American Artstone

Photo by Jeff Silker

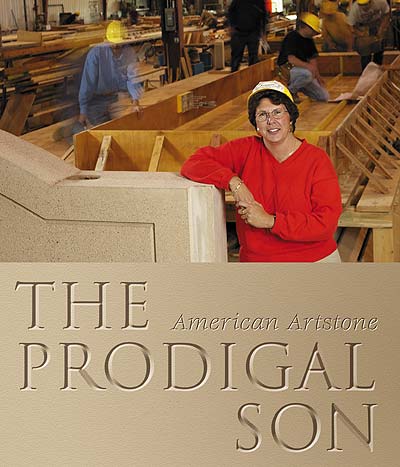

Nancy Fogelberg seems a bit taken aback when people credit her with turning around what was once a prodigal company, New Ulm’s American Artstone, now a $4.5 million, 50-employee, Midwest leader in architectural pre-cast concrete. She gives all the credit for the turnaround to her employees.

Like the biblical Prodigal Son, the company she runs was born of a pedigree, and had all the potential in the world for good, but somehow had lost its way. American Artstone was at rock bottom in late 1992 when Fogelberg received a telephone call from one of its board members. “How would you like to be president of a company again?” the caller asked.

Fogelberg, then 44, up to that point had travelled a long and winding career road. She had taught elementary students in St. Paul Public Schools for 11 years, trained employees for Honeywell and Graco, and marketed Marvin Windows to architects. The board member, however, was referring to her six-year stint as president of Fogelberg Company, which she chose to run after her father died unexpectedly in 1984.

“I stepped in [at Fogelberg Company] as an outsider, and knew a lot about nothing,” she says today from American Artstone offices on North Broadway, across the street from New Ulm trucker J&R Schugel. “I got my ‘M.B.A.’ by the seat of my pants through the world of hard knocks.” Fogelberg Company acted as a sales broker for companies manufacturing construction material in the Upper Midwest.

The board member asked if she had ever heard of American Artstone. “No.”

“Do you know what pre-cast is?” “No,” she said again, “but I do know quite a lot about roofing, siding, glass, wood and louvers.”

Fogelberg promptly telephoned American Artstone and asked them to mail out information on the company, which had been based in New Ulm since 1914. “I never received the information,” she admits. “That was how undisciplined they were. They were like helium balloons on short strings. They needed to be anchored and brought together.”

She drove down from her home in St. Paul the day after Thanksgiving 1992 for a plant tour on a company “off” day. One employee she met was Todd Rademacher, the company accountant. She asked him specifically what he did, and his rattling off a long list of dos and don’ts caused her eyes to gloss over. When he had finished, Fogelberg queried back, “How many hats do you wear at one time?” It seemed like his was an overwhelming job. A week later she drove down again, this time with the plant up and running, to press flesh with other employees and to learn more.

After the interview process, the board asked her to start on February 1, 1993. And on her first day she stood atop a production table to explain her presence to the 30 men glaring up at her. “I’m your new president,” she began, feeling for the right words. “I don’t know concrete, and I don’t know pre-cast. However, I can learn it. But I do know managing and marketing.”

She earned respect by spending quality time in the production plant, mixing and molding mud alongside muscular men while gigantic cranes carrying tons of mix tottered overhead. She learned troweling, finishing, and mixing. Her 11 years of experience teaching in St. Paul had greatly helped her hone her management skills. (She claims “you would be hard pressed to find a better manager than a classroom teacher.”) When production decisions had to be made she stunned frontline workers by actually asking them for their opinions. She knew that any solution ultimately had to be theirs in order to develop a sense of ownership in the company.

The basic production process seemed simple enough for her to understand: buy stone aggregates from suppliers; mix them into a cement base; pour the mix into huge wooden molds; and finish the cured, decorative product before shipping it out on a truck. Contractors and architects were her chief customers.

The company seriously lacked an esprit de corps, so Fogelberg began weekly production meetings in an office so cramped that supervisors had to stand the entire meeting elbow-to-elbow — aligned like bowling pins on an alley — in front of Fogelberg’s desk. “The guys didn’t know what one was at first,” she says, referring to a production meeting. “Our initial meetings weren’t that productive. I would ask questions and usually get an ugh! response back.” Before long supervisors started talking with each other, settling problems, and even setting their own priorities. The Prodigal Son was beginning to head home.

