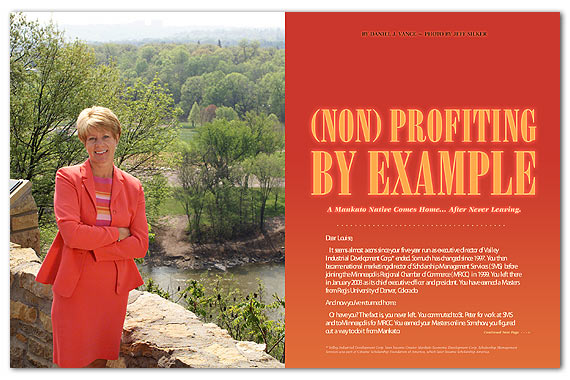

Louise Dickmeyer

Photo by Jeff Silker

Dear Louise,

It seems almost aeons since your five-year run as executive director of Valley Industrial Development Corp.* ended. So much has changed since 1997. You then became national marketing director of Scholarship Management Services (SMS) before joining the Minneapolis Regional Chamber of Commerce (MRCC) in 1999. You left there in January 2003 as its chief executive officer and president. You have earned a Masters from Regis University of Denver, Colorado.

And now you’ve returned home.

Or have you? The fact is, you never left. You commuted to St. Peter for work at SMS and to Minneapolis for MRCC. You earned your Masters online. Somehow, you figured out a way to do it from Mankato.

Let me say again: you figured out a way.

You have this habit, Louise, or should I say “Lou,” of turning the impossible into reality. You figure out ways. You innovate. Perhaps you learned that from your Ph.D. parents. For more than three years you commuted roundtrip three hours daily to Minneapolis and held your family together—all while managing a 24-hour chamber of commerce with thousands of members. On the side you earned a Masters. You did the impossible merging two rival chambers of commerce, Bloomington and Minneapolis. And somehow someway in 2002 you were ranked as one of the Twin Cities’ most influential businesswomen—while living in Mankato.

But that’s old hat. Now you’ve begun from scratch a business that helps nonprofits turn impossible into reality. I’m sure it will succeed. You will figure out a way. You will innovate.

CONNECT: The trend now is for chambers of commerce to consolidate. Last year the Bloomington and Minneapolis chambers merged to create the Minneapolis Regional Chamber of Commerce. Someone told me that merger was your baby.

DICKMEYER: (Laughter.) That wasn’t my baby. I would never say that. However, I was a central figure in the work that brought the organizations together. The merger was a joint effort between volunteers and staff leaders.

For a successful merger to occur both parties must have the right motivation. With nonprofit organizations, that means their defined missions must match or they must have an interest in creating a new joint mission. You also have legal and financial issues in a merger, and due diligence must be undertaken.

In the case of Bloomington and Minneapolis’s merger, the financial affairs of both organizations were scrutinized. The major scrutiny was on Bloomington though, because they were merging into Minneapolis. They had approached us. We reviewed their assets and liabilities. We analyzed outstanding debt, degree of debt, and debtors. We looked into their financial history, and the prospect for continued resources after the merger. All that was filtered into the decision to merge.

CONNECT: Before it reached that stage though, there must have been a critical mass of Bloomington chamber members wanting a merger. Why were they so motivated?

DICKMEYER: I wouldn’t say there was a critical mass, but there were key individuals, well respected in Bloomington, who were broad thinkers. They wanted to have more of an impact on the region, and they knew as a community-based organization that impact was limited. They wanted to engage in lobbying at the state and federal levels, and engage in other areas as well. They wanted a merger with the Minneapolis Chamber as a means to an end. Also, by joining forces with a larger organization they were able to increase for their members the size of their members’ network.

CONNECT: Surely potential for conflict exists between the two groups. For instance, hypothetically speaking, let’s say Bloomington is for light rail. And let’s say Minneapolis has a large faction against it. How do you handle conflicting interests after a merger?

DICKMEYER: When the merger was being developed, the Minneapolis Chamber’s goal was to become more a regional organization than a community organization. We studied other regional chambers, and through that process adopted as our model Charlotte, North Carolina. Charlotte has one regional chamber, and emanating from it like spokes from a wheel are six area councils. The regional chamber administered the area councils, yet within that structure by-law provisions allowed for differences of opinion on political issues. The by-laws stated how those differences of opinion would be handled. For instance, a council could not voice an opinion to the media without also stating that its opinion was not necessarily the position of the regional chamber. Likewise, the merger between Bloomington and Minneapolis allowed for a degree of autonomy.

