Schmidt’s Bakery

Photo by Jeff Silker

Earlier this morning I’d eaten but one lone bagel, flavored with Smart Balance margarine that contains no sugar and only five fat grams per single serving. I’d purposely starved myself. Two hours later, and now, on the road to my next assignment, I am nearly drooling from being tempted with thought after delicious thought of making taste bud love to a glazed doughnut.

I am motoring towards Sugar Mountain.

Schmidt’s Bakery in St. James really shouldn’t be in business. But for over 75 years it has somehow managed to survive the competition it gets from all those in-store bakeries which are tucked inside all those supermarkets which are part of all those supermarket chains which routinely beat out the little guys. Over the years the chains have cast many an independent meat market, deli, bakery, drug store, and even floral shop into oblivion. Only a few proud holdouts remain.

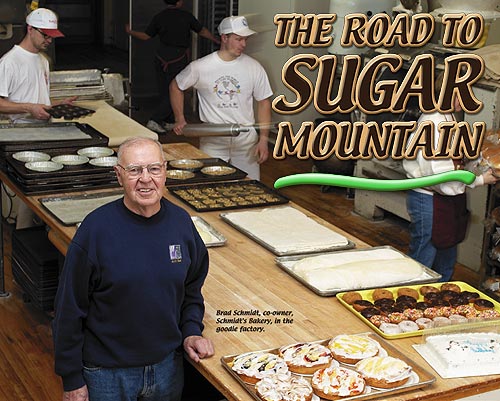

At the rear of the bakery I’m motioned into a cramped office, more a cell, where Brad Schmidt, 69, one of four family owners, begins telling the Schmidt Bakery story. He is one-fourth of a corporate partnership now involving his oldest son, Joe, his brother, Paul, and Paul’s oldest son, Tom. While he talks all I can think about is sinking my teeth into any one of the dozens of doughnuts and pastries gracing the trays to my left.

“My father and uncle started this bakery way back when,” he says.

While he talks I scan the length of a 37-pound lake trout his father caught in 1965, a crucifix, and a “Once I thought I made a mistake but I was mistaken” plaque which all hangs on the wall behind him. He continues on. “My uncle, John, was sent by the U.S. Navy to Dunwoodie Institute during World War I. When he got out of the service he came home to St. James to work in a bakery. When that baker decided to sell in 1923, my uncle and my father, Herman, bought the baker out.”

In the ’20s a bakery could be an uncomfortably hot place. Air conditioning, of course, didn’t exist, and what was a coal oven then had to be fired by hand two hours before baking, with temperature adjustments more guesswork than science. Later, in the ’30s, more modern “stoker” ovens, which were fed coal augured in from a hopper, featured automatic thermostats that better regulated temperatures.

Brad began his bakery career as a ten-year-old helping his uncle and father by filling the coal hopper, washing the dishes — and occasionally cleaning the stoker oven once a month to remove soot. Lard, back then, came in 300-pound oak barrels, and flour in 100-pound sacks. While other St. James boys in the late ’40s were dreaming of college or a career in the military, Brad only wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps. It was all he knew. In the early ’50s he began waking up at 3:30 for the morning shift. About the early hours, he says, “I missed out on a lot of social things because I had to get up so early. With those hours I’d usually sleep two or three hours in the afternoon after work, then stay up until ten that night before falling asleep again.”

Tonight, to fill all the orders, one of his 18 employees must begin baking preparations at midnight and others will have to file in at 2:00, 3:30 and 4:30. At 69 and now semiretired, Brad handles the company book work without the aid of a computer. His older brother, Paul, has been fully retired a while.

As he speaks my left elbow just happens to be resting on a tray brimming with gooey chocolate chip cookies ordered by an area supermarket. I lick my lips. “We received our flour then in hundred pound bags,” he says, pointing with his index finger down towards the basement. “We filled our basement hopper with flour and the hopper would elevate the flour upstairs where it would be dropped into a cone above the mixer.” They survived the Depression, and later the rationing woes of sugar and shortening during World War II.

Their wholesale trade kept them from falling by the wayside, like so many other bakery operations in southern Minnesota that had fallen. Brad explains that most in-store supermarket bakeries today buy frozen doughnuts and rolls, for instance, to thaw out, bake and sell. Of course, these baked goods aren’t nearly as fresh. “But everything we bake here is from scratch,” he says proudly. “We’ve always used quality products and everything we sell is made fresh daily.”

The sight and smell of a fresh birthday cake, not two feet away, iced over and ready-to-go, grabs hold of my eyes and nose.

“Even though both supermarkets in St. James have in-store bakeries, both still buy a full line of fresh products from us wholesale,” says Brad. “The supermarket in Madelia sends a truck every morning to pick up an order called in the night before. A supermarket in Mountain Lake comes five days a week. Other groceries from Odin, Comfrey, LaSalle and Godahl send trucks but not as often. We also deliver to the local hospital, a retirement home, restaurants. We were able to survive the times by becoming a pick-up wholesaler. We don’t have the expense of running a delivery truck. And we make exactly what our customers want.”

