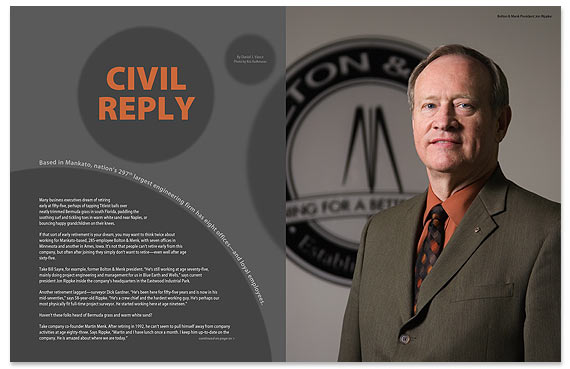

Bolton & Menk

Based in Mankato, nation’s 297th largest engineering firm has eight offices—and loyal employees.

Photo By Kris Kathmann

Many business executives dream of retiring early at fifty-five, perhaps of tapping Titleist balls over neatly trimmed Bermuda grass in south Florida, paddling the soothing surf and tickling toes in warm white sand near Naples, or bouncing happy grandchildren on their knees.

If that sort of early retirement is your dream, you may want to think twice about working for Mankato-based, 285-employee Bolton & Menk, with seven offices in Minnesota and another in Ames, Iowa. It’s not that people can’t retire early from this company, but often after joining they simply don’t want to retire—even well after age sixty-five.

Take Bill Sayre, for example, former Bolton & Menk president. “He’s still working at age seventy-five, mainly doing project engineering and management for us in Blue Earth and Wells,” says current president Jon Rippke inside the company’s headquarters in the Eastwood Industrial Park.

Another retirement laggard—surveyor Dick Gardner. “He’s been here for fifty-five years and is now in his mid-seventies,” says 58-year-old Rippke. “He’s a crew chief and the hardest working guy. He’s perhaps our most physically fit full-time project surveyor. He started working here at age nineteen.”

Haven’t these folks heard of Bermuda grass and warm white sand?

Take company co-founder Martin Menk. After retiring in 1992, he can’t seem to pull himself away from company activities at age eighty-three. Says Rippke, “Martin and I have lunch once a month. I keep him up-to-date on the company. He is amazed about where we are today.”

So why do these people stay on?

Bolton and Menk’s niche has been providing engineering and surveying services to municipalities. It also has a number of private clients. Birthed in St. Peter in 1949 and moved to Mankato in 1965, the company today has its headquarters in Mankato, with other offices in Sleepy Eye, Fairmont, Chaska, Ramsey, Burnsville, Willmar and Ames. To illustrate the firm’s presence in serving southern Minnesota municipalities, Rippke says that Bolton & Menk is the city engineer for every municipality but one along the U.S. Highway 169 corridor from Elmore north to Jordan.

In 1949, the firm began working out of a St. Peter building that would be sold as a garage, should the business fail. Martin Menk and John Bolton struggled for years making a go of it. The old is quite a contrast to the new—the old building in black and white photos looks more like an ice-fishing shack, and the new spacious headquarters features everything from state-of-the-art video conferencing to T1 lines linking all eight offices. As a constant reminder to current and new employees of company growth over the years, a picture of that first building is displayed in all the offices.

One huge early account was the City of North Mankato. Rippke says, “After the company moved to Mankato in 1965, the Minnesota River flooded. We assisted North Mankato in saving its utility systems during the flood. Martin (Menk) told me recently at one of our monthly lunches that our help was a major factor in North Mankato’s decision to start using us regularly. We were a local firm that stepped up to volunteer during a crisis. The flood was quite a disaster for lower North Mankato.”

Rippke really enjoys those monthly lunches, and considers Menk a personal friend. They often travel together after the lunches to work projects, such as a recent one on County Road 41 in North Mankato, the site of a new housing subdivision. At this year’s annual meeting, the company named Menk its honorary chair of the board. As co-founder and president, Martin Menk, says Rippke, “was a very employee-sensitive person, doing a lot of things for employees.” Being employee sensitive included Menk paying for company Christmas parties at the Holiday House in St. Peter, special gifts for employee spouses, and offering generous year-end bonuses. Which explains somewhat why employees tend to stay, but not everything.

Current president Jon Rippke grew up in Moville, Iowa, a tractors-and-diner town of 1,250 near Sioux City. At the same time as graduating from South Dakota State University in 1971 with a civil engineering degree, Rippke through ROTC was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Medical Service Corps (MSC). According to its website, MSC provides highly skilled professionals to “efficiently and effectively” manage a world-class healthcare system in support of the Army. U.S. Army post engineers often came from the Medical Service Corps, Rippke says.

Upon graduation he interviewed with a number of engineering firms, including Bolton & Menk, but none seemed too thrilled hiring a fresh-out-of-college engineer with a non-negotiable two-year military obligation. But the city engineer of Sioux City, Iowa, also an Army Reserve officer, had no problem hiring Rippke without hesitation. After five months there, he received his orders for active duty.

He went through officer basic training at Fort Sam Houston and returned later that year to an Iowa-based Army Reserve unit to begin fulfilling his six-year obligation. Returning to Sioux City, he was a construction engineer for two years before deciding to leave. He realized he needed design experience to pass an upcoming professional exam and he wouldn’t be able to get that experience in Sioux City.

This time Bolton & Menk hired him. Martin Menk’s reasoning was that Rippke had solid experience working with a city engineer—and Uncle Sam likely wouldn’t come calling now that U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War was winding down. When hiring him, Menk hesitated before dropping a potential bombshell: “But the position isn’t here in Mankato. It’s in our Fairmont office.”

Rippke couldn’t have been happier. “To me, moving to Fairmont was great,” he says. “That’s my wife’s hometown. It was a small office with less than ten people. In 1973, I took that job.”

It was a great seven years in Fairmont, filled with solid, resume-building experience. In 1980, Rippke left there for Mankato to help Menk manage certain projects, particularly in North Mankato. And he became more involved in marketing, a skill naturally suiting him. At that time professionals were just beginning to market and advertise their abilities. Previously, Bolton & Menk had been gaining new clients through word-of-mouth, but certain competitors were forcing change, including Twin Cities-based engineering firms that were marketing with both barrels blazing on Bolton & Menk turf.

“I wasn’t bothered at all talking to prospective clients about our company abilities,” says Rippke of marketing. “I just thought our firm was great. I’ve always had a broader, long-term perspective of where the company should go, rather than just focusing on the present. In the early 1980s, our competitors were marketing hard to our clients. We needed to develop a strategy to get out there, too.”

In 1986, as Bill Sayre was named president to succeed Martin Menk, Rippke took over as North Mankato city engineer and began attending city council meetings. Around that time the company grew steadily after purchasing competitor Schnobrich Danielson of Sleepy Eye. It was an exciting time. President Bill Sayre, the firm’s senior engineer, led the charge the next ten years as he commuted daily to Mankato from his Blue Earth home. The company added offices in Burnsville and Willmar to complement Mankato, Fairmont, Sleepy Eye, and Ames, Iowa. Rippke then took over as president in the mid-1990s after Sayre retired—and then didn’t—only to continue working in Fairmont. Since then Bolton & Menk has expanded to include offices in Chaska and Ramsey. With 285 employees, the firm currently ranks No. 297 in size among U.S. engineering firms, according to Engineering News Record.

“We’re not a soup-to-nuts engineering firm,” says Rippke. “Sixty percent of our business, our niche, is providing engineering services to municipalities. We are the city engineers for a number of larger communities without full-time city engineers, including North Mankato, St. Peter, Belle Plaine, Fairmont, Blue Earth, St. James, Sleepy Eye, and Le Sueur.” The Cities of Mankato and New Ulm have their own in-house city engineers.

The consultant city engineer for more than 100 Minnesota municipalities and two in Iowa, Bolton & Menk also is a project consultant to another 130 Minnesota and Iowa municipalities. Larger clients outside the region include the Cities of Big Lake, Buffalo, Mound, and Northfield (on an interim basis). It also serves as the airport consultant for eighteen Minnesota cities, including Blue Earth, Fairmont, Le Sueur, Redwood Falls, St. James, Sleepy Eye, and Mankato.

As the city engineer in smaller cities, such as Elmore and Truman, Bolton & Menk has a wealth of decades-long knowledge of each city’s infrastructure—a knowledge greatly helping new city councils and staff unfamiliar with past projects. The company can help city councils anticipate population growth and any needs to replace or expand water systems, wastewater plants, and city streets.

As for examples of their work, Rippke says, “For Mankato, a larger community, we are doing the airport runway expansion, which includes planning the runway extension, assisting with funding, and working to acquire property and easements. Smaller cities might want us to help them put together a request for a proposal to contractors to paint their city water tower, or design streets for a new subdivision. Or they might want us to figure out whether an old street should be overlaid or milled off, or whether it should be seal-coated, torn up or replaced.” The firm also does construction phase engineering services, which could include surveying and construction inspections.

In the Twin Cities, the firm recently completed a project design for Dakota County on County Road 42 near Burnsville Mall, where commercial and residential growth has caused traffic congestion and over-taxed an aging road system. Bolton & Menk’s design consisted of expanding the roadway to six lanes with protected turn lanes and signalization. Construction is scheduled over a two-year period, beginning this summer.

The company has two divisions. The Environmental division provides water treatment and wastewater treatment services to public and private agencies. This accounts for 20 percent of company revenues. The balance goes to the Civil division, which does most of the municipal work, and surveying. The Environmental division has a number of food processing clients in the Upper Midwest, including Tyson and Seneca Foods (Green Giant).

Another reason employees stay? For one, Bolton & Menk seems to understand the culture and problems of smaller cities because many employees grew up in those same kinds of communities.

“That’s why Bolton and Menk fit so well with me,” says Rippke of his hiring in 1973. “When I started, we worked with a lot of communities the size of Moville, Iowa, where I grew up. I had an appreciation for the issues smaller rural communities faced, such as redevelopment and the ongoing maintenance of existing systems. I grew up knowing people in rural areas are price-conscious and don’t want to pay too much. You can’t gold plate things.”

Today, Bolton & Menk and many of its employees may have rural, southern Minnesota roots, but that hasn’t stopped the company from adopting big-city technology. For one, the company seems to manage well the peaks and valleys of regular business flow, often by redirecting pressing work from office to office. Yet it still is able to keep project continuity. For instance, when the Sleepy Eye office has extra work, it can, though the company’s T1 lines, state-of-the-art video conferencing capabilities, and able project managers, transfer that work to another office. This office-to-office “work-sharing” significantly improves workload management, thus providing employees with a feeling of employment stability.

“We transfer work from office to office all the time,” says Rippke. “It’s as if our offices are working next door to each other. It maintains our efficiency. Video conferencing allows us to have face-to-face discussions among offices with people on the same design team.” The video conferencing allows a manager’s face to be shown on a screen separate from photos of a client’s site, for example. To further marry the offices, each works from common company standards.

Some of the tougher challenges in making the eight offices into a single “virtual office” have arisen from Bolton & Menk’s bold move into the Twin Cities, which began in 1989 to Burnsville and later to Chaska and Ramsey. “When opening Burnsville, our goal was to begin penetrating the Metro market through evolving, growing communities,” says Rippke. “We had been comfortable working in smaller communities. Burnsville was a good way to get our feet wet up there. But we soon learned we had to wear a different hat when working with cities like Burnsville, Inver Grove Heights, Plymouth and Hopkins.”

In order to compete in the Twin Cities, the company had to develop its “areas of expertise” to a higher level, says Rippke. It suddenly was facing issues and situations not usually faced in rural areas, such as complex storm water routing plans through abutting communities, high-volume transportation, and regional government. It challenged employees, and raised the bar.

“We gradually worked our way into it,” says Rippke. “We had a good foundation from the types of communities we’d already been involved in. It was better that way (starting with Burnsville) than jumping right into Minneapolis and trying to work on issues we weren’t prepared to deal with.”

With sixty employees today, the Burnsville office is the company’s second largest after Mankato and its 110 employees. By expanding into new markets, the company also provided much-needed growth opportunities for employees itching to grow professionally.

