Wenger Physical Therapy

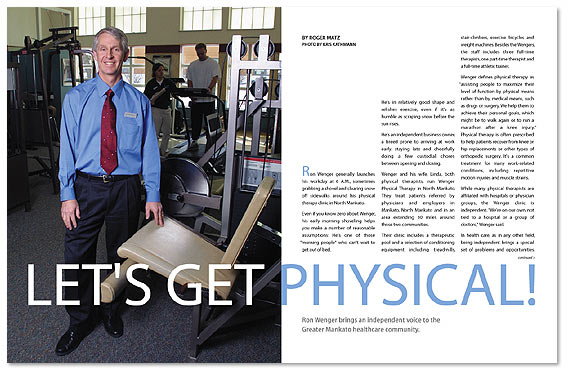

Ron Wenger Brings An Independent Voice To The Greater Mankato Healthcare Community

Photo by Kris Kathmann

Ron Wenger generally launches his workday at 6 A.M., sometimes grabbing a shovel and clearing snow off sidewalks around his physical therapy clinic in North Mankato.

Even if you know zero about Wenger, his early morning shoveling helps you make a number of reasonable assumptions: He’s one of those “morning people” who can’t wait to get out of bed.

He’s in relatively good shape and relishes exercise, even if it’s as humble as scraping snow before the sun rises.

He’s an independent business owner, a breed prone to arriving at work early, staying late and cheerfully doing a few custodial chores between opening and closing.

Wenger and his wife, Linda, both physical therapists, run Wenger Physical Therapy in North Mankato. They treat patients referred by physicians and employers in Mankato, North Mankato and in an area extending 30 miles around those two communities.

Their clinic includes a therapeutic pool and a selection of conditioning equipment including treadmills, stair-climbers, exercise bicycles and weight machines. Besides the Wengers, the staff includes three full-time therapists, one part-time therapist and a full-time athletic trainer.

Wenger defines physical therapy as “assisting people to maximize their level of function by physical means rather than by medical means, such as drugs or surgery. We help them to achieve their personal goals, which might be to walk again or to run a marathon after a knee injury.” Physical therapy is often prescribed to help patients recover from knee or hip replacements or other types of orthopedic surgery. It’s a common treatment for many work-related conditions, including repetitive motion injuries and muscle strains.

While many physical therapists are affiliated with hospitals or physician groups, the Wenger clinic is independent. “We’re on our own, not tied to a hospital or a group of doctors,” Wenger said.

In health care, as in any other field, being independent brings a special set of problems and opportunities.

“We’re better able to provide, or maybe we have to provide, care that’s exceptional, in order to remain in business,” Wenger said. “I wouldn’t say that other therapists don’t do this, but we have to.” He believes patients recognize this independence as an asset. “As a patient walking in the door, it should be reassuring to know we’re independent, that the advice we give is not tied to a relationship that may exist between a physician and a physical therapist. We owe it to a patient to provide an independent, professional opinion about their condition. We feel strongly that patients should be able to choose their own physical therapist, rather than just automatically go where they may be sent.”

Beyond providing exceptional care, the Wengers believe they offer personalized service. “Our niche or purpose is to treat people like family,” Wenger said. That’s often how he frames recommendations to his patients. “I tell them, ‘if you were my grandmother, this is what I’d have you do. Otherwise, you could end up in a nursing home.”

“It’s just like choosing a family physician who knows you as a person, not just as an elbow or a knee,” Wenger said. “We look at the whole patient. If we think their activity is too tough for them, we make suggestions on how to improve their capacity to tolerate that activity. If we feel they need to lose 50 pounds to avoid more injuries, we gracefully try to tell them that. We try to treat patients like family, in their best interests.”

Their need to be independent, to run their own family-oriented business, seems to be in their genes. Linda was raised on a ranch in western Kansas. Ron’s father grew up on a small farm, but started his own real estate and insurance agency in Salina, Kan., after serving in World War II.

“Being independent is part of what you learn from your parents. My dad was a pretty important guy in my life. He ran his own business for years, working full-time until he was 78. I can still bounce things off him,” Wenger said. “When we had trouble coming up with a name for our business, he said ‘if you’re going to run your own business, put your own name on it.’ ”

Wenger “found” his way to a career in physical therapy because of his interest in athletics and exercise. “Like many people going to college, I had no idea what I wanted to do. I had a triple major as a freshman—engineering, pre-med and business. After a couple of years, I dropped engineering because I don’t have an engineering-type brain,” he said. He then dropped medicine “because I didn’t want to stay in school forever,” enrolling instead in the Univ. of Kansas physical therapy program. “I’d always been athletic and found the physical aspect of care interesting, necessary and important.

