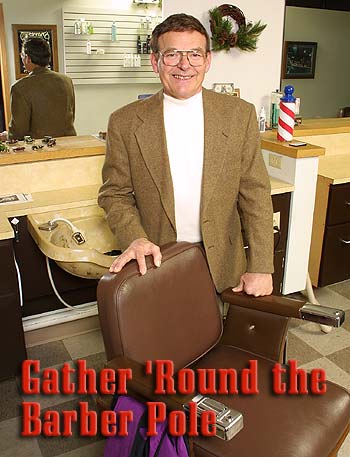

Y Barbers

Photo by Kris Kathmann

Bernie Koenigs began his haircutting career in a drafty supply room at a U.S. Army base in Ankara, Turkey, where he pruned soldier’s hair for a few extra bucks. He had no training. The year was 1958, at the peak of the Cold War.

He had just moved into his supply clerk job after having been in the tedious business of intercepting Morse code for Army Security. The Russian Embassy was only three blocks away from his dot-and-dash cubbyhole at the American Embassy in Ankara. Armed tanks stood guard on the Russian Embassy lawn, their barrels often pointed his way. “I didn’t mind the [Morse code] work,” he says today from his shop location inside Mankato Place, “but there was only one window and one door. I didn’t like being cooped up all day.”

Within a year after transitioning to the supply room, his captain promoted him to staff sergeant. The captain also recruited him to run the base Boy Scout program after learning that Bernie was an Eagle Scout.

With his Army commitment behind him, Bernie headed to Adams, Minn., southeast of Austin, for promised work as a carpenter, but they laid him off within a year. Rather than search for higher-paying work in Austin, he stayed in Adams for a while to eke out a living at the local furniture store. But he felt like he was treading water. His fortunes changed dramatically when he visited St. Paul and happened by the storefront of a barber school, observed through the glass students cropping hair, and decided “that’s what I want to do.”

Bernie had grown up on an Iowa farm that had “cows, beef cattle, pigs, horses and chickens — it was a general farm.” Like most farm boys then, he learned plumbing, electrical, and carpentry work out of necessity. St. Paul Barber College had to have carpentry work done, so he offered his skill.

He breezed through that school, and upon graduation in 1962 set up 14 job interviews. One by one, Bernie spied out each, interviewing the owners — as well as being interviewed — in one talc- and aftershave scented barber shop after another in Minnesota and Iowa. None of them “clicked.” He was a mile away from shop No. 11 when a panorama of trees bearing fall leaves alongside Mankato’s Madison Avenue triggered a sense of peace. Aesthetic by nature, Bernie “knew [Mankato] was the right place even before I had the job. I knew it was going to be my home. I loved it at first sight, and I still love this town.”

He began cutting hair for Y Barbers in late 1962. The shop had been founded in 1904 in the old YMCA building at 2nd and Cherry in Mankato. In 1957, when the YMCA was razed, Y Barbers had to relocate to Front Street next to J.C. Penney’s. Four years later it waggled into the basement of the J.C. Penney’s building where Bernie found it, and where it would thrive for 34 more years. (In 1996, again it had to move, this time to Mankato Place, a stone’s throw from the US Post Office.)

The opening for Bernie had been created when Sven Farland, one of five “Y” barbers, left to start his own barber shop near the MSU campus. He also had an itch to develop a sideline company: Crown Hairpieces (which evolved into present-day Winland Electronics).

The barber industry was sent reeling in the mid-’60s when the Beatles and their hair invaded America via the Ed Sullivan Show and teenagers began screaming for longer hairstyles. “To survive, barbers had to change their method of delivery,” Bernie says. “If you didn’t change you wouldn’t be around. I took classes in the new styles in the Cities. The change was the biggest I’ve ever seen.”

“With teenagers you have to cut their hair the way they want it,” he adds, “and not the way Mom and Dad want. Sometimes the kids were sent back to us because we didn’t cut it short enough.”

Bernie cut hair ten years before buying out his bosses, Bob Klimpel and Odie Tuven. Both had wanted to semi-retire, and fortunately for Bernie, both agreed to work for him after the buy-out. (Klimpel would continue cutting hair at Y Barbers for 17 more years.)

“We have some really prized people as customers,” says Bernie, leaning against a barber chair. “We take care of many MRCI employees. A lot of them melt when we treat them as if they are the most important people in the world. We cut the hair of college and high school students, and hundreds of business people.” Historically, his ratio of male to female customers has been 9:1. (At BK Studio, an affiliated business for hair replacement systems, it’s 1:1.)

The beauty of a haircut has everything to do with the customer’s perceptions. It’s a highly subjective business, he says, and one that can be hurt by negative comments from a coworker or the disapproving glare of a husband. He tries to make his customers happy, but can’t control what goes on outside the shop.

Once a boy came in with his dad. Bernie was on vacation and had hired a part-time barber as a fill-in. The boy glared at his finished haircut in the mirror and barked at his dad, “You’re not going to pay the man, are you?” Bernie straightened out the hair for free when he returned from vacation. In all his years, he has had to refund a customer for a botched haircut only once, though Bernie believes that particular gentleman “just wanted a free one. I don’t think he had a bad haircut.”

Sometimes he must play the role of counselor. “I let customers talk because they want to be heard,” he says. “A woman one day was sharing all her problems. I was trying to help her point by point. Finally she said, ‘If I had wanted somebody to answer these questions then I would have gone to a doctor. I just want somebody to listen.'”

Bernie employs a cosmetologist, Norine Shanks, and two experienced barbers: Larry Thompson, a mainstay for 27 years; and Richard Hebeisen, a five-year veteran.

To raise the bar for his profession he sought a term on the state barber board, and served on it ten years. He also served on the local barber board 22 years until the group disbanded in 1990 after deciding to withdraw support from the national association. “The state barber board lobbies for the profession,” he explains. “A person has to get a license through the state in order to become a barber, and the license must be renewed annually. Each year I have to pay the state $45 for a barber license, $50 for a shop license, and $35 for a cosmetologist license.” In Minnesota aspiring barbers have to pass oral, written, and practical tests. Cosmetologists have their own test.

The state board fashions test content and forwards it to the state legislature which almost always accepts their recommendations as final. Two barbers are appointed to the state board. A barber seeking a board appointment needs at least one friendly politician to act as their advocate.

“It’s unfortunate that Minnesota’s barbers aren’t required to take any tests or classes to renew their annual licenses,” he says with a hint of resignation. “When I was on the board I tried to get ongoing education legislation passed, but the state legislature wouldn’t touch it. A barber group up north said they wouldn’t be able to access the proposed ongoing education because of their geographical isolation. But educators could have travelled to them.”

The Koenigses have a second business, BK Studio, which fits hairpieces for men, women and children going through premature hair loss or chemotherapy. Regional medical institutions have referred hundreds of customers their way. It’s a very personal and private business. Customers are ushered into a secluded suite to ensure privacy. The male to female ratio for this customer base is 1:1

He was dissatisfied with all the hairpiece lines until a salesman entered his shop late one afternoon in 1983. While the salesman waited patiently for Bernie to finish up with customers, he extracted a sample hairpiece from a holding box and began stroking it with a comb. Bernie couldn’t keep his eyes off it. The salesman, Lee Gardner, later became the national sales representative for Florida-based OnRite. Bernie sells the line even today. Almost all hairpieces and wigs are manufactured in Asia, and 90 percent of Bernie’s orders are custom-made. “The industry doesn’t call them toupees anymore,” he says, wincing a bit after hearing the word. “It’s called either hairpiece, hair replacement or hair replacement system.” He stresses that he doesn’t possess the medical credentials for surgical implants.

“Most important in dealing with any hairpiece client,” he says, “is to make them feel good about themselves before putting hair on their head. “We won’t fit a client until I see a smile on their face.” Chemotherapy patients and family members have entered BK Studio crying. Judy, his wife, besides handling the books, works with BK Studio’s female clients.

He has had a solid, 36-year relationship with Judy. They work side-by-side all day, and continue on most nights at home where she runs a Shaklee business. Her personality fits in well with BK Studio. “She is really easy to talk with, and laughs easily,” he says, “and in this business you have to make people happy. She can build a relationship with anyone in a short period of time.”

If asked by relatives, Bernie has provided BK Studio services at funeral homes for his deceased clients. “Someone has to do it,” he says softly.

At 63, he thinks a bit about retiring. “I love coming to work here every day,” he says as he scans the panorama of Mankato’s heritage lining his walls: old B&W snapshots of Front Street, signed Marian Anderson prints, the Saulpaugh Hotel. “I’m going to miss this place. In all those years I’ve never had a day at work that I didn’t enjoy.”

If he retires, he’ll probably end up as a troubadour of sorts, strumming a guitar from one nursing home or assisted living facility to the next, singing nostalgic favorites for residents. He began the sing-a-longs years ago to help his mother-in-law suffering from Alzheimer’s, and after her passing he kept it up. “I do it now because I know that music reaches people,” he says. “Even though my mother-in-law couldn’t talk after a few years of Alzheimer’s, she could still hum along. At adult daycare places I bring sheet music, they pass it around, and we sing.”

Koenigs’ Other Career

Bernie Koenigs attended an Eagle Lake town meeting in 1967 and asked about specific city clerk business that had not been completed. The councilman shot right back, “Can you do any better?” Three days later the councilman knocked at Bernie’s door and asked him to accept two city jobs; that of city clerk and building inspector. Bernie felt he could use the extra income in putting his children through Catholic school. Judy became the deputy city clerk.

“I liked the building inspector job,” he says, “because I could be around people. I got to know all the area builders, and enjoyed watching buildings being built step by step. One night I was inspecting a building with a flashlight. It was easier that way in order to make sure all the nails were in a line and driven into the studs, not just into plywood. Nails shine in the dark, and are much easier to see. All of a sudden cold steel touched the back of my neck. A voice said, ‘Hold it right there.’ I turned very slowly. It was the town policeman. ‘It’s me, Dave,’ I said. ‘What are you doing here this time of night?’ ‘I’m inspecting a house.’ ‘We have thieves in this neighborhood.’ ‘Well, it’s not me.'” In 1978 Bernie quit the city clerk job to spend more time with his family, but kept on as building inspector until 1985.

© 2001 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Bernie, a very nice article about you and your career. Always enjoyed going to you and then it was Richard in N Mankato. Please say hello for me. Galen Nicks Mesa, Az