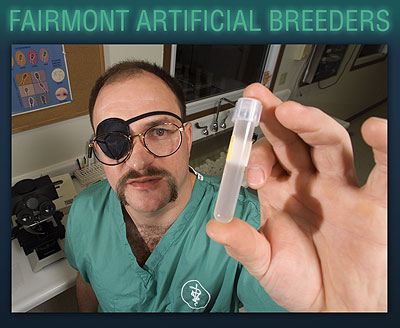

Fairmont Artificial Breeders

Photo by Jeff Silker

Haul a well-bred, 700-pound boar to a “genetic transfer station,” put him to work artificially inseminating hundreds of sows, and he’s worth $5,000.

Haul that same high-priced boar to market and he’ll bring $105 to $140 at the slaughterhouse, a humiliating 15 to 20 cents per pound.

The impressive spread between $105 and $5,000 is one reason farmers want to see value-added agricultural enterprises in rural areas. The price gap symbolizes why they’ve formed manufacturing cooperatives, converting beets into sugar and corn into ethanol, hoping to generate another source of farm income by adding value to products they already produce.

But profitability isn’t the only factor that motivates farmers to cooperate in joint ventures. Sometimes it’s a desire to drive up the quality of their products. For example, about 75 investors, all of them pork producers, launched Fairmont Artificial Breeders in 1995 as a way of improving the genetics of their herds. It’s organized as a partnership rather than as a cooperative, however.

The enterprise operates on 160 acres east of Fairmont, importing hundreds of genetically superior boars to sire thousands of high-quality pigs. Just off a gravel road running past this site, Fairmont Artificial Breeders built a genetic transfer station, commonly known in the industry as a “boar stud.” The station collects semen, processes it and distributes it in carefully measured doses to artificially inseminate sows. The 41- by 120-foot facility includes a laboratory and two isolation barns, all under one roof.

While many agricultural indexes declined steadily in the past six years, Fairmont Artificial Breeders grew 20 percent. “We now process about 360,000 doses (of semen) a year and we figure on another 20 percent increase by 2004,” said Doug Faber, who manages the facility. Most of the doses go to farms within 100 miles of Fairmont, although some are shipped as far as Nebraska and Montana.

The boars are brought to the facility when they’re six to seven months old, weighing 250-300 pounds. They reach their maximum semen output at 12-14 months of age.

The boars have a short career, however. By the time they’re 18 months old, weighing 700 pounds, they’re off to the slaughterhouse.

The genetically superior market hogs sired by these boars go to market when they’re six months old, weighing 220-270 pounds. They become flavorful roasts, lean bacon and thick pork chops. But boar meat isn’t that good, according to Faber. Packers use them for pizza toppings or spiced meat, an ignominious end for a $5,000 stud animal.

It’s not surprising that Fairmont Artificial Breeders emerged in Martin County. The county has some of the most fertile soil in the Upper Midwest and has always been one of Minnesota’s top pork-producing counties. The rich, black land has historically produced vast quantities of corn, which fattened small herds of hogs on many family farms.

In addition to capitalizing on their natural resources, Faber said Martin County farmers have been “aggressive in adopting new technology. They were quick to adopt the confinement system,” Faber said. Nowadays, small herds of barnyard hogs are as rare as horse-drawn plows. Most are raised in confinement buildings. The first such barns went up in the 1970s and by the early 1990s, their numbers “grew rapidly,” he added.

For at least a decade, Martin County has ranked No. 1 in pork production in Minnesota, according to Faber. He estimates the county’s hog population at 600,000, vastly outnumbering a human population of only 21,500. By comparison, nearby Blue Earth County ranks second with 400,000 hogs, according to Faber. The hog population “turns over,” however, as market hogs are sold to packers and replaced by new feeder pigs.

Rather than be subject to day-to-day market price variations, most producers have long-term contracts to supply processors such as Hormel in Austin, Swift in Worthington and John Morrell in Sioux Falls.

These market hogs are bred to produce the lean meat desired by consumers and most are sold to packers on a grade-and-yield basis. “They want the meat to be moist, juicy, and lean, with a good color,” Faber said. “Producers try to standardize their product, but they have to know what the consumer wants and what the packer will pay.”

As hog numbers proliferated, more farmers became interested in artificial insemination as a way of improving their herd quality. “Farmers wanted to maximize their genetics by getting good boars through the use of artificial insemination. They wanted to use artificial insemination to cut their genetic costs too,” Faber said. “It’s cheaper for them to buy semen than to raise boars and do the breeding.” It’s also more efficient than natural breeding, he said. “Using artificial insemination, one boar can service 200 sows. Otherwise, the ratio is one boar to 20 sows.”

