Mankato Symphony Orchestra

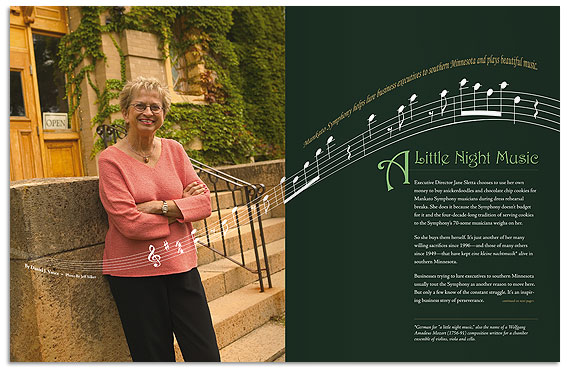

Mankato Symphony helps lure business executives to southern Minnesota and plays beautiful music.

Photo by Jeff Silker

Executive Director Jane Sletta chooses to use her own money to buy snickerdoodles and chocolate chip cookies for Mankato Symphony musicians during dress rehearsal breaks. She does it because the Symphony doesn’t budget for it and the four-decade-long tradition of serving cookies to the Symphony’s 70-some musicians weighs on her.

So she buys them herself. It’s just another of her many willing sacrifices since 1996—and those of many others since 1949—that have kept eine kleine nachtmusik* alive in southern Minnesota.

Businesses trying to lure executives to southern Minnesota usually tout the Symphony as another reason to move here. But only a few know of the constant struggle. It’s an inspiring business story of perseverance.

For one, most business people would be impressed with the Symphony’s knack for hiring experienced “labor” for the equivalent of peanuts. “Our musicians get an honorarium,” says Sletta from the Symphony’s Broad Street office. “Regular session players earn $17 for a rehearsal or concert, and the string principals $21 for a rehearsal and $22 for a concert. Musicians from outside Mankato receive 18 cents a mile for driving expenses. It may not seem like a lot, but when you multiply it by 80 that’s a lot of money to our budget. And obviously, these people play for the love of playing.”

In fact, the Symphony’s shoestring budget has become sort of a running joke with musicians. One string bass player asked Sletta last spring, “When are you going to buy me a cushion for my stool?” and others have kidded about receiving reserved parking spots.

One “typical” performer is Arnold Krueger, a retired music teacher from Owatonna High School, now living in Le Center. Krueger, in his 70s, plays first violin and is “a great player,” says Sletta. “And he wants to continue playing.” Other musicians are high school or private instructors, or college professors, such as John Lindberg of Minnesota State and Ann Pesavento of Gustavus Adolphus. There’s an electrician, a doctor and many other occupations represented—some even play in rock bands.

Conductor Dianne Pope recently hired a substitute bassoonist who had moved to Hutchinson from out of state for a job totally unrelated to music. He discovered the Mankato Symphony over the Internet. Sletta says he’s an “outstanding” player and would have been hired as a “regular” if it hadn’t been for the Symphony already employing two bassoonists.

“The majority of our musicians live in Mankato,” she says, glancing down at a sheet of paper on her desk. “Last year 32 came from Greater Mankato, ten from St. Peter, six from Minneapolis, five each from New Ulm and Northfield, three each from Faribault and Albert Lea, and others from Blue Earth, Shakopee, Madelia, Lake Crystal, Lester Prairie and Welcome.”

New musicians can’t just walk on; they must audition with Pope every year around Labor Day. “Once people are in the orchestra, though, they don’t have to re-audition annually,” says Sletta. “But after dropping out a year, they must re-audition. The standards are higher today. Dianne really challenges them artistically and has brought them to a higher quality level. I can tell the difference over the last eight years.”

In September 2004, about 15 musicians auditioned for positions. Of the six chosen, four were exceptional area high school students and one a college student. Depending on the piece performed, the Symphony uses between 70 and 80 players for any given concert.

“We have a lot of high school kids auditioning,” she says, a tinge of excitement in her voice, “and you’d be surprised at the number of home-schooled children participating in and winning our Young Artist’s Competition. Our judges coming in from outside the area are amazed at how well all the students do.”

