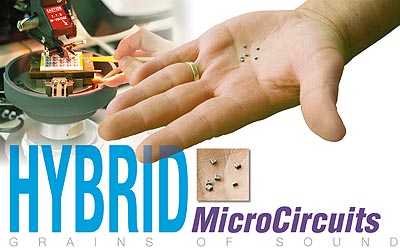

Hybrid Microcircuits

Tim Mullen dreamed of starting his own business for years, but never once fantasized about building the world’s smallest hearing-aid amplifier. Now he’s done both.

In December of 1991, Mullen and three like-minded partners put their new company together on paper, incorporating as Hybrid MicroCircuits, Inc.. In February of 1992, they opened their doors in Belle Plaine, long on experience but a tad short on capital and pinched for space. In 1993, they alleviated their capital and space situations by moving 110 miles south on Hwy. 169 to Blue Earth.

Hybrid MicroCircuits now has 32 employees specializing in building tiny amplifiers for hearing aids. It’s about to broaden this product line and, Mullen hopes, double its sales next year. He and his partners uncovered their current niche while researching the kind of business they might start.

“We wanted something we were familiar with and we wanted something that’s environmentally friendly,” Mullen said. Since the four men have more than a century of experience between them in manufacturing electronic components in the Twin Cities, they naturally leaned in that direction. “This kind of business is very friendly to ecology, very clean, with very few pollutants,” Mullen said. “Our production area is so clean you could almost perform surgery there.” Most of the assembly and wire-bonding is done with precision equipment under 70-power microscopes.

But exactly what kind of electronic components to manufacture? In probing for products, they discovered considerable discontent among the makers of hearing aids. “They were complaining that nobody was helping them or paying any attention to them because their market was too small,” Mullen said. “They weren’t getting the engineering and design help they needed on components and their shipments were behind schedule from suppliers, who were concentrating on customers with larger, higher volumes.”

The partners recognized this opportunity to slide into a niche and decided to specialize in producing amplifiers for hearing aid manufacturers, figuring they might achieve $2 million in sales within five years. (They’re at $1.8 million now.) “Most hearing aid companies, except for the really large ones, can’t afford to have an operation like ours in-house, just to suit their needs. It wouldn’t pay off,” Mullen said. “It costs too much… the technical expertise, the equipment, new techniques.”

Mullen credits one of the partners, Bob Geib, with getting HyBrid MicroCircuits’ first orders from hearing aid manufacturers. “Bob has been affiliated with hearing aid people for 48 years. He had the contacts.”

Besides Geib and Mullen, the other partners are Steve Meyer and Willard Laabs. In 1968, Geib founded HEI, Inc., in the Twin Cities and retired from that company several years ago. Mullen, Meyer and Laabs all worked for Geib at one time or another. “HEI is a custom job shop, a hybrid house, for manufacturing electronic components. A hybrid house “hybridizes” components, taking a printed circuit board that’s four by six inches and shrinking it to one by two inches, using different technologies,” Mullen said. “Our business comes when somebody wants to put a two-pound package in a one-pound container. We know how to shrink it down. This type of product is becoming more and more in demand because it’s low in power consumption, creates less heat and takes less space.”

Geib, 73, serves as the engineer for Hybrid MicroCircuits, using CAD (computer-aided design) software at his home in Minnetrista, a Minneapolis suburb. Now that the company has a long list of established accounts, he’s given up his sales role. “He sits at his computer and uses CAD (computer-aided design) software. He keeps designing this stuff smaller and harder to make,” Mullen said. “He gives me fits.”

Meyer, 51, is the company’s manufacturing expert while Laabs, 59, specializes in the ceramics to which gold wire, thinner than a human hair, is bonded to form intricate circuits. Mullen, 58, describes himself as “a mutt, a half-breed. I don’t do any wiring. If I try to fix things at home, there are earthquakes,” he said. “I’m president, CEO, general manager and janitor. I do the planning, the budgets, the managing.”

Right now, Mullen also doubles as quality assurance manager since the one they hired for their rural plant decided to return to life in the Twin Cities. It’s not a responsibility Mullen puts on the back burner, because Hybrid MicroCircuits is in the process of becoming ISO 9002-certified and tests 100 percent of the parts it produces twice a pre-test and a final test. “Our reject rate from the floor is about 4 percent, and our returns from the field are only about 3/10ths of one percent,” Mullen said.