American Artstone had developed a negative reputation in some segments of the construction industry because of one job for a prominent Twin Cities mason in which Artstone shipped “coping” to a site days before sending out the ordered “base panel.” “Apparently, the guys in our plant felt like doing the coping instead,” she says, rolling her eyes. “In construction you work from the bottom up, and we had sent a mason the top piece first and it was absolutely useless to him in that order.”

She still views a business relationship as a partnership, even a marriage, which requires open dialogue between all the affiliated parties for a building project to succeed. Today, general contractors, her main customers, are regularly called and asked such basic questions as: What’s your time frame? Which piece do you want first? Where are you starting on the building?

Their production plant was a “dump.” In late 1993 she hired an engineer to evaluate the physical plant, and armed with “proof” she received her board’s blessings to proceed with new building construction plans. “I had this fear that if we had a large, wet snowfall the whole building could implode,” she says. “I knew when spring was coming because the melting snow on our roof formed puddles on the plant floor below. Lights would short out.” A roofing contractor warned her not to walk on the roof.

The board wanted her to find a better building, but hadn’t set aside money nor bought land. She had to put a deal together herself. Naturally, she first approached the City of New Ulm for assistance, but initially received little more than a pat on the back and a vague promise that “something” might be done in five years. But with a dangerous roof, she didn’t have five years. So she scouted out potential buildings in Mankato and St. Peter, the latter practically “begging” her to relocate there. The City of New Ulm, seeing how serious she was about moving, finally began talks in earnest.

“It turned out to be a great deal for everyone,” she says. “Our old plant was near downtown and the City owned farmland out on North Broadway. So we swapped land with the City. We also received TIF, and a SBA loan. Our banker, State Bank & Trust of New Ulm, who recognized our potential, also loaned money. It was a patchwork quilt, but it did the job.”

The old facility had been 28,000 sq. ft. on three levels; the new would be 45,000 sq. ft. on one level, with six acres of land for expansion. The new office was large enough for all the supervisors to sit at a table without bumping elbows during weekly production meetings. And the roof didn’t leak. Company morale shot up.

But there were even more problems. Her predecessor, the former company president, had left a stinky public relations mess at his departure. “After he left, people were coming into the office and asking for the owner,” Fogelberg says. “But we didn’t have an owner. We have shareholders. In a way, we’re the Green Bay Packers of pre-cast.” (The Green Bay Packers are a public corporation, owned by thousands of shareholders.) She received mail for years addressed to “Owner” because the former president had touted himself as such. Apparently, he also put word out on the street that Artstone was for sale, which it wasn’t (and even if it were, it wouldn’t have been his responsibility to sell it) and Fogelberg had to handle all potential suitors. It was a public relations nightmare.

The company started in 1914 as Guggisberg & Saffert. Later, George Saffert bought out Guggisberg with the help of several prominent New Ulm townspeople. The company changed its name in 1932 to American Artstone, which perfectly described its principal product: artstone. (During World War II about 25 German POWs worked at American Artstone while on work release from the nearby prisoner camp in New Ulm.) Many of the current shareholders are members of the founding fathers’ families. Some children of former employees also own company stock — as do Fogelberg and current employees who opt to buy in after being employed three years.

The company can point to dozens of high-profile buildings in its main market of Minneapolis-St. Paul to prove its mettle. Its work at the Minnesota Science Center in St. Paul recently won a prestigious award. Other projects include the new convention center in St. Paul, Xcel Center, Ramsey County Government Center, Como Conservatory, and numerous projects on the campuses of St. Thomas, Macalester College and the University of Minnesota.

The high cost of shipping architectural pre-cast makes American Artstone noncompetitive outside the Upper Midwest. All orders are custom-made. Their main competitors are from Sioux Falls and Dubuque. It is common, Fogelberg says, for a business to want to chisel its name or logo onto a building — and it is this niche that American Artstone has chiseled out for itself.

Now that her Prodigal Son has finally returned home from losing its way, Fogelberg, 52, works hard to keep the company heading in the right direction. To accomplish that she lives in Jordan off Highway 169, far from New Ulm but closer to her No. 1 market, Minneapolis-St. Paul, and to four board members. She keeps her mind occupied on the hour-long drive down by thinking through the day’s challenges and listening to mystery books on audiocassette. “There are very few days I regret coming in to work,” she says. “There have been struggles in the eight years, but I like the job, the people, and I am certainly very proud of the product we put out.”

“It Wasn’t Me; It Was Jesse.”