Faber said Fairmont Veterinary Clinic, where he once worked as a veterinary technician, was “instrumental” in helping pork producers adopt this technology on their farms. “Farmers couldn’t do it on their own because of the technology of processing the sperm and the cost,” Faber said. The vet clinic began collecting and processing sperm from the best boars in the area in 1993, then helped train farmers to do the actual inseminating.

“We recognized the need for this fairly early in the vet clinic,” said Dr. Kent Kislingbury, who’s practiced in Fairmont since the late 1960s. “In talking to our good producers, they recognized the need for superior genetics because they were selling on a grade-and-yield basis to the packers.”

The clinic, which has eight veterinarians, mirrors Martin County agriculture. “One vet does beef and the other seven do swine,” Kislingbury said. “Our business now is 90 percent swine. When I started practicing, there were 18,000 dairy cows in Martin County. Now there are less than 1,500.”

Swine production has “breathed life” into the county’s agricultural economy, according to Kislingbury. “What changed Martin County was contract hog production, which gave young farmers a chance to raise hogs for other producers.”

The clinic served first as an incubator for the concept of an artificial insemination facility, then as a catalyst to shape that concept into a profitable reality. “The clinic set up the paperwork and the contracts, found the land, funded the start-up costs and formed a limited partnership to get it going,” Kislingbury said.

Six general partners launched Fairmont Artificial Breeders, then sold $3,000 shares to limited partners. Because shareholders are pork producers, the organization had a built-in base of semen customers. “The semen was gone (spoken for) when we started,” Kislingbury said.

Although farmers are sometimes characterized as independent, hard-to-convince individuals, Kislingbury said the new venture attracted them as shareholders because “they wanted to improve the quality of their product and make more money.”

Kislingbury, who also raises swine as a sideline to his veterinary practice, is one of the six general partners. The others are Lonnie Schwiger of Fairmont, Daryl Bartz and Jim Lewis, both of Welcome, Kevin Hugoeson of Grenada, and Larry Becker of Northrop. “These are all prominent hog producers in Martin County,” Kislingbury said. The six general partners comprise Fairmont Artificial Breeders’ Board of Directors, with Becker as chairman.

Producers began to see results fairly quickly, according to Kislingbury. “When the pigs sired by those boars started coming to market, they brought $1.80 to $2 more per hundredweight. That’s about $5 a pig.”

A premium of $5 per head means considerable extra cash since Martin County’s inventory of 600,000 hogs “turns over twice a year,” Kislingbury said. (Here’s the math: 600,000 x $5 = $3 million x 2 = $6 million.)

The boars that sired these higher-priced offspring come from Pig Improvement Co. (PIC), a highly specialized company well known among hog producers for superior swine genetics. Although PIC has several production facilities in the U.S. and Canada, Fairmont’s hogs come from a PIC unit in Aurora, Saskatchewan, Canada, north of Crosby, ND.

“Our first boars came from a PIC facility in Oklahoma, but these are much better,” said Faber, who’s managed the facility since it opened in August of 1995. He said PIC chose the remote Canadian location “for bio-security reasons. There are no other pigs within 20 miles. You can’t do that in Minnesota or Oklahoma or anywhere else.”

Because large numbers of pigs are confined in small buildings, they are susceptible to the rapid spread of contagious diseases, which could either destroy entire herds or limit productivity.

Producers learned long ago to keep casual visitors away from their herds and security procedures have gradually become more restrictive. “Most farmers won’t let you in their barns,” Faber said. Even when Fairmont Artificial Breeders trucks make deliveries, the semen doses “are put where we don’t come in contact with other pigs or pig traffic. We put it in a bio-secure place, but we don’t enter their barns,” he said.

This intense attention to security means “we don’t get to see our customers in person. We talk to them via fax, phone or computer,” Faber said. “The days of making house calls are done.”

It’s an aspect of doing business that Faber misses. When he worked as a veterinary technician for Fairmont Veterinary Clinic in 1989-95, he “liked dealing with livestock. I went out with the vets, did vaccinating, castrating, dehorning. We made house calls,” he smiled.

Faber grew up on a farm near Trimont, northwest of Fairmont, and finished a two-year livestock production program at Waseca Tech. College in 1989. Although he joined the vet clinic that year, he continued actively farming in partnership with his five brothers until the breeder group began in 1995. He remains a partner in the farming operating, but he is no longer active. The brothers farm 1,200 acres and milk a herd of 60 dairy cows. They’ve always been fairly diversified, raising beef cows, feeder cattle and swine in addition to row crops and the dairy herd. They built their first confinement barn in 1997 to house 1,000 head of feeder pigs.