Deliveries to out-of-town accounts ended in the ’50s just when so many other bakery wholesalers, four at one time, including Wonder Bread, began direct-store delivery. When Schmidt’s quit delivering stores began picking up product. Schmidt’s delivers now only to St. James accounts. Wholesale customers account for a whopping fifty percent of sales.

I try to drop a not-so-subtle hint. “Brad, do you ever eat what you bake?”

“If I ate everything that looked good to me I’d probably weigh about 400 pounds,” he beams, rubbing his belly. “So many things look so good in this bakery and I just love to eat.” His personal favorites are chocolate doughnuts topped with chocolate icing, and prune danish.

C’mon Brad, catch the hint.

They sell a full bakery line: doughnuts, bread, wedding and birthday cakes, cookies, danish, fancy pastries, hamburger and hot dog buns. Doughnuts and danish are best-sellers. During summer grilling season they bake up to 500 dozen buns for an average Saturday, and 1,000 or so for July Fourth, Memorial Day or Labor Day. On graduation weekend at the local high school they bake 5,000 dozen of a two-third sized hamburger bun. Their full line of baked bread includes fifteen varieties of white and dark. They use four blends of flour — for doughnuts, cakes, bread and cookies — purchased through three wholesalers.

The rear of the bakery has a Triumph ingredient funnel from the ’20s, a modern mixer, a 9-foot high Baxter baking oven, a doughnut fryer, a Reed oven for rising dough, and any number of tray carts packed with baked goodies. Lovely maple wood floors, the envy of any homeowner, are swept clean throughout the day.

About 600 pounds of flour and 150 pounds of sugar are used daily, along with all manner of dried egg and milk powder, jams and jellies, spices, flour from rye to corn meal, all to rehydrate the many mouth-watering recipes handed down from father to son.

“Nearly all the recipes,” says Brad, a gleam in his eye, “are ones my father and uncle used in the ’20s. The fruitcake recipe, for instance, one of the first created, is a pretty good one. We sell almost 400 from Thanksgiving through Christmas. A customer told me the other day, ‘I wish you’d get rid of those fruitcakes. I’m on my ninth one.’”

That does it. These guys can even make fruitcake taste good.

A second later a knock comes at the office door. It’s Jeff Silker, a free-lance photographer, eager to begin shooting the photo you see on page 44. While Brad, Jeff and the crew at Schmidt’s set up, I make my move up front where tarts and turnovers and doughnuts and danish and fresh bread and — Lord, I just can’t take it anymore. I just have to have a sample.

But no retail clerk offers me one.

So I query a waiting customer, “Do you like the food here?”

“I just love this place,” she says as she points towards a mouth-watering cinnamon roll, which just compounds my frustration. She says she has driven in today from Welcome, twenty miles, and that her friend will often drive in from Fairmont. “I am a bit disappointed, though,” she says, “because my personal favorite is French doughnuts and they’re out today.”

I glare down at the doughnut selection, lick my lips. Maybe this will give the two retail clerks on duty the big hint that I’m starved for sugar and must have a free sample right now because I’m writing a story on Schmidts and I didn’t eat much breakfast so I could feast on this! But no such luck.

Shirts, sweatshirts and tee-shirts with the Schmidt’s name hang from one wall like coconut strips off a bundt cake. There’s a framed Star Tribune article that ran about ten years ago. Jeff’s camera lights are flashing in the rear. He’s nearly done setting up. On the way back to Jeff I can’t believe all the baked goods — a selection made possible in 2001, I surmise, by a three generation-old commitment to quality and to a wholesale sales strategy that embraces its supermarket competitors. In the back I say “Cheese!” and all smile. At the end of the photo session, Brad motions me into his office for a wrap-up to the interview.

“Do you have any final words?”

“Well, we’ve been in the same location since 1953. Before that, from 1923-1953, we were down the street.”

“That’s a long time.”

“It sure is.”

I think for a moment, get curious. “What about your personal life since retiring?”

He semiretired about ten years ago, he says. To work off his chocolate doughnut with chocolate icing binges then he began riding his bicycle to help with an annual multiple sclerosis fund-raiser. He personally raises over $1,000. It’s a heartfelt issue: a St. James friend has the disease, and so does his wife’s friend, a Sleepy Eye woman. He also has other bikes, Harleys, which he likes to motor to the River Road Run, another annual multiple sclerosis fund-raiser. One is a 1995 Heritage Classic and the other a 2001 Heritage Classic Springer. He’s been to Sturgis once. “It’s pretty wild,” he said. “Once was enough.”

I’m standing around after the interview, resigned to fate, just praying someone will offer a sample of what has been driving my olfactory absolutely crazy. The aroma is intoxicating. Thank goodness Jeff Silker senses my weak state and asks a Schmidt employee for a sample just two seconds before I would have begun ripping out my hair. From the display case I choose a fresh cinnamon roll, white icing, which the clerk says retails for only twenty-nine cents.

Oh, baby now. Oh to live on Sugar Mountain.

© Copyright 2001 – Connect Business Magazine