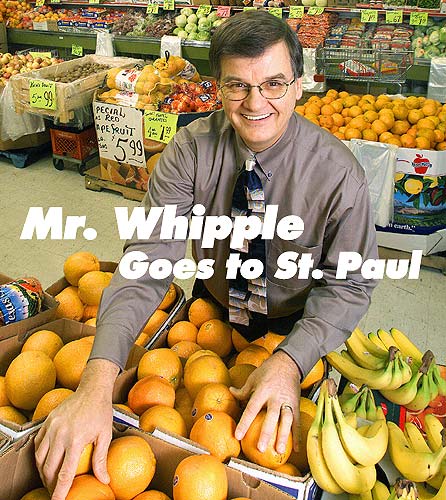

Rep. Bob Gunther

Photo by Jeff Silker

Rep. Bob Gunther, like Mr. Whipple, enjoys squeezing the Charmin — and periodically poking a finger into the Pillsbury doughboy’s tummy. In fact, his calloused hands and fingers are into squeezing and poking nearly everything.

Ask 100 people outside his hometown of Fairmont and they will describe Gunther’s poking and squeezing 100 different ways. The grocery industry leans heavily on his savvy: he co-owns Gunther’s Foods in Fairmont and Elmore, and understands grocery issues in minute detail. To corporate executives he’s the razor-sharp yet unassuming Republican point man on many job training and workforce development issues.

To fellow board members on the Chicano Latino Affairs Council he’s amigo. Seniors in rural Martin County know him as their taxi service. To parents of wayward youth he’s the advocate for the Minnesota Youth Intervention Program. Though many religious conservatives praise him for his rooted convictions, so does the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) for his stand on legalizing industrial hemp.

100 different ways — but mostly only one in Fairmont, where people knock on the office door to ask for “Bob.” He’s the friendly grocer with the sympathetic smile who will not only bag your oranges and bananas, but also load them into your trunk if that makes you happy.

CONNECT: I’ve heard your life was changed by a speed reading course.

GUNTHER: I was a very slow reader in high school, and didn’t enjoy school because of it. After leaving the Navy at 26, I took an Evelyn Woods speed reading course, and it opened up a whole new world. School from then on became easy, and I enjoyed reading where I hadn’t before. No one in high school knew I was a poor reader, and today I think about the school years I missed out on that I could have enjoyed.

CONNECT: What authors do you enjoy today?

GUNTHER: I love reading Louis L’Amour and Robert Ludlum. I also read a lot of technical material due to being a state legislator, and sometimes fall asleep reading government ledgers and accounting information. Thankfully, I have a staff to help with all the necessary reading. I read about 40 emails and 10 letters a day from constituents, but prefer responding on the telephone to get a better sense for what they’re feeling. I feel more comfortable talking on the telephone, and I think the person on the other end does too.

CONNECT: How many grocery stores do you and your brothers own?

GUNTHER: We sold two, and now have two. It’s not a great time for independent grocers. For years the Midwest was a bastion for the independent grocer because chains such as Kroger or A&P bypassed Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska, and the Dakotas. Now regional chains such as Hy-Vee, County Market, and the nation’s No. 1 grocer, Wal-Mart, are moving in. It’s difficult for an independent in a regional center such as Fairmont to compete with large chains.

CONNECT: You said you used to have four stores, but now two. When you sold two stores it must have hurt your negotiating power with suppliers, which made it more difficult to compete with the larger chains on price. What niches have you filled that the chains can’t or won’t?

GUNTHER: Our four locations were in Britt, Iowa; Fairmont; Elmore; and Wells. Selling two stores did hurt our bargaining power. But compared to the chains, our bargaining power with four stores wasn’t that much greater anyway. Hy-Vee as a company does more than $3.5 billion in annual gross sales, which certainly gets a supplier’s attention a lot faster than our sales figures. We compete through our rapport with customers, a quality my brothers and I inherited from our father. If there’s loyalty left anymore, we have it. In addition, the quality of our meat is known throughout the region. Our slogan is, “You can take the guesswork out of entertaining by buying your meats at Gunther’s!” We still bag groceries for customers, and place the groceries into cars. We try to do everything we can to make the shopping experience pleasant.