Today he and his wife, Bethany, live in a comfortable new home at the entrance to the 160 acres owned by Fairmont Artificial Breeders. The house was built in 1998, more as a security measure than a fringe benefit, according to Faber. “The theory of having the manager’s house right on the property is to protect their investment. I’m right here in case the electricity goes off or if there’s a snowstorm or any kind of an emergency,” he said. The boar stud is heated with propane, but the cooling system is electrically operated. A standby generator kicks in if the power fails.

Security is just as tight at the facility as it is at hog barns around the county, perhaps even tighter. Anyone who wants to go beyond the tiny lobby, photographers and writers included, goes first to a shower room where they leave their street clothes behind. After showering, visitors are dressed in hospital-like smocks and rubber boots.

Faber and all employees go through the same regimen. “Everybody takes a shower here before they go to work,” he said. Their work clothing and shoes are kept at the facility, and anyone who leaves during the day must shower again when they return.

Besides Faber, the facility employs six full-time technicians who care for the boars and collect, analyze, process and package sperm. Each dose contains 2.5 billion sperm cells, but “we’re looking to see that number go down to maybe half that,” Faber said. That means the breeder group can produce more doses without adding more boars. “We think the technology will be there to let us use fewer doses and fewer sperm cells per dose,” Faber said.

The technology involves “deep uterine insemination,” using newly developed catheters to deposit the sperm in the uterus. Catheters commonly used now put the semen in the cervix, meaning the sperm cells must “swim” upstream to the uterus. “We’re helping with the research trials on that right now,” Faber said. Producers are experimenting to see which catheters and which methods work best, with Fairmont Artificial Breeders collecting the data.

Despite missing day-to-day contact with farmers, Faber said “I love what I’m doing now. We’ve got a great group of owners. It’s rewarding to work with that many individuals, all looking at the same common goal, which is the best quality product at the most efficient price.”

He’s particularly proud of a certification the facility received from the International Standards Organization, which offers a rating of quality usually sought by manufacturers, not agricultural enterprises. “We’re the first boar stud house in the U.S. to be ISO 9000-certified,” Faber said. Before granting this certification, ISO makes a detailed evaluation of an organization’s processes and procedures.

“When we say we’re putting that many billions of sperm cells in our doses, when we say we’re doing various tests, an ISO auditor comes in and verifies this by going through all our documentation,” Faber said. “There’s a lot of paperwork involved, but it’s important to prove to our customers that we’re doing what we say we’re doing.”

The ISO certification, received in November of 1999, may be a case of overkill, however. For pork producers, the $5 premium they’re getting from packers may be all the proof they need.

An International Flair

There’s an international accent to the hog business in parts of Southwest Minnesota.

Sasha Gibson of Fairmont, a reproductive physiologist, gives advice to pork producers in a distinctive British voice. Her husband, Kaj Jensen, lends a Danish dimension to the industry.

Sasha and Kaj live on acreage just north of Fairmont. Originally from Denmark, he manages Riverdale, Inc., a 3,000-sow unit near Lewisville in Watonwan County, which is owned by 15 area pork producers. He has bachelor’s and master’s degrees in animal production from the Royal Danish Veterinary and Agricultural University in Copenhagen.

Sasha has an undergraduate degree in animal science from Harper Adams Agricultural College in Shropshire, England, and a master’s degree in swine production from the Univ. of Aberdeen, in Scotland. Kaj attended the Univ. of Aberdeen for about a year and that’s where the two met.

She works for Preferred Capital Management of Fairmont, which provides management and marketing services to Fairmont Artificial Breeders, LLP. The breeder group is a partnership formed by pork producers to acquire genetically superior boars and use their semen for artificial insemination.

Preferred Capital Management is affiliated with the Fairmont Veterinary Clinic, which was instrumental in launching the breeder group in 1995.

Gibson said she and Barry Hilgendorf, Preferred Capital’s manager, have a mutual acquaintance, which explains how an Englishwoman came to work for a Fairmont enterprise. “One day Barry just called me,” she said.

Gibson worked in Fairmont during the summer of 1997, then went to Scotland to obtain her master’s degree. She returned to begin working for Preferred Capital in October of 1998.

Her primary responsibility is training pork producers in the techniques of artificial insemination. “But I also head up the community relations side of things,” she said. That involves preparing articles, arranging publicity and organizing trade show booths and exhibits. She helps represent Fairmont Artificial Breeders at pork industry trade shows in Minneapolis, Des Moines and Sioux Falls.

Gibson said she likes the “variation” of her job, as well as “the people, the freedom and the fast-paced aspects of being here in the States.” She describes the pork industry in general and producers in particular as “dynamic.”

“My hog producers are dynamic. They listen to an idea, then they go for it. They’re driven to be the best they can be,” Gibson said. Compared to their English counterparts, “they’re more futuristic, more optimistic.”

© 2002 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.