He found both a career and his future wife in the University’s therapy program. “We did lots of things together…walked, hiked, skied. We still like to do things together.” After graduation, Linda practiced in North Dakota and Wenger joined an independent therapy group in Southern Iowa.

“We carried on a long-distance romance for a couple of years between Iowa and North Dakota,” he recalled. When they married in 1976, Linda also joined the Iowa group.

“These people were really innovative therapists, real trailblazers. They were doing more with back care and joint mobilization. They contracted with 12 to 15 hospitals to provide physical therapy services. They hired people who wanted to work hard, people willing to do a little more and maybe be on the forefront of physical therapy,” Wenger said. “We were always trying something new, something different.”

The experience “whetted our appetite” for a career as independent, innovative therapists, Wenger said. “It’s different, running your own business. You either hate it or you know this is where you need to be.”

In 1978, the Wengers made their move, migrating north to Minnesota. They contracted with the Waseca hospital and a Waterville nursing home to provide physical therapy services. The hospital provided space for a clinic and did their billing. “That was part of the deal, but we bought our own equipment,” Wenger said.

Minnesota seemed a natural place to be. “The roots of physical therapy are right here in Minnesota, with the Sister Kenny Institute treating polio victims, helping amputees from World War II, helping stroke patients recover,” he said.

In 1980, the Wengers expanded, opening an independent clinic in the basement of Mankato’s Orthopedic and Fracture Clinic. “Linda ran Waseca and I ran Mankato. We eventually sold our Waseca clinic to one of our therapists in 1983 and consolidated our efforts here.”

They continued to practice in the style they’d learned with the Iowa group, “doing things a little differently, trying some new things. We had the first Cybex machine in Minnesota,” Wenger said. The Cybex tests a patient’s strength, in an arm or leg, for example. It’s a way of documenting results and determining how much more improvement can be achieved. “We wanted to be more objective in measuring results.”

Their practice flourished, making it impossible to accommodate patients in their 900-square foot basement clinic. In 1988, they built their present clinic, a spacious, airy building at the intersection of LorRay and Commerce Drives in North Mankato. With almost 6,000 square feet on the main floor and 4,000 in the lower level, it dwarfs their former basement clinic. It includes what was—and still is—Mankato’s first therapeutic pool in a healthcare facility. The tall building is highly visible on a corner lot, with large windows jutting up nearly two stories. That allows natural light to spread over their treadmills and exercise bikes.

About 100 people use this conditioning equipment regularly and Wenger estimates that at least three-fourths of them are former patients. “They didn’t want to go to another facility. They felt safer, more comfortable and more supervised here,” Wenger said.

Wenger often rides one of the exercise cycles as a morning-starter on weekdays that tend to begin at 6 A.M. and end 12 or so hours later. “I probably spend 40 hours a week treating patients,” Wenger estimates. He sees patients on Mondays, Wednesday or Fridays, either in the main clinic or in their office at Bethany Lutheran College, which they maintain as a convenience for patients who live in that part of town. The Wengers have provided athletic training services for Bethany teams for many years. “When Bethany built its Sports and Fitness Center, they asked us to have an office there. I see patients there three afternoons a week,” Wenger said.

Tuesdays and Thursdays, Wenger does industrial consulting on safety and ergonomic issues with area companies. “That’s the prevention end of our business,” he said, “although work-related injuries are only about 25 percent of what we do.” Auto accidents also cause some of the injuries the Wenger clinic treats, but most stem from conditions unrelated to such accidents. “Most are caused by aging or by all those things we do to ourselves while we’re playing…twisting an ankle in basketball, falling when skiing, slipping on the ice.”

Wenger began industrial consulting about 15 years ago when executives of an area electronics manufacturer, troubled by frequent workers’ compensation claims, invited him to review their operations. “They had some forward-looking management who wondered if they could prevent some of these injuries or lessen their severity by catching things early,” he said. Now he regularly advises about a dozen companies, taking what he calls a “multi-pronged approach.” That includes an ergonomic analysis of jobs and workstations (is there too much heavy lifting, can repetitive motion be reduced?), job placement testing and injury prevention education for both employees and supervisors.

After Wenger analyzes a workstation, the job process and the way an employee performs tasks, he may make recommendations for changes that will lessen the likelihood of injury. Often these changes are relatively simple. “It might mean moving a computer keyboard slightly, or putting a block of wood under a short person so they don’t have to reach as high, or using a different style of chair to provide better back support,’ he said.

But more often than modifying the job, it’s a matter of making minor alterations in the way an employee performs a job, according to Wenger. “A lot of workstations are set up well, so we take a close look at how they’re doing the work. If somebody has a sore thumb, we watch them working. Maybe they’re doing something wrong with the computer. Early intervention is important. They may never know how it (a minor injury) happened, but we don’t want to let it turn into a big problem that’s hard to fix,” he said.

