor/father Don, who taught him the automobile business. He also expressed appreciation for architect Brian Paulsen, Wells Fargo and Voyager Bank. Of course, he credited John Maxwell’s training, and God.

Finally, he cited his personal and professional failures as necessary in order to create the fertile soil for his success.

Snell said, “Snell Motors isn’t just about me. I often talk about Snell in the third person, because it’s my employees’ company and its Mankato’s company, too. We do a lot of community fund raising, such as our March of Dimes fundraiser that brought in $120,000. We often try to step away from what Snell Motors is to make sure we’re adding value to people and the community. That is what my life has become. I try to add value wherever I go.”

ROAD TRIPS

We moved from Chicago to Mankato when I was in the sixth grade. It was quite an adjustment. I didn’t have a choice when my dad said we were moving. Yet moving around a lot is part of what has made me who I am. For one, I’m fairly resilient and persistent because of it. Having to make new friends every three years as a child probably helped form that in me. It was a blessing, but at the time I didn’t like it. I have friends who had fathers in the military and they had similar experiences. —Todd Snell

DRIVING LESSONS

Todd Snell today calls father Don his top role model.

“He’s one of those guys who worked hard his whole life,” said Snell. “For me as a child to see him buckle down in business while going through high interest rates and gas prices in the ‘70s and early ‘80s, and seeing his discipline during adversity—he taught me a lot about what it takes to be an entrepreneur.”

The two Snells have vastly differing management styles. “My dad was more hands-on,” said Todd Snell. “Our company today has 120 employees, which means it’s a virtual impossibility for me to have daily contact with every employee. On the other hand, my father came to Mankato when we had less than 20 employees. If there was a diagnostic problem with a car, for instance, sometimes he would roll up his sleeves and get under the hood.”

Snell said the current company culture encourages employees to become actively involved in originating company-wide initiatives, which in turn helps them buy into the changes.

“Nowadays I have my general manager/partner Pat Steffensmeier, my chief financial officer and assistant Tami Menk, both top guns at what they do, and a manager for every department, and they all make their own decisions,” said Snell. “One thing my dad taught me is the value of a mistake made. The question is whether you will learn from a mistake. I believe I’m a better person for having failed and learned from it. Failure for me was a blessing. It is a part of why Snell Motors has gotten where it’s at today. I want to work with a team of people who know and have overcome adversity.”

CO–DRIVERS

My dad taught me a lot about business. Hazelden and faith in God taught me about people and how to treat them —Todd Snell.

BUSY STREETS

Snell said that he didn’t become fully aware of his new site’s regional potential until he regularly began seeing River Hills Mall shoppers from northern Iowa on Saturday afternoons buying cars and driving them home that day. Said Snell, “Now on any given Saturday afternoon we might sell four or five cars, put our customers’ shopping bags in their new cars, and watch them drive home to Iowa. Before moving, I had no idea we would do that.”