CONNECT: Let’s try to apply this approach to southern Minnesota. Why couldn’t similar chamber mergers happen here?

DICKMEYER: They could, but as in most mergers if they were to occur, there likely would be problems to work out with loss of independence and identity. I talked recently with an executive of a large metro nonprofit who had gone through a merger. He said that if he hadn’t been forced into it, he would have preferred remaining independent. Mergers can be hard sells. The motivation has to come from bold leadership, and that’s hard to come by. Often the identity and cultures between chambers are so different. Usually it takes a crisis to motivate organizations to merge.

CONNECT: You would think in the least that chambers in southern Minnesota could pool resources to improve their lobbying presence. Many chambers here have shared issues, such as the completion of Highway 14.

DICKMEYER: This region has the Southern Minnesota Highway Partnership, Southern Minnesota Advocates and Voices of Southern Minnesota. These organizations have filled the gap, and are lobbying for region-wide initiatives in cooperation with local chambers. Meanwhile, the various chambers of commerce will keep doing business the same way until their funders demand change.

CONNECT: Healthcare coverage for employees is a big issue for small businesses in southern Minnesota. When you were at the Minneapolis Regional Chamber, was there a move on to introduce a Chamber healthcare plan?

DICKMEYER: It was talked about a lot. If we had been able to offer a healthcare plan for small businesses, we would have increased our membership fivefold. However, Minnesota does not have the right environment for that to happen. For one, we have laws that make the establishment of an association healthcare plan prohibitive. Under current law, a chamber would have a tough time building the necessary critical mass or pool to diminish its risk.

We had in-depth discussions with one major provider that was interested in accommodating the needs of small business owners. But again, there are huge risks in Minnesota, especially if the pool drops below a certain level. If claims were high, and insurance premiums rose because of the high claims, and small businesses dropped out because costs rose, then small business owners would be right back where they started. Those that remain in the pool bear the burden of covering the costs of the plan.

CONNECT: Short of a merger, can chambers of commerce in southern Minnesota in some way pool resources and increase efficiencies?

DICKMEYER: The Minnesota Chamber of Commerce has executive councils throughout the state. The executive councils help local chamber executives share ideas, and keep track of political issues. Open lines of communication are preferable to clear-cut competition.

CONNECT:Why is the Greater Minneapolis Convention and Visitors Association separate from the Chamber?

DICKMEYER: It wasn’t always that way. I was not a part of the history when those two organizations separated. It was my understanding the Chamber’s interests were diverse enough so that the powers that be felt a separate organization necessary. The separation was concurrent with the completion of the Minneapolis Convention Center. The purpose of the GMCVA is to keep the convention center filled. That’s a full-time endeavor. In hindsight, I think they could have made the GMCVA a department of the Chamber.

CONNECT: Dave Jennings hired you at the Minneapolis Regional Chamber. He worked in state government as Speaker of the House and Dept. of Commerce Commissioner, in business with Schwan’s and Associated Builders and Contractors, in nonprofits with the Minneapolis Chamber, and in the public sector again as COO with the Minneapolis school system. It seems he enjoys challenges. Why is he driven to take on so much?

DICKMEYER: Dave is motivated to improve the lot of people – all that he’s done, from Speaker of the House on down to his current position has supported that goal.

CONNECT: Why your attraction to nonprofits?

DICKMEYER: In the year before leaving Valley Industrial Development Corp., I thought long and hard about my career. I was almost 40. While contemplating whether to move on to another nonprofit or go for-profit, I came to the conclusion I liked nonprofits best. First, nonprofits do tremendous work that benefits society. In terms of using the formation of free association to meet social needs, they are the most celebrated sector of our society. In addition, I crave and require variety, and nonprofits provide that with public affairs, board and volunteer development, and marketing and finance. I also hope I’m doing well by helping the community.

CONNECT: Is it important for you to have a purpose behind your paycheck?

DICKMEYER: Yes. Years ago, before it was a cliche, I remember talking with family and friends about wanting to make a difference. Money has not been my motivator. I like having the opportunity in a small way to help change the world.

