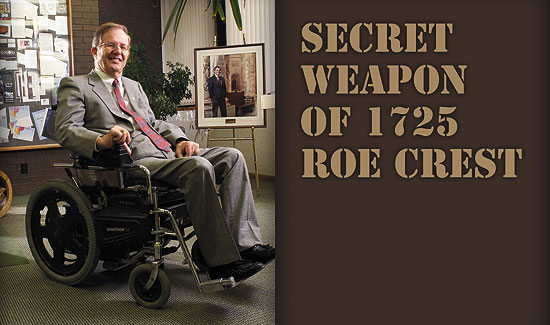

Al Fallenstein

Photo by Jeff Silker

You can hear his high-tech tank approaching now: an Everest & Jennings electric wheelchair on commercial carpet emits a distinctive, high-pitched whirr, signalling “General” Al Fallenstein’s double-time advance to the front lines. While surveying the foxholes at 1725 Roe Crest Drive through powered-up binoculars, he really does seem like a field general leading troops into battle. And in response, the troops stiffen their resolve upon seeing his courage. All that’s missing is a tattered American war flag and a bugler’s charge.

It’s likely Al Fallenstein has never thought of himself as a corporate leader, or an inspiration, but nonetheless he is both and more. If what Napoleon said is true, namely, that “in war, the morale is to the material as three is to one,” then it’s no wonder the 85-division Taylor Corp. army has won so many corporate battles.

His deadly weapon de guerre is an absolutely brilliant business mind. As financial leader the last 25 years of this 15,000-employee, much-more-than-a-billion-dollar corporation, often Fallenstein’s mere insertion into the pitch of a corporate conflict has increased morale among fellow Taylor Corp. executives, who must take great comfort at night knowing that Al Fallenstein is on their side.

At 62, and as Executive Vice President, he boosts corporate morale as much as he did his first day at work in 1975. His gung-ho attitude and unrivaled weaponry are an inspiration — as yet another Taylor Corp. charge up Corporate Hill commences.

CONNECT: What is there about your disability that you consider positive?

FALLENSTEIN: My disability certainly makes me unique: I stand out in a crowd. As for it being a positive or a negative, I’ve never thought of it that way. In fact, I don’t even think of myself as being disabled. I really don’t. I am what I am. Many short people don’t think of themselves as being short. Most people have some disability. Mine is just more visible.

My philosophy is that life is hard, but life is also good. Sure, there are times when young people die, and when bad things happen to good people. But overall, life is good. I’ve learned long ago that life for anyone is made up of peaks and valleys, and I just refuse to get tangled up in the valleys. This isn’t just my own personal philosophy in dealing with my disability, but it’s also a philosophy for business and personal problems — anything and everything.

After my accident in January 1960, I spent two years recovering at Mayo Clinic. People have said to me that the two-year period I spent in that hospital must have been awful. Frankly, I don’t remember that as being a bad time in my life. During my two years at Mayo Clinic I met and saw a number of people who had more problems. It affected my attitude. Like the old saying goes: I felt bad because I had no shoes until I saw a person with no feet.

I’ve always believed that I will walk one day, and I still believe that. Who knows if next week some medical researcher won’t stumble upon a cure for spinal injuries? Of course, I’m not sitting here, waiting for that to happen. The Mayo doctors told me in 1960 that I was a quadriplegic, and that I would likely spend most of my life lying in bed. Their comments deflated my emotions only a day or so.

Having a supportive family has helped. I have four brothers and five sisters who were extremely helpful to me during my transition from Rochester to Mankato in 1962. I also have the world’s greatest wife. Over the years I have received quite a bit of recognition for my business accomplishments — and it goes without saying that my wife Erla of 36 years has been a big part of my success. It wouldn’t have happened without her.

CONNECT: In the 1970s, people with disabilities weren’t accepted nearly as much in the workplace as they are now. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 helped change much of that, by making it possible for people with disabilities to work. How were you able to sell yourself to Glen Taylor, to have him hire you?

FALLENSTEIN: I graduated in the top 5 percent of all MSU accounting majors. I interviewed with many companies that initially seemed to love my resume, but in the end they would reject me because a good portion of their clients’ offices weren’t accessible. I couldn’t find a job. So I opened up my own accounting office in Mankato’s Graif Building. Later, I joined Jaycees, met Glen Taylor and we became friends. I thought very highly of Glen. We would talk for hours about business and our dreams.

But before he eventually hired me, I would first work in Salt Lake City, Sioux City, and St. Paul. In all those cities, Glen and I kept up our relationship over the telephone. He called me when he and two others bought Carlson Craft from Bill Carlson in January 1975, and told me it was time for us to work on our dreams. He believed in me.

I drove from St. Paul to Mankato on a Sunday to meet with Glen, and we both were very excited. When we finished talking, and after he had offered me a position, he couldn’t decide on a salary figure. I told him to pay me what I had been earning in St. Paul, and that at year’s end if I couldn’t show him that I was worth more and that I’d earned my pay, we would deal with it then.

Today, I’m the Executive Vice President, Secretary and Treasurer of Taylor Corporation. After 27 years I still regularly come in Saturdays until noon. Nobody makes me do it. I like being organized for Monday morning.

CONNECT: I’ve heard you worked on a turkey farm as a teen? And now you and Glen are partners in a chicken farm?

FALLENSTEIN: I grew up in North Mankato, and at age 14 began working summers on a turkey farm between Mankato and St. Peter. I lived there too, and made ten dollars a week the first summer, fifteen the second, and twenty the third. It had 3,000 birds, and I thought that was a large operation. Recently, Glen and I started a two-million-bird chicken operation in Iowa.

Like with the chicken farm, I’ve had the opportunity to become involved in and learn many diverse things over my career. These businesses Taylor Corporation owns, or has owned, are interesting. In the ‘80s Glen invested in Valley Bank, and Glen gave me the responsibility of overseeing it. Eventually it expanded to include six banks, and two years ago we sold them for more than $50 million. To me, the best part about overseeing the banks was the personal growth I experienced.

I have had the incredible opportunity to learn about all kinds of businesses and industries. Before lending money you had to learn about the customer’s business, not to mention all I learned about banking and banking regulations. This experience of learning and personal growth wasn’t limited to me, but many people at Taylor Corporation companies have grown over the years as they have taken on their responsibilities at work. It’s like this all over the corporation, from entry-level employees all the way to the top.

CONNECT: Has it been difficult to mix business partnerships with a friendship?

FALLENSTEIN: Glen and I were friends long before we became business partners. If you’re familiar with Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett has his Charlie Munger. Glen has me. He is the best I know at picking people, delegating authority to them, and then moving on. I’m the person who follows up on the details.

We don’t always agree. Over the years he has said that he knows I will honestly tell him my opinions whether I agree with him or not. He likes that because many people are afraid to do that. If a business owner doesn’t have people in the company to tell him their honest opinions, then he’s hearing only one side of the story — his own.

In short, I’m the finance guy, the CPA, the bean counter. I’ve always seen it as my responsibility to be conservative, and if I’m going to err, it will be on the conservative side.

CONNECT: Have there been changes now that Glen is no longer CEO of Taylor Corporation?

FALLENSTEIN: It was a change, sure, but the one constant about business here is change. Glen Taylor was also president of Taylor Corporation, and there will never be another president like him. The business went from being a relatively small company to a very large one, and in that process of growth he was involved in all aspects of the business. The next president couldn’t grow a smaller company to a large one because Glen had already done it. So the next president required an individual with a different style.

Change is part of being a success. Glen and I joke that we’re the dinosaurs here. And eventually it will be important for the dinosaurs to let go, to let the new generation dream in a new way, and to do business a bit differently. Quite frankly, it’s hard for me to let go. I think Glen is much better at it than I am.

CONNECT: Were you surprised that he would let go?

FALLENSTEIN: Glen began learning that lesson in the ‘80s. The first few years he was elected to state senate — and he was a state senator ten years —he ran all aspects of the business. He made all the decisions, with some decisions waiting until he returned from St. Paul. By his eighth year in the senate, our managers were beginning to make their own decisions. At the end of Glen’s tenth year, and upon his return from St. Paul in 1990, the managers didn’t want Glen making their decisions. To Glen’s credit, he was smart enough to realize that by empowering his managers he could grow his business.

CONNECT: How much control does Glen give you?

FALLENSTEIN: It’s scary to think of it. I move millions of dollars every day. I’ve told him he shouldn’t give me that amount of control. (Laughter.) He trusts me, and due to our long-term relationship he knows I’ll take care of my responsibilities. I believe in a system of checks and balances. As a company grows it needs to have internal controls. Before I make a big decision, I like to talk with Glen first. If he’s not available, then I’ll make the decision — business has to go on, decisions sometimes must be made quickly — and with the first opportunity I have afterwards I inform Glen of my decision.

AL’S DAILY BUSINESS REMINDER

Taylor Corp. Executive Vice President Al Fallenstein has a favorite saying framed on his office wall, one that deeply moves him at times. “Courage doesn’t always roar. Sometimes courage is the quiet voice at the end of the day, saying, ‘I will try again tomorrow.’” (Attributed to Maryanne Radmacher Hershey, 1998.)

CONNECT: You’re a big sports fan. You went to Cooperstown for Kirby Puckett’s Hall of Fame induction?

FALLENSTEIN: Yes, and I’m very competitive. In my opinion, competitiveness isn’t just about winning, it also involves playing the game well — and I like to do things well. I’m a baseball fan, and also a huge basketball fan, obviously, because of my ownership in the Minnesota Timberwolves.

I was fortunate enough to have Kirby Puckett invite me to Cooperstown. It was a great day.

CONNECT: Could you take me through the deal you helped create to buy the Timberwolves?

FALLENSTEIN: The Timberwolves deal was interesting in that the former owners thought they had the team sold to a New Orleans group. When the pressure was on to keep the team in Minnesota, they asked Glen if he had an interest in buying the team. One of the first duties Glen assigned me was the task of looking over the numbers, to see if buying a professional basketball team could make financial sense. We didn’t want to buy the team unless we could be financially successful.

We had to put together a plan on how to do it. We talked about many options: how to determine the equity and the portion financed? Who would run the team? By looking at all the numbers we backed into what we could pay for the team. The sellers had their minimum requirements for a selling price because of banking commitments they needed to satisfy. Putting together all the variables was a huge job — and we did it in ten days.

We had a handshake deal in ten days. Then came the tough part: It took almost six months of negotiating with the City of Minneapolis to work out a plan for the Target Center. The City would have to buy it and lease it to us. Negotiating that deal was extremely complicated, with many lawyers and many meetings.

The Timberwolves is not that big of a business. Carlson Craft in North Mankato is a bigger business in terms of revenue and number of employees. Carlson Craft has close to a thousand employees, and the Timberwolves 75. Carlson Craft’s revenues are more than the Timberwolves.

In general, professional sports is a cyclical business: you obtain good players, you win, they age, you begin losing, you earn better draft picks, and theoretically you begin winning again. You come full cycle.

CONNECT: How can a team like the Lakers always seem to stay on top? What’s their advantage?

FALLENSTEIN: Jerry West, the former Lakers general manager, is very astute. Having a good team means having good management, players, draft picks and a good organization. They generated high revenues and could spend more than most teams to get the best players. This will be more difficult under the new NBA salary cap rules.

CONNECT: What happened to offers you made to buy the Twins and Vikings?

FALLENSTEIN: It’s very difficult to make the numbers work in baseball. Small market teams over the long haul simply can’t compete — it’s just not happening. There’s such a massive difference in revenue between the large- and small-market teams. The Twins have a nice, young team right now, but they are losing money. If they’re losing money now, how can they keep that team together for the future?

It’s too early to tell whether the new agreement in baseball will improve the viability of small-market teams. There are people speculating it will. I’m hopeful there will be new ownership in Minnesota to keep the Twins here. I love baseball. It’s part of our quality of life. When we bought the Minnesota Timberwolves, we did it not because we were diehard basketball fans. We felt it was an asset to the entire state of Minnesota, and we didn’t want to lose that asset.

CONNECT: The Vikings?

FALLENSTEIN: The Vikings were another story. There were rumors floating about that the team might leave Minnesota. The former owners thought they had sold to Tom Clancy. When that deal fell through Glen was asked to put together a proposal, which meant we had to spend a good deal of time crunching numbers again.

The former owners were very pleased with the Clancy offer, and Red McCombs’ offer was substantially lower than Clancy’s. We eventually put together an offer that was as good as or better than Clancy’s. Then Red came out of nowhere with his higher offer.

I think Red must have thought of his age and desire to own a team. I don’t think he made the deal with the intent of keeping the team long-term. A team has to be able to sustain itself financially over the long term — and our offer was based on a plan to run the team long-term.

CONNECT: I’ve been told that the Taylor Corp. management team years ago would meet regularly for brainstorming sessions, to come up with ideas on how to improve business.

FALLENSTEIN: What you’re referring to comes from our mission statement; it’s really what we’re all about. We believe there is always a better way to improve how we do business. If anyone knows anything about Taylor Corporation, they know that we continually talk about “opportunities” and “security.” Taylor Corporation is like a beautiful farm: we’re just stewards. When we pass the company on to the next generation it should be better and stronger than when we took control. Hopefully, the next generation feels and thinks the same way. We have to continually take good care of it. We have to keep improving because the competition isn’t just sitting back, doing nothing. Competition is the America way. If you don’t get better, you’re going to be left in the dust.

Yes, we do meet regularly. We talk about the business. I just returned from a three-day meeting with many of our corporate leaders in which we talked about ways to improve the business.

CONNECT: You wear a lapel pin that says, “Opportunity and Security.” You’ve talked some of “opportunity.” What about security?

FALLENSTEIN: That refers to security for our employees at Taylor Corporation. The only real security we have is in the company’s continued ability to earn profits. We don’t apologize for earning profits, and we all work hard for them. If the company didn’t earn a profit, it wouldn’t be employing anyone for long.

The talk of security really isn’t for Glen Taylor or me, because we’ll leave the company one day. It’s about the futures of thousands of Taylor Corporation employees. We’re responsible for that. We want security for the next generation of employees as well. In order to have that we must find the resources today to finance the technology of tomorrow. To have continued security we have to take care of our customers, too. Understanding your customer is the key to success in business.

CONNECT: Glen has been your friend for more than 35 years. You’re one person who tells him what’s on your mind. I’m sure there are times when he disagrees with you. You must have arguments with him.

FALLENSTEIN: When Glen and I have disagreements on which direction to take the business, it’s not a win/lose situation. Sometimes we just have to pause, and think over the issue a few days. While it doesn’t always work out this way, often if we are on opposite poles in a disagreement, after a few days we’ll meet in the middle. We work together to come up with the best solution.

CONNECT: I would assume, too, having been with him so long you’ve made thousands of decisions together. Do you ever look back and think, I wish he would have listened to me then or we wouldn’t be in this mess?

FALLENSTEIN: No. When we decide to go in a direction, as a company we go together in that direction and there is no looking back. I’ve told many of our managers that I’m not sure whether as a company we’ve always made the best decisions, but we’ve always acted on them in unison and made them work.

I think one sign of a good leader is if he can get everyone on his team to focus on the same plan of action. For a leader to have success, the majority of his decisions must be good ones. With Glen that has been the case.

CONNECT: Because Taylor Corporation is a private company, the company isn’t required to release revenue figures. First, how large is Taylor Corp. in terms of employees, and operating divisions — and revenue figures.

FALLENSTEIN: I’ll answer that question in a number of ways. First, we are a large company that doesn’t think of itself as a large company. We are a group of small entrepreneurial companies that operate under the same umbrella. When we started out with just Carlson Craft, a relatively small company, its small size was the key to our success. We’re trying to replicate that Carlson Craft “feel” throughout the rest of our companies.

Taylor Corporation is more than a holding company. We’re also providing financial, managerial, human resource, technology and accounting services to our companies. We run 85 different operating entities and each one has a president or general manager. We tell that person to run the company as if it were their own. We do a good job of planning and budgeting for each entity. When the plan is completed and in place, and we have systems to monitor it, it’s up to the company’s leaders to run their own business.

In terms of size we’re over $1 billion in revenue, with over 15,000 employees. But dollar sales don’t mean a lot in terms of the company’s value. The value added to the raw product is most important. It’s by adding value that we create jobs for our employees and create value for our customers.

We’re not finished building this company. I still enjoy what I do, and Glen enjoys his role. Our company is in the process of developing and adding on a whole new generation of leaders. We’re not finished by any means, and just the thought of more growth gets my juices flowing.

CONNECT: What about personal investments outside the company?

FALLENSTEIN: Obviously, I’m invested in Taylor Corporation. But I’ve also invested in a Twin Cities hotel, a medical products company, the Timberwolves, a restaurant (which failed), a bank group, and a chicken farm. I have studied and invested in many stocks and bonds in the public market over the years. I have always saved and invested part of my pay each year. This practice has served me well.

CONNECT: You’re on the ISJ-Mayo Hospital board. Is healthcare competition good or bad for Mankato? Some say it drives up prices.

FALLENSTEIN: Because of competition, people in Mankato have choices. The medical care in Mankato is improving, and eventually Mankato will become a major regional medical center. Right now there is change, and many people hate change. Mankato Clinic’s new surgery center puts pressure on ISJ-Mayo Hospital, and the new ISJ-Mayo Clinic puts pressure on the Clinic. These are new choices we have. Is this good for people in this region who need medical care? Absolutely.

An interesting item with Mayo Clinic: I was on the negotiating team that merged Mayo Clinic and ISJ Hospital. One thing I insisted on was having community representation on the eventual ISJ-Mayo board. At first, this was hard for Mayo to agree to. Perhaps they thought it would be hard to control the opinions of community members on the board.

My thought was of when we owned six banks, we had local community directors on each. If I couldn’t convince those directors that a course of action was right, then I knew we shouldn’t be doing it. The same can be said for the hospital.

CONNECT: Has it been written into the bylaws that so many board members must be local?

FALLENSTEIN: Yes, the written bylaws state that five of the board members must be local community members. We had some major discussions with Mayo over this issue when we negotiated the affiliation of ISJ and Mayo. It seems odd having spent two years in the Mayo Clinic in 1960-62 as a patient, and then 35 years later being on the ISJ Hospital team that helped negotiate the merger of Mayo and ISJ.

Al Fallenstein Biography

Birthdate: February 4, 1940.

Education: Mankato High School, ‘58; Minnesota State Univ., Mankato, ‘65, Accounting.

Professional Organizations: Financial Executives Institute, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants.

Former and present community involvement: Mankato Jaycees, Rotary, MSU College of Business Advisory Board, MSU Foundation Board, ISJ-Mayo Hospital Board, Courage Center Board.

© 2002 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Pingback: Connect Business Magazine » Off-The-Cuff » Collecting Connect

i didn’t know that about my Grandfather. it sounds like he did great things and i loved him and my grandmother so much. but every year i have to think about it because they both past away before my birthday. but i think what else would they would have done if they were still here with us and i miss them so much.