CONNECT: Do you get along with your brothers?

GUNTHER: I have four; three are business partners. I don’t always get along with them. I have a saying, said jokingly, that ‘I love my brothers 100 percent of the time, and like them very seldom.’ That saying isn’t completely true because I do like them a lot. However, it is tough to work all your life next to the same people. We don’t socialize.

CONNECT: Which brother has which function?

GUNTHER: Each has had his own interests. I was a buyer; one was a bookkeeper; another loved produce, etc. We have stayed intact, to a large extent, because of our father’s will. We were partners by birth. However, if one of the brothers needed help, all the others would line up behind him in support.

CONNECT: In the grocery industry the last 20 years, there’s been a shift in the way food manufacturers allocate marketing money. In the old days sales reps had “street money” to “grease the skids” at individual retail stores. Now the skids are greased at the wholesale level through “slotting fees.” The newer emphasis hurts smaller grocers such as yourself. Could you explain this shift?

GUNTHER: Twenty or 30 years ago salesmen representing every major manufacturer called on us, up to 40-50 sales representatives per week. Today we’re lucky to see three. As a rule, sales reps today don’t call on stores doing less than $120,000 a week in gross volume, and many companies have cut back in the number of salesmen. The “street money” isn’t there unless you’re a big player. It’s very evident to me that the “pop” companies, for instance, give Cub Foods and Wal-Mart better deals than they do the stores in Mapleton and Lake Crystal.

CONNECT: “Premiums” are incentives salespeople use to prod grocers into buying merchandise. What were some of the “premiums” salespeople gave you back in the ‘70s and ‘80s?

GUNTHER: We were given things like gas grills and VCRs. I heard that one grocery chain in Duluth received a $100,000 yacht on Lake Superior for buying merchandise. Those premiums, for the most part, have dried up. Now salespeople use price and terms as incentives to grocers — and the larger the chain, the more it can demand.

CONNECT: Aren’t there laws against that?

GUNTHER: There are, but the chains find gray areas.

CONNECT: The Robinson-Patman Act was enacted by Congress in 1936 to keep large retailers from dominating markets through predatory pricing, and from using their dominant influence to extract from manufacturers price concessions not available to small retailers. Are you saying Robinson-Patman doesn’t have any teeth?

GUNTHER: It offers far less protection to small retailers than the law originally intended. The courts over the years have watered it down. They originally said a wholesaler or manufacturer couldn’t favor one customer over another by selling product to one for less. It’s different today. Now the courts say you can’t sell product at a lower price to a particular customer, unless, of course, that customer buys more product; unless the wholesaler can cost-justify it; unless the customer is physically closer; unless the customer is in a different market from yours; unless television advertising, which is a very expensive media for a small retailer, is used by the grocer to qualify for extra money. These exceptions and others have watered the Act down. Wholesalers and manufacturers will give one price to a customer buying a straight railcar, and another to a customer buying a semitrailer, which holds less than a railcar. And then another price to us. I understand our vulnerability when I see chains receiving lower prices from suppliers. The chains would love to get rid of smaller independent grocers like us. I really believe, and I think I can document this, that their prices ultimately would be higher than ours are now if we were gone. The consumer would lose out in our absence. We’re the big chains’ conscience.

CONNECT: In 1997, you successfully introduced an amendment to an antismoking bill, HF117, which deleted language that would have prohibited tobacco manufacturers and distributors from paying “street money” to grocery stores to place tobacco products in eye-catching locations. Why was that so important to the grocery industry?

GUNTHER: Over the years, grocery industry studies have shown that product placed at eye level sells better than product on the bottom shelf, for instance. The industry axiom is, “Out of sight, out of mind.” It was very important to the tobacco industry for them to receive their share or more of those “good” shelves. So the tobacco companies and wholesalers determined certain requirements, and if the retailer fulfilled those requirements, the retailer received so much extra per carton. The practice was profitable to retailers selling large numbers of cigarettes. The racks were self-service and easier for the customer to make a purchase. Our Fairmont store sold a lot of cigarettes, and received substantial payments. However, the cigarettes were also easier to steal. The money I was receiving for shelf payments was watered down somewhat by theft. Keeping cigarettes less accessