Katolight Corp.

Photo by Jeff Silker

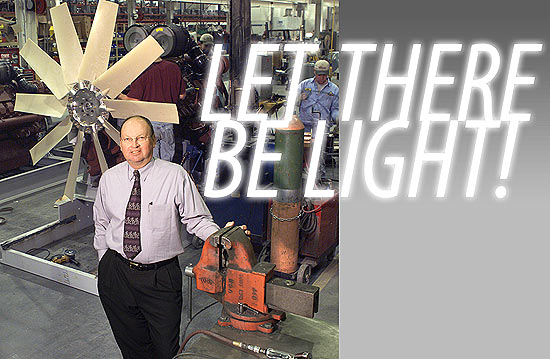

Despite his training as an aeronautical engineer, Lyle Jacobson never designed soaring rockets or jet aircraft for a living. Instead, he discovered life (and opportunities) outside the realm of space.

For 24 years, he’s helped provide peace of mind to people whose feet are rooted firmly on earth, not in the stratosphere. Jacobson heads Mankato’s Katolight Corp., which supplies emergency power generation systems to customers who must continue operating despite rolling blackouts or ice storms.

These customers include hospitals, nursing homes, apartment complexes with elevators and emergency lighting, data processing centers, telecommunications companies, wastewater treatment plants and other industries. Such sales bring in 70 percent of Katolight’s $50 million in annual revenues. Katolight’s agricultural division accounts for another 25 percent. Farms have “critical needs for power,” Jacobson said, especially if they have dairy herds or confinement buildings for hogs or poultry. And there’s an emerging residential market as homeowners begin to fret about the dependability of their electric utility. “Y2K made a lot of people think about the possibility of losing power,” Jacobson said.

Katolight creates emergency power generation systems, matching various engines with generators, then adding the necessary wiring and controls. Marathon Electric, Wausau, Wisc., manufactures nearly all the generators, which Katolight connects to engines made by Cummins, Detroit Diesel, General Motors, John Deere, Mitsubishi and Volvo. (Some of the engines have enough muscle to power trucks or four-wheel-drive tractors.) Company technicians build electronic controls and switching gears for the matched units to create a unified system that’s ready to be wired into a customer’s site. Steel-paneled, sound-insulated cabinets are built around some of the generator sets, known in the industry as “gensets.”

The company produces gensets ranging from 5-kilowatt (big enough to run your furnace and keep a few lights on) to 2,000-kilowatt (big enough to run a small factory). Most are sold in the U.S. or Canada, but there have been some impressive foreign sales. Katolight systems provide backup power for the Beijing newspaper in China and Telesat-Satellite Communications in Macau. In the U.S., Katolight protects the power supplies on the doors of Air Force One’s hangar, the large cranes at Cape Canaveral in Florida and in the State Dept. building in Washington, D.C.

Overhead cranes snake through Katolight’s plant, available to shuttle the largest units through assembly and wiring stages, then into bays where the engines spring to life so the systems can be rigorously tested. Once a unit clears testing, it goes to a massive paint booth so spacious that Jacobson said “you could paint a motor home in it.” Painters attired in protective clothing, wearing hooded breathing units, spray smooth coats of beige on many of the units. “Katolight’s trademark color used to be gold, but when gensets are for outside installation, beige is more environmentally friendly. “We use beige because it blends into the surroundings,” Jacobson said.

There’s plenty of elbow room for all this activity. In January of 2002, Katolight marked its fiftieth anniversary year by moving into a new Mankato industrial park facility. For years the company struggled with cramped, outmoded facilities, eventually finding it necessary to lease outside manufacturing space and run two shifts to keep pace with demand.

Now all 145 employees are on the day shift, working in a plant with 58,000 square feet for manufacturing (28,000 more than before) and another 25,000 devoted to administration, sales and engineering offices. “We figure we can do three times our current volume because of the way the building is designed, operating only on one shift,” Jacobson said. “These concrete tip-up buildings don’t look very expandable, but they are. It’s designed so the walls can be moved out and we can add one or two more bays. The office can be expanded too.” (If demand should ever expand beyond expectations, Jacobson points out that Katolight still owns its former facilities and left some of its cranes and testing equipment in place.)

These days, dealing with growth isn’t a front-burner priority as it was during the 1990s when sales clicked ahead at rates of 15 to 20 percent annually. “The economic downturn, especially in telecommunications, has caused us to regroup. Our sales will be lower this year than last, but we think it’s a transition year and we’ll be back on track in 2003,” Jacobson said.

“The telecommunications business was very active for us up until about a year ago. That’s really dropped off now. They were expanding when stock prices were high and things were booming. They were all scrambling for market share, adding new buildings and every building needed an emergency generator,” Jacobson said. Those generators were often two-megawatt units, selling for about $250,000 each. “As the market dropped and the price of their stock fell, they lost their leveraged buying power and cut way back on capital expenditures.”

Not all segments of Katolight’s market suffered equally in the slowdown. The erosion of telecommunications customers pushed 2002 industrial division sales below 2001, but that didn’t happen in the agricultural division, where demand remained relatively stable.

“Part of our strategy has been to operate in as many markets as we can and to expand geographically. By having an industrial division and an agricultural division, we’ve insulated ourselves somewhat,” Jacobson said.

Katolight’s first customers were farmers, many of them dairymen, who bought small generators known as “light plants” from which the company drew its name. “We still build something called a PTO generator. It can be mounted on a trailer and run from a tractor’s power take-off unit,” Jacobson said. “We’re one of the few manufacturers who still make that product and it’s worth about $60,000 to $100,000 in revenue each month. The PTO generator was our biggest seller in the year before Y2K. We sold $12 million of that unit, way beyond what we’d ordinarily sell.” Katolight’s total sales that year soared to $60 million, thanks to Y2K concerns.

Jacobson believes one of Katolight’s basic strengths lies in maintaining separate sales forces for its industrial and agricultural divisions. “Our ag people really understand agriculture,” Jacobson said. “More and more farms are going to complete automatic packages now rather than portable PTO units. The farms are wired into a permanent generator that comes on automatically,” he said.

In some instances, Katolight’s ag personnel sell directly to farmers or to the manufacturers of farm buildings as well as to distributors. They’ve also developed relationships with large companies that contract with individual farmers to produce poultry or hogs. When these companies require farmers to put up confinement buildings, “it helps when your gensets are recommended by a major organization like Pilgrim’s Pride or Tyson Foods,” Jacobson said.

Katolight continually strives to differentiate itself from competitors. “We’re unique from some of our competitors because we can build a very specialized unit or provide standard sets in all size ranges,” Jacobson said.

Another distinction is the “overall technical support that we offer customers, the ‘after-the-sale’ support.” Katolight maintains a 24-hour telephone service for customers. “Typically we have one or two people on call, but during an ice storm, the whole department might come in or be available on their cell phones,” he said.

Although Katolight sells via distributors throughout the U.S. and Canada, service from Katolight factory personnel is limited to a 150-mile radius around Mankato. Beyond that range, it’s up to the distributors. “We require that our distributors provide service and we set standards for them. We have service support and training sessions here for their personnel.”

Jacobson also sees Katolight’s multiple engine choices as an advantage over competitors who provide only one brand. “Each of our engine manufacturers has different niches in sizes where they’re more competitive. This helps us to better meet a customer’s needs and be more competitive in our pricing,” he said.

A key part of Katolight’s long-range plan is to expand and improve its network of distributors. “We have about 50 distributors now and it’s a continual improvement process. We’re getting about 80 percent of our sales through half of our distributors, so part of our strategy is to help upgrade the distribution network we have,” Jacobson said.

Until now, Katolight’s plans never included a concerted effort to develop business in Mexico or South America. “We’ve dabbled a little in South America and we have distributors in the Caribbean but we’ve been hesitant to move ahead because we didn’t have anyone who spoke Spanish fluently,” Jacobson said. That changed recently when Jacobson learned about a Bethany College student from Chile who wanted to gain some business experience in the U.S. The student, Chris Stange, obtained a mechanical engineering degree in Chile and is working on a business degree at Bethany.

Katolight hired Stange as an intern to research potential distributors in Chile, Venezuela and other South American countries. “It wasn’t in our strategic plan, but it was an opportunity that presented itself and we jumped on it,” Jacobson said. “There’s a large market for generators in South America because utility power there is very unreliable.”

This step toward globalization may offer one route out of 2002’s economic doldrums for Katolight. Another promising path may be the developing residential market for generators in what Jacobson describes as “high-end homes.” That market began to surface in 1999 as Y2K approached, but Katolight didn’t introduce its residential products until the start of 2000. Although Y2K turned out to be a “non-issue,” according to Jacobson, the interest in residential power persists. Katolight’s entry-level residential product is a 9-kilowatt generator costing about $3,000. “It provides enough backup power to handle a well, a furnace, the freezer and refrigerator, your computer and enough lights to get you through,” he said.

Katolight is beginning to introduce more powerful residential packages because “a number of companies are already competing in the 5- to 10-kilowatt range. That’s not our specialty. Too many people can go to Home Depot and buy a 10-kilowatt generator, so we’re aiming at 15 kilowatts and higher. That will run a pretty big home,” he said.

Even after nearly a quarter of a century at Katolight, Jacobson still relishes his job. “When things were booming, I was anxious to get in here each morning and see what we could do to keep things going, implementing new products, finding new distributors,” he said. Given current economic conditions, “the challenge is different, a little more stressful, but still a challenge in finding out how we can grow and do a better job than all of our competitors.” To Jacobson, that means both “being more innovative and recruiting some of the distributors who are unhappy with our competitors, bringing them over to our side.”

Jacobson said he “gets a real kick out of bringing in potential customers or new distributors and showing them our new facilities, introducing them to our employees. I think we have a real upbeat attitude around here with the new building and the way we’re currently operating.”

He said such visits often change the perceptions customers and distributors have about Katolight. “They find we’re bigger than they thought. They’re amazed at the flexibility we have and at some of the sales tools we offer. We have software to help distributors and sales engineers sell and price our products,” he said. Katolight’s interactive tutorials also help engineers determine what size generator is needed for a particular application.

In sizing up its own power needs, Katolight management decided to protect its plant and office with a 900-kilowatt system. It’s large enough to keep the company operating when Excel Energy needs to “shed load” during peak periods. “A lot of utilities offer incentives if you’ll go off-line during peak periods. With Excel, we get a lower rate on electricity all year. In return, they call us five to 10 times during the hottest days of summer and we power up our own generator,” Jacobson said. “You can economically justify a system like this with about a five-year payback. At the same time, you have an emergency generator. It’s an emerging market.”

Jacobson describes construction of the new plant as a “new adventure for us. We had no experience in building a new building, but knew we had to do it.” He relied on his standard management approach of turning good people loose on the task. “We had to pull together knowledgeable people” to work with architects, contractors and vendors. In that group, he particularly credits Bruce Prange, director of manufacturing, and Jim Pockrandt, information systems and accounting manager.

“Prange knew the shortcomings of the old plant from a manufacturing standpoint. He knew what was missing. Pockrandt did a lot of work with vendors supplying communications systems, the phones and computers, to get all that design work done,” Jacobson said.

“Probably the biggest single thing I did to help was to hire Luther Krepsteckies, who’s known as an ‘owner’s advocate.’ He’d been involved in construction of the Midwest Wireless Convention Center, the Taylor Center at MSU and the Andreas building,” Jacobson said. “He became my overall building project manager, overseeing the whole operation, working with the architect, making sure we were getting the best bid prices. He was my right-hand man through the whole building process.”

While the construction project was definitely utilitarian, a lot of attention went to aesthetics, inside and out. “My wife and I are both interested in landscaping so we wanted to make sure the outside appearance was pleasing. We put quite a bit into shrubs and trees,” Jacobson said. “My wife was heavily involved in all the interior design of the office building, helped select the color schemes, the decorating and the furniture. It came a real family project,” he said.

Keeping Up With The Joneses

Katolight Corporation has been a steady employer in Mankato for half a century. It is one of three companies founded by the late Cecil Jones, a pioneer Mankato industrialist. Jones was the father-in-law of Lyle Jacobson, who heads Katolight today as president and CEO.

In 1929, Jones launched Kato Engineering as a manufacturer of generators, then spun off Katolight in 1952 to package generators and engines into emergency power systems. He also started Jones Metal Products. After Jones died in 1976, the family decided to sell Kato Engineering but keep the other two companies. Jacobson and his wife, Kay, are now the sole owners of Katolight, while Jones Metal Products is owned by Kay’s sister, Marcia, and her husband, Tom Richards.