In early 2000, a representative from the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) office in Mankato asked Nancy Fogelberg if they could nominate American Artstone for a statewide award. She said, “sure,” and didn’t think more of it until her banker, Mary Ellen Domeier, of State Bank and Trust of New Ulm, said, “Nancy, they don’t give this award to companies; they give it to people.” The award happened to be “Minnesota Small Business Person of the Year.”

She won, which meant a luncheon in Minneapolis and a photo op at the White House alongside the President of the United States. “I wasn’t looking at [the award] for myself,” Fogelberg says. “In fact, it made me very uncomfortable. I have always felt the success of this company was due to a team effort. To make the personal recognition more acceptable to me, I took the attitude that I was going as the poster child for Artstone.”

The SBA originally had scheduled her for a “Thursday” White House briefing, but a day before the trip was supposed to begin she received a correction notice. A revised itinerary had Thursday whited-out. “It seemed like a bait and switch,” she says a bit tongue in cheek, because she would have gone to Washington for the award ceremony anyway. Besides, by then she had secured hotel reservations, plane tickets and was ready to go the next morning. The President was knee-deep in trade negotiations with China, which forced the cancellations, she surmised.

On the way to breakfast her first day in Washington, somebody grabbed her arm. “Do you want to go to the White House?” an “official” looking woman asked. Nancy nodded. The woman said, “We can arrange it for tomorrow.”

There had been 53 recipients, but only 20 boarded the bus for the White House. Fogelberg was curious why others hadn’t been chosen. American Artstone was a relatively insignificant $4 million company out on the prairie hinterlands, while several dot.com millionaires running larger companies were kept off the bus. Another award recipient seated near Fogelberg, a black woman, had an answer to her question. “Look around,” she said, pointing to a busload of black Americans, Asians, and Native Americans. “All the minorities are on this bus.”

“But I’m not a minority,” Fogelberg shot back, and she was right. It bothered her for a few more minutes until she decided to shrug it away. “You know,” she whispered to herself, “I don’t care why they chose me. I’m going to see the President of the United States in the Oval Office.” She viewed it as a once-in-a-lifetime experience that would transcend politics — and any behaviors or misbehaviors of the current occupants.

Upon entering the White House, aides began by shooing her group into the Roosevelt Room, a West Wing waiting area dripping with tribute to Teddy, FDR, and Eleanor. She was quickly briefed there. Fogelberg was told to walk up next to the President in turn, wait for the pop! pop! of the White House cameras, and say her name and state before allowing the next award winner ten seconds of fame. Fogelberg was very nervous. Instead of freeze-framing a polite smile after saying “Nancy Fogelberg” and “Minnesota” — the way she had been briefed — in a fit of silliness she tagged on the word “Jesseland” in reference to being from Minnesota. (By the way: White House photographers caught the “se” in “Jesse” just right, and currently she has a nice picture with a toothy smile hanging in their New Ulm lobby.)

President Clinton picked up on “Jesseland” and launched into a protracted Jesse Ventura story. “Apparently he loves the man,” says Fogelberg. “Then a little light went on inside my head. Ah! I thought, now I know why I made the select group of 20. It seemed as if I had been chosen because of the President’s fondness for Jesse.”

While other recipients ate up their moments with President Clinton, pop! pop! Fogelberg just stood in awe trying to soak up all the history that had transpired in the Oval Office. She gifted White House aides with a sleeve of American Artstone golf balls, which were later acknowledged in a “thank you” letter signed by the President.

She attended a congressional luncheon afterwards, and shook hands with Minnesota Senator Rod Grams. A Grams aide, who was also a cousin of an American Artstone employee, gave her group a private tour of the U.S. Capitol. One highlight was standing in the Senate balcony. “We just sat there,” she said, “and watched all these Senators coming in for a vote: McCain, who had been campaigning; Feinstein, from California; and here comes lumbering Teddy Kennedy towards his seat. While the senators were piling in, our guide was giving a running commentary on each of the senators.”

And what did he say about Sen. Ted Kennedy? “See the desks they sit at?” he said, pointing at the floor below. “Kennedy’s desk has to be refinished every year because his spit takes the surface right off of it.”

© 2001 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

i have a company in iran producing pavement. we get so haapy if you send us your products information and show us the features of your products.

if we could work on them we can buy the knowlege of producing your products to produce the same products in iran.

thank you again

Sincerely yours

Ahmad Aghdaei