In an age of constantly changing pop music tastes, the Symphony is trying to market an established product that traditionally has appealed, for the most part, to people over age 50. So it wants to branch out to a younger audience. However, competition for the younger entertainment dollar is fierce: Midwest Wireless Civic Center and MSU concerts, bars, special events such as Ribfest, recorded music, and on and on. Marketing to younger generations, the Symphony recently used a $10,000 “Statewide Audience Development Initiative” grant from the state government to promote season ticket sales at this year’s free “Rockin’ in the Quarry” concert.

The quarry concert itself has been a “reaching out” marketing tool. Begun 1999 to mark the Symphony’s 50th anniversary, it has blossomed into a major regional event that successfully attracts the Symphony’s target audiences of students and younger families. “We wanted a free concert to say thank you to Mankato for supporting us,” says Sletta of the first quarry concert. “Initially, someone we’d asked to underwrite it turned us down. So I approached Symphony board member Dick Lundin and asked if Southern Minnesota Construction would consider underwriting. SMC agreed and asked if we could hold the concert in one of its rock quarries. We were willing to try anything if they were willing to underwrite.”

The first concert was a “god-send” for marketing to a broader audience, says Sletta. The next year the Symphony began hosting a fundraising gala at the quarry the night before the concert. “We’ve lucked out on weather except for one year when a downpour hurt the results at the gala party and another year when it was extremely windy the day of the concert,” she says. “Because of the dust and humidity, we encourage musicians to use older instruments for the quarry concert, not their best.” The Symphony performs inside a special tent that funnels the classical sound out and into the audience. Even yet, the uncooperative quarry acoustics and occasional brisk wind require the use of a number of microphones and speakers.

To market the Symphony year long, “we do a lot of bartering,” says Sletta. “And we have a fund drive. This year we had 15 people making personal calls on people targeted as possible large donors and we had good results. So this next year we’re expanding on it.”

Ticket sales generate only 17 percent of the Symphony’s $213,000 budget; the rest comes from a hodge-podge of state money, the quarry gala, the fund drive, grants, concert sponsorships, contributions, and a season opening fundraiser hosted by the Symphony Guild. The Symphony reduces marketing costs by bartering and receiving in-kind gifts, such as free graphic design services from Kris Higgenbotham.

But the greatest marketing challenge by far and “the $1,000 question,” as Sletta puts it, is in steering even more of the hip-hop and rock generation toward Berlioz and Bach. “Youth education is in our mission statement and it’s our future,” says Sletta. “The four main components of our efforts in outreach education are the Young Artists’ Competition; Young Composer Contest; annual youth concerts; and Music Appreciation at the Elementary School Level (MAESL), which fosters in elementary school children an appreciation and curiosity about different musical instruments.”

One day each May orchestra members take vacation time from their day jobs to perform three concerts in succession at Mankato West to a total of 3,000 fourth through sixth graders. “Dianne Pope really makes this event educational,” says Sletta.

And she can’t say enough about Conductor Pope. “It’s her 22nd year in Mankato and we are very fortunate to have her. She has established herself as an outstanding conductor.”

*German for “a little night music,” also the name of a Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91) composition written for a chamber ensemble of violins, viola and cello.

Executive Director Needs Bach-up

Besides paying for dress rehearsal cookies, Executive Director Jane Sletta helps keep the Mankato Symphony in tune by organizing volunteers for various tasks. But that hasn’t been easy. “When my children were young, women didn’t work outside the home,” says Sletta, 68, from her Broad Street office, referring to the mostly female and all-volunteer Symphony Guild. “Many women active in the past as Guild officers didn’t work outside the home and could devote more time to helping. When I started in 1996, Carol Alton was Guild president and she was very successful organizing the Guild to carry out various projects, such as fundraising. But now many younger women work and when they come home they need to spend time with family.” Symphony Guild members now often volunteer on one project annually, such as fundraising, MAESL or ticket sales.

To organize a Guild of younger, working members—it used to be organized by a volunteer president—the Symphony a year ago hired a part-time paid “coordinator.” But after a few months and a better job offer she left. That same week the state arts board notified the Symphony that $10,000 would be cut from its annual contribution. With that cut, the Symphony couldn’t afford a replacement—so Sletta picked up the slack in addition to other duties.