Finally, another compelling reason employees stay on has been the company’s creative solution toward ownership transition. Many companies unravel at the seams when retiring founders have no other alternative but to sell out to outside owners because a new owner can’t be found internally or locally. Being purchased by an outsider can destabilize any company by lowering company morale because of the potential for downsizing or relocation to another city. Rippke says he receives two or three telephone calls a month from venture capitalists with cash to burn or from larger engineering firms seeking a merger or acquisition. He knows of at least two Twin Cities firms bought by venture capitalists the last few years, and others have merged.

Bolton & Menk solved its ownership transition challenge in the 1980s by creating an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP), which currently holds 30 percent of company stock. A group of thirty-eight company professionals own the balance. Employees can begin owning ESOP shares after only a short period of service. Cash raised through ESOP stock purchases goes to buying out retiring owners and to investing into the company, perhaps for expansion. With an ESOP, Bolton & Menk employees can reap more fruits of their labor, and sleep better knowing the company likely won’t be sold to outsiders. Such a sale would require a shareholder vote.

Says Rippke, “And as the firm’s stock value grows, the value of the shares in the ESOP grow. We build up cash for future stock purchases (from retiring employees). There is a return on the stock fund based on company performance. When leaving or retiring, employees cash out their account.”

With key people working or advising well into their seventies, and with the company being employee-owned, “very” employee sensitive, and having many long-time employees, Rippke says that employees in general—and potential and current customers—feel very positive about the company’s future. Company stability can be a powerful selling tool in a business world of instability.

Public Speaking

From early on in Fairmont, Rippke recognized that his public speaking and marketing abilities could lead to future company growth opportunities. “Today we deal with the public a lot,” says Rippke. “Learning to speak in public is something we stress with our younger engineers. I encourage them to get involved in professional organizations, so they can have opportunities in non-threatening situations to do public speaking. If you do that, and when it comes time to make a presentation to the public about a project or controversial issue, you should be able to do it. Now that we are a larger firm, we are on a bigger stage, such as up in the Twin Cities.”

The focus on public speaking even influences, to a degree, the company’s hiring. Says Rippke, “We hire the best we can, and look at more than just grade-point average. Besides people interested only in a technical track, we look for people with communication skills, or those who have the desire to learn them. We also look for those having a desire to grow in technical areas meeting our needs, such as in water resources or transportation. We are looking for flexible people willing to grow.”

Civil MSU

In 2000, Rippke became concerned after hearing of proposed changes to South Dakota State University’s engineering program and of the state of South Dakota potentially ending its reciprocity agreement with Minnesota for student tuition. As for the latter, if that reciprocity had ended, southern Minnesota students interested in applied civil engineering programs would have had fewer schools from which to choose, and that would have affected Bolton & Menk’s ability to hire quality graduates. Rippke was a South Dakota State University graduate.

The University of Minnesota program emphasizes theoretical versus practical application. In other words, the entire state of Minnesota didn’t have an applied civil engineering program.

Rippke and John Frey, dean of the College of Science, Engineering, and Technology of Minnesota State University, Mankato, talked about the situation. Frey researched the issue, polled engineers, and talked with consultants, and county and state engineers. After Frey documented a need, he and engineering firms like Bolton & Menk helped get the program moving.

“This is the sixth year of MSU’s civil engineering program,” says Rippke, “and it is growing. Today it has over 100 students, and this semester they should be graduating nine. They lose up to 40 percent of the students the first two years. Along the way a certain number change their mind and others are more challenged than they thought they would be.” The goal is to have twenty-five graduates by 2010.

Bolton & Menk hired three of the program’s first six graduates, and has provided intern opportunities for many others. Two company employees teach as adjunct instructors.

Home Town

Says Jon Rippke, president of Bolton & Menk, “My wife’s grandfather started Draper Wholesale, a Fairmont wholesale food and beverage business. He had two sons in the business, Charles and George. The grandfather retired, and the two brothers each had two sons. They split the business into Draper Beverage and Draper Foods. The latter was bought out by Hawkeye Foodservice Distribution.” He says Fairmont is like a second home. While attending nursing school in Iowa, one of his daughters lives in Fairmont and helps keep her grandfather company. The other works in the Burnsville office as a civil engineer.

Rippke, his wife Cheryl, and their two daughters lived in Fairmont from 1973-1980 before moving to Mankato. While there, he was involved with the Fairmont Industrial Development Corp., which helped bring a couple of substantial businesses to town.

© 2007 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.