When Jones died, Jacobson was well into a promising career 80 miles away with IBM in Rochester. A native of Duluth, he’d finished his aeronautical engineering degree at the Univ. of Minnesota, then stayed on to obtain a Masters in mechanical engineering. He interviewed with such aerospace giants as Boeing, General Electric, and Pratt and Whitney, but decided to “stay closer to home” and opted for IBM’s offer in 1965. “I was still interested in airplanes and space, but IBM looked like a pretty good company,” he said.

“Those were real boom years for IBM,” he said. His first job involved developing software for mechanical engineers, but within 18 months his responsibilities began to expand. He managed various development departments and a software development group, acquiring skills that eventually became a good “fit’ at Katolight.

Chuck Pennington, a brother-in-law of Cecil Jones and an uncle of Kay Jacobson, headed Katolight at the time. “He was getting into his 60s and didn’t have a successor. He had no children, so the family started talking to Kay and me about considering coming to work at Katolight,” Jacobson said. They had some reluctance about getting into the family business. “Part of our reservation was that Katolight was struggling a little bit in the late ‘70s. Economic times were tight, like now, and inflation was causing a big problem with pricing. There were big increases from suppliers and high interest rates,” Jacobson recalled. “The sales group wasn’t too aggressive, as was common in business in those days. They often waited for orders rather than aggressively seeking new markets and distributors.”

Despite the couple’s concerns, Jacobson left IBM and reported for work at Katolight in January 1979, bringing along his skills with computers, software development and general management. The company then had 45 employees and sales under $6 million. “We went through some interesting times in the 1980s. There were no computers in Katolight, just calculators. The payroll was done manually,” he said. “I came over as a young guy who knew computers and wanted to computerize the company. That was a real test of human relations skills. We had a few old-timers who didn’t think we needed computers. It was a matter of gradually making the internal changes.”

Looking back, Jacobson feels his “management training at IBM was most beneficial. The technical aspects of the product weren’t a problem, although I still don’t consider myself an expert in generator sets. I haven’t had to do any design work.” Instead, he “concentrated on general management skills and hired good people to do the technical work.”

In 1986, Jacobson became president and CEO when Pennington retired. (Pennington, now 89, maintains an active interest in the company and still comes to the office every day. That’s an example the 61-year-old Jacobson hopes to follow.)

“We have a very good management team, one we’re proud of. That allows me to start going on vacation a little more. I can be gone several weeks and things still run smoothly,” Jacobson said. “None of our children is involved in the business, so when we talk about where we’re going in the future, I think my goal is to be involved to some extent but not as actively as in the past. When I’m 89, I’d still like to have an office here.”

Jacobson makes no effort to disguise the pride he’s developed in Katolight since January 1979, when he had reservations about moving to Mankato. “We’ve got an excellent company, my wife and I are proud of our employees, there’s a really good work ethic in the company, and we want Katolight to continue to be a good member of the Mankato area community,” he said.

Hickory Street Optimism

These are “exciting times” for HickoryTech, the regional communications powerhouse that grew out of the old Mankato Citizens Telephone Co., according to Lyle Jacobson.

Jacobson, who is president and CEO of Katolight Corp., has been on the HickoryTech board since 1987. “It’s really exciting, challenging and fun to be involved in that,” he said. Despite an economic downturn that’s been particularly hard on technology companies, Jacobson said HickoryTech “still is a profitable telecommunications company doing quite well. “Its stock has held up relatively well, going from $16 or $17 a share to $11, while other telecommunications stock went from $100 to nothing,” Jacobson said.

“The challenge is how to keep it growing in the rapidly changing telecommunications business with all the big companies competing in areas like wireless. The wireless part and how to increase its profitability is one of our biggest concerns,” he said. “All of the large national companies are offering free long distance service, but we have towers only in Southern Minnesota and Iowa. We’re looking at special marketing programs so we can carve out a niche.”

Although Worldcom went bankrupt owing HickoryTech about $1 million, Jacobson said it’s important to keep the loss in perspective. “It hurt, but it really wasn’t that significant for a company with more than $100 million in revenues—and some of it may be recoverable,” he said.

© 2003 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.