She has a passel of other challenges, including placing the Symphony’s 566 season ticket holders in the right seats. “When getting a seat location they like, they can keep it for the next year if they renew by May 31,” she says. “If they don’t, they lose them. Often I get on the phone to remind people.” Season tickets run about $60 per person for five concerts.

Plucking two note cards off her desk, she adds, “And this year I received two cards in particular from people I called to remind about renewing. The first says, ‘Dear Jane, I am so sorry to have been so forgetful. I have no excuse except for age, I guess. Anyway, we appreciate you taking care of us on this matter.’ The other card said, ‘Thank you for reminding Gladys to reorder tickets.’”

Cookie Break!

One important job is providing cookies for orchestra members on rehearsal nights. The Symphony Guild has been doing this for years, probably since the guild began in 1965. The women then said they wanted to do something nice for orchestra members.

So our rehearsals run from 7:00-9:30 at night and at about 8:15 they break. That’s when the Symphony Guild brings the musicians cookies. If someone forgets them, I hear about it. Now I have one woman and that’s all she does is deliver the cookies. She’s the cookie lady.

The Guild doesn’t provide cookies for the Saturday dress rehearsal, however. So now I buy cookies for that and bring coffee and orange juice. My husband says I’m mothering them. —Jane Sletta

Sletta Sings Her Operetta

Mankato Symphony’s Jane Sletta was raised on a dairy farm near Adams, Minn., southeast of Austin. Active in 4-H, she often showed animals at county fair. “My brothers were good at dairy farming,” she says. “I did learn to drive a tractor and a car out in the fields, but milking cows wasn’t for me. So I went into sewing and cooking and ended up at St. Olaf College earning a bachelor’s degree in home economics education. I was planning on being a home economics teacher.” She graduated from St. Olaf in 1958.

She continues, “Then I learned of an opening for a county home extension agent in Blue Earth County. I worked for Blue Earth County and part of my paycheck came from the Univ. of Minnesota because I was considered a University instructor. In essence, I was a county home economist.

“In those days women married right out of college and most of my friends were married. For whatever reason, I said to myself that if not finding a man in three years I’d find another job elsewhere. Now isn’t that ridiculous? Anyway, I joined the church choir and there he was, Con. We married in 1960 when I was 24.”

Sletta was a county home extension agent four years before having children. “In those days you stayed home while raising your children,” she says. “I didn’t return to work until my girls were in junior high and by then the home agent positions were filled. There were not a lot of positions for home economists in the mid-’70s. So I worked in retail.”

Her new career began at the Emerald Cuckoo Gift Shop. She went on to manage Jim Carroll’s Cheese Chalet for a short time and then worked at Fawbush’s and Kristine, both women’s apparel stores—then on to the Mankato Civic Center as a catering consultant, helping plan wedding receptions and special events for Najwa Massad.

“From there (in 1996) someone active in the Mankato Symphony told me they needed a new manager,” she said. “I was offered the position, at the time thinking it would make a nice part-time job. I’m interested in music. Little did I know it would grow to a more than full-time job, which my husband will attest to when we do bulk mailings together.” —Dianne Pope, Conductor

On The Symphony

I love the town and the people in the orchestra. They make great music and are fantastic musicians. —D.P.

On Being Hired

I was 39 when seeing a notice for a conductor and sending Mankato a resume. I heard they received over a 100 resumes from all over the world. I made it through a telephone interview and ultimately went there along with four other candidates to conduct the orchestra one evening at rehearsal. We each had 30 minutes.

If I remember correctly, they offered me the position that night. My husband was there with me and wore a bouquet of flowers. The board president asked my husband what the flowers were for and he replied, “They are to congratulate her if she gets the job, and to make her feel better if she doesn’t.” I was excited, very excited. —D.P.

On Her Background

Before joining the Mankato Symphony I was assistant conductor of the Des Moines Symphony and had formed a chamber orchestra in Vienna, Austria. I grew up on a farm near Onawa, Iowa, earned my Bachelors from Drake Univ. and Masters from Kent State. Then I took advanced conducting instruction at the Academy of Music in Vienna. —D.P.

On Staying In Mankato

I’m 61, but conductors usually go on a long time. I guess we have good upper-body strength from waving our arms around a lot. —D.P.

Her Favorite Music

Anything by Brahms. There is something about his music that speaks to me. —D.P.

© 2004 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.