The company has added a salesperson “to get us into other markets beyond hearing aids,” which is necessary if sales are going to double next year. The expansion has already started. “We’re building a prototype for a communications product and we’re doing resistor networks for a nationally known electronics manufacturer,” Mullen said. And there’s still plenty of growth potential in the hearing aid business, according to Mullen. “Part of it is because of our aging population, part of it is from hearing damage suffered from loud electronic music or machinery,” Mullen said. Another factor is foreign sales. “Most foreign countries used behind-the-ear hearing aids, but now they’re going toward the smaller and more sophisticated apparatuses which fit in the ear canal, which is where we specialize,” he said. When the company started, the hearing aid industry was experiencing 3 to 4 percent annual growth. “This year it’s 10 percent,” Mullen said.

As is typical in the component industry, manufacturers often don’t know exactly how their piece fits in the customer’s final product, or even what the final product might be. That was the case in 1996 when a company furnished Hybrid MicroCircuits with the schematics for a pre-amplifier. The finished size was so small (0.080 by 0.075 inches) that the project tested Geib’s engineering expertise and required special tooling for the ceramics by Laabs.

“We didn’t discover that we’d built the world’s smallest hearing aid amplifier until about a year later when Siemens, the largest hearing aid manufacturer in the world, told us they had it in one of their inner-ear models,” Mullen said. “I was surprised, but Siemens was shocked when they learned we’d built it. We’d done it for a sister company of theirs, and they’d been buying it from that company.”

Mullen said other component makers have since duplicated the amplifier’s size, “but to my knowledge, there are none smaller. When we got into the amplifier business, people said we weren’t conforming to design rules and that’s probably true, but we were making it work. Those people either had to come up to our design rules or get out of the business.”

Hybrid MicroCircuits’ production runs range from 25 parts to 4,000, with most in a range between 250 and 1,000. When the company broadens its product mix, Mullen expects to encounter high volume runs, perhaps as many as 50,000 parts per week. That kind of volume generally winds up being farmed out to plants in Mexico or Malaysia, but Mullen believes U.S. companies can be more competitive than most people think. Rather than look abroad, Mullen plans to set up a high-run operation in the Blue Earth Industrial Park. Communications with a foreign subsidiary are costly, there are problems with engineering and processes and the equipment that’s required costs the same (except for the monetary exchange rate) whether it’s installed in Mexico or Blue Earth, according to Mullen. Foreign labor costs are also going up. “People don’t want to work for pennies anymore. They want the same things we want,” he said.

Mullen said his present operators can average 400 wire bonds an hour. “When we eventually encounter the high-run stuff, we can bring in a machine that will do 6,000 bonds an hour and set up a special operation in our own industrial park,” he said.

After nearly four decades of working for various companies in the Twin Cities, Mullen seems to have developed a special affinity for his new locale. His relationship with Blue Earth began in 1993, when HyBrid MicroCircuits decided it needed more operating capital and more than 1,000 square feet of rented space in Belle Plaine to survive. It also wanted a more favorable labor market than exists in the Twin Cities. Blue Earth (Population: 3,745) became one of seven rural communities competing to attract the brand-new industry.

Mullen said Blue Earth’s biggest advantage was the facility it had to offer: 10,400 square feet in a mall along Hwy. 169, which could be rented on an escalating scale starting at a very favorable rate. (The company uses only 7,500 square feet, giving it “elbow room” for the growth Mullen forecasts.) The Blue Earth Economic Development Authority bought $50,000 in Hybrid Micro-Circuits’ preferred stock, while the Faribault County Industrial Redevelopment Agency provided a low-interest $20,000 loan. Pioneer Bank in Elmore helped the company secure additional financing from the Small Business Administration.

While the labor supply in rural areas is traditionally tight, Mullen said Blue Earth has “good people, hard-working people.” To attract them, he knew it would take competitive wages plus fringe benefits like paid holidays, vacations and health, dental and life insurance.

Although it’s not uncommon for entrepreneurs to keep their homes in the Twin Cities and commute to small towns, Hybrid MicroCircuits’ top three executives moved with the company. Mullen and Laabs bought homes in Elmore (Population: 709), just south of Blue Earth, while Meyer found a house in Blue Earth.

“I wouldn’t move back to the Twin Cities…all that traffic, too many people, too much travel time to and from work. It used to take me 45 minutes to get to work in Belle Plaine. Now it’s five minutes,” Mullen said. “I grew up in Walnut Grove (Population: 625) so living in Elmore brings me back to my childhood days.”

It’s not just the short commute and the new surroundings that Mullen enjoys. “I just love doing this, everything about owning my own company, seeing it grow. But you have more responsibility to your employees than I thought,” he said. “I’ve become as deeply concerned about their welfare as I am about mine, because without their help, we can’t get where we’re going.”

©1997 Connect Business Magazine

This depends on the market value of the item at the time that the donation is made.

) from the noise or voice you intend to comprehend.

Intrigued how in spite of being so small, they have

such a long life.