“Part of it is matching the worker to the job. That means if an employer has a fairly hard job, where somebody has to lift 50 pounds or more, we will bring applicants in and test them to be sure they can do it,” Wenger said. Interestingly, Wenger does less pretesting these days. “Many of the jobs we used to pre-screen for have been changed to make them easier for the employee. They’ve been ergonomically improved. That opens the job up to more people, rather than just a few who are strong enough to do it. Thus it’s easier to find employees and good for employers because worker compensation costs are reduced.”

A good employee education program “is one of the building blocks for helping people understand why it’s important to work in a certain way, to take breaks and stretch or do preventive exercise,” he said. “The Japanese are famous for taking exercise breaks. Some companies require it, but American workers don’t like to be told what to do.”

But when a company calls in an ergonomics consultant, Wenger feels employees should see it as a plus. “I’d say this is a ‘perk’ for employees. If a company is forward-thinking enough to bring in a consultant, they want their employees to feel good. The goal is to have people work productively and not get hurt.”

Wenger finds a relationship exists between employee attitudes and injury rates. “Some people are accidents waiting to happen. Do they like their job? Do they like their supervisor? People who do don’t have as many injuries,” he said. If they are hurt, they’re less likely to have a prolonged recovery. “People who really like their work and want to work aren’t out as long.”

Wenger obviously falls in that category, because he seems to thrive on 12-hour days, seeing patients and consulting with industries. “I enjoy patient care. I get to meet a huge variety of people with different backgrounds, different family situations and work situations. It’s a lot of fun to be a part of their lives and to help them,” he said. “It’s fun being a physical therapist and it’s fun running a business.”

He admires the fortitude displayed by many of his patients. “We have people close to 90 who are still spry. They give us hope that when we get to be that age, we may do as well. I treat a man who’s been a quadriplegic for 40 years. He lives a productive life and he’s happy. He’s an inspiration to me. I have a woman who has multiple sclerosis, who’s striving to stay at a maximum level of function. She doesn’t give up. Patients are often a great inspiration to me.”

Wenger and his wife put in a few work-related hours on most weekends, but they still try to find time to play together. Their current challenge is the Superior Hiking Trail between Canada and Northern Minnesota, which they’re traversing one segment at a time. “There are a lot of hills. It’s really beautiful, but it’s hard hiking. You have to be in good shape. In a weekend, we’ll do 20 miles,” he said. So far they’ve hiked 120 of the trail’s 250 up-and-down miles.

Since coming to Minnesota, the Wengers have raised a family of three youngsters “who all enjoy sports.” Kaettie, 23, is a marketing manager with large Taymark, a Taylor Corporation company, in White Bear Lake. Joel, 21, is an elementary education major at Colorado Christian University in Denver. Pat, 19, is at Gonzaga University in Spokane, WA.

So far, Pat seems to be a bit like his father was three decades ago at the University of Kansas. “He’s undecided,” Wenger laughs.

A Professional Marriage Of Necessity

As much as Ron Wenger relishes his independence, he admits there are drawbacks.

He and his wife Linda own Wenger Physical Therapy, a stand-alone clinic, independent of any hospital or group of physicians.

Independent therapists tend to be so busy with their practice that there’s never enough time to completely untangle the red tape that’s associated with healthcare. Time spent shuffling government or insurance paperwork erodes the hours therapists would rather spend treating patients. And a solo clinic has little negotiating leverage against large insurance companies, which often want to squeeze down rates they pay for medical services.

The Wengers fare somewhat better than many in their situation. That’s partly because Linda no longer sees patients, but concentrates on their clinic’s business aspects. “Because she practiced for many years, she really understands the whole therapy aspect as well as the business aspect,” Wenger said. That’s especially true when she must work with complicated diagnoses and payment codes during the billing process.

About three years ago, the Wengers became part of a rather novel solution to the complexities and challenges faced by independent clinics.

They helped form “Therapy Partners,” a management service organization that provides billing and contracting services. It’s made up of six private physical therapy practices, including the Wengers. The other five are in the Twin Cities. Together, the six owners operate 25 clinics with a staff of 70 therapists. That gives them considerably more clout when negotiating with insurance companies, according to Wenger.

“We’ve actually worked informally with some of these people for many years, exchanging ideas on marketing, service, equipment and personnel management. We started 10 years ago to think about how it could be formalized,” Wenger said.

Therapy Partners now employs 25 in its Maplewood office, most of whom provide billing and other administrative support for member clinics. “Sixty-five percent of our billing is done electronically, not through the mail,” he said.

Therapy Partners’ chief executive officer concentrates on broad issues like personnel, continuing education and contract negotiation. “We do continuing education programs together. We also contract with some insurance companies as a group, which is a definite advantage as opposed to trying to do it alone.”

© 2003 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Pingback: Dun, dun, dun! « Snippets