CONNECT: You once gave a short talk at Urban Currents, a Twin Cities breakfast forum, on the topic “Women in Leadership.” What were your words?

DICKMEYER: That topic was a challenge because it was so important. At the forum I pointed out how extraordinary it was that two women then were top decision makers in federal government: Condoleeza Rice and Karen Hughes. Since then you can add Rep. Nancy Pelosi. I talked of my experience at Valley Industrial Development Corp., which, for the most part during my tenure, had an all-male board. I enjoyed tremendous support from them though, and was voted in unanimously as director. Several of my best supporters in my career have been men.

My main point at the forum: business and society need to look beyond gender. Women should focus on their abilities and their desire to contribute from a personal and professional standpoint, and then move forward. In addition, we also talked about the challenges of balancing work and family.

CONNECT: In 2002 you gave another talk, this one entitled, “Regional Economic Development: Why It’s Necessary.” Why is regional economic development necessary? You have experience running what is now Greater Mankato Economic Development Corp.

DICKMEYER: A regional economic development strategy should overlay a regional economy. Regional economies do not function along geographic boundaries. Regional (rather than community-by-community) economic development is an effective means to attract and retain businesses. When businesses locate to an area, they know they are going to have their employees coming from far-reaching areas. They know their market will be far-reaching. Economies function this way; they don’t have geographic boundaries. It is unfortunate that many folks involved in perpetuating some initiatives are so hung up on turf.

Many business owners investigating Mankato as a possible site are not aware that Mankato and North Mankato are separate cities. I learned that many people in the Twin Cities don’t realize there are two separate cities here. However, they all do recognize that the Mankato area is a regional center. But talk with people here, and it’s a totally different discussion.

CONNECT: Why?

DICKMEYER: Unfortunately, history has an incredible hold on us. I witnessed it at VIDC and in the Twin Cities. In Bloomington, some citizens and state legislators are still angry the Twins and Vikings located in Minneapolis. They still bring it up, even though a nice property tax base exists at the Mall of America, where the old ballpark was. Also, St. Paul feels it must defend itself against Minneapolis or it will be swallowed. That thinking is destructive. It’s a waste of energy, time and resources. It continues because no one is bold enough to say, ‘Enough already.’

CONNECT: So if a business moves to North Mankato, you believe it also benefits Mankato.

DICKMEYER: That’s right. VIDC was formed by bold leaders who recognized the community needed a regional economic development effort. They recognized the organization could work in a neutral manner. They were right then, and that’s the way it should continue today.

CONNECT: In 2002, The Business Journal named you one of the top 25 most influential businesswomen in the Twin Cities.

DICKMEYER: I was humbled by that award. They gave it to our organization as much as me. I happened to be leading the Chamber at the time, and accepted the award on its behalf. We received a great deal of press concerning the merger with Bloomington. It was amazing that Minneapolis and Bloomington, with their histories, came together.

CONNECT: Personally, how tough was it commuting from Mankato to Minneapolis?

DICKMEYER: It took me a year and a half to shed the anxiety before it became routine. And yet it was challenging personally because I was taking three hours of every day away from being with my family. But it was worth it for those three years. However, the commute was part of my motivation for leaving January 31, especially after putting 70,000 plus miles on in the last two years.

CONNECT: Who are your mentors?

DICKMEYER: One person I didn’t realize as such a mentor until several years ago was my mother. She was a full-time professional at a time when women typically weren’t. She helped my father earn his Ph.D., and then she earned a Masters and had a successful career at MSU. After my father died she earned her Ph.D.

Two other mentors were Dave and Sue Jennings. Sue was Valley Industrial’s first executive director and through her I met Dave. She was extremely professional, and exhibited qualities I wanted to emulate. I eventually ended up with her job. As for Dave Jennings, I know of no one more honest and forthright. He is not afraid to speak his mind and stand up for what he believes in. It was an honor and privilege to work with him.

CONNECT: In the last year you earned a Masters online from Regis University. You are also on the MSU College of Business Advisory Council. Do you think MSU could offer an MBA online?

DICKMEYER: I was in on discussions about the MBA program, and in them I encouraged MSU to consider being more innovative than simply offering programs to students seated in desks in front of a lecturer. Many reputable schools offer online programs. Regis, an accredited university, was founded 125 years ago. I had online classmates there from Argentina and other parts of the U.S. It was an incredible experience.

I’m not suggesting that MSU should offer a full-blown, online program. But it can use more innovative ways of delivery. They could extend the college beyond the campus and reach more people. Some schools now have video conferencing, with the instructor miles away from the classroom. Like nonprofits, colleges need to break free of traditional thinking.

CONNECT: With state budget reductions, businesses will be asked to increase their nonprofit contributions. But in a down economy they have less to give.

DICKMEYER: One part of my Masters program was to learn ways a nonprofit can cut expenses and improve service delivery, specifically through creating partnerships, alliances, and informal collaborations with other nonprofits. Nonprofits should first look inward rather than outward to the for-profit sector for help. Often they don’t do that. Often their solution is to seek out more funding, and do business traditionally. Funders can do their part by nudging nonprofits toward innovative solutions.

CONNECT: You’ve helped chambers merge. Why not other nonprofits?

DICKMEYER: That’s part of what my new business does. Many nonprofits have successfully merged. In the Twin Cities, the United Ways of Minneapolis and St. Paul merged. Big Brothers and Big Sisters of Minneapolis and St. Paul merged. But when you use the ‘M’ word, merger, everyone gets nervous.

Short of a merger, nonprofits can still consolidate and/or cooperate. A number of different types of partnerships are possible: two organizations could have a formal restructuring, with a shift of autonomy or local control, such as with a joint venture or joint programming. For example, the Greater Mankato Economic Development Corp., formerly VIDC, has been engaged in a joint promotional effort with the Chamber and the City. Two organizations could have an administrative consolidation and create a parent and subsidiary, where the parent could manage all the human resources or financial management, for example. I’ve written a manuscript on merging nonprofits, and have two book publishers reviewing it now.

CONNECT: In 1998-99 you worked for Citizen’s Scholarship Foundation of America. It’s now Scholarship America. Why the changed name?

DICKMEYER: They were talking about it in 1998. The old name was long and somewhat confusing. They wanted it concise—a name that would better describe their work. Many people have no idea of the operation’s scope. The best-kept secret in Minnesota is that one of the nation’s largest nonprofit organizations is in St. Peter. In terms of size they have consistently ranked as one of the top 70 nonprofits in the U.S. Also, Smart Money Magazine has them highly ranked as an efficient organization.

CONNECT: Tell me about your new business, Nonprofit Innovations, L.L.C.

DICKMEYER: After working with nonprofits 20-plus years, and furthering my education, I wanted to help nonprofits recognize their need for change, and help them implement it. Businesses should know that many nonprofits don’t realize they need change. Many don’t know how to change. Most resist change. In some cases they know they need change but they don’t have the money and staff to implement. I don’t know any nonprofit with an overabundance of money and staff.

The bottom line for a for-profit business is profit. The bottom line for a nonprofit business is its mission. The two worlds are vastly different. A for-profit can raise cash through an IPO; not so with a nonprofit. A nonprofit regards money as an energy source to accomplish a mission. They don’t look at money as cash. It’s not returned as a shareholder dividend.

Constituents, board members, funders, and the public at large, governmental officials, clients that receive services, competition, and staff, all pull nonprofits in different directions. It’s tough duty. To ask a nonprofit manager to bring about change is asking a lot. With Nonprofit Innovations, I’m a free agent. I can look at a nonprofit’s operations, and help them improve by assessing and helping implement change.

Chambers of Commerce

The number of members at selected Chambers of Commerce.*

Greater Mankato 763

New Ulm 360

Fairmont 302

St. Peter 251

Waseca 242

Blue Earth 200

Le Sueur 172

Sleepy Eye 127

St. James 120

Le Center 113

Lake Crystal 91

Madelia 85

Wells 76

Gaylord 65

Nicollet 63

Janesville 48

* Totals are from a Connect Business Magazine telephone survey of May 1, 2003. Membership numbers reveal only so much: some chambers carry nonpaying members and/or have reduced associate or individual memberships.

Get to know: Louise Dickmeyer

Born: February 2, 1958

Personal: Bill, husband; Billy, Tony, and Angie, children

Education: Mankato West High School 1976. Minnesota State University, B.S. and Regis University M.NM

* Valley Industrial Development Corp. later became Greater Mankato Economic Development Corp. Scholarship Management Services was part of Citizens’ Scholarship Foundation of America, which later became Scholarship America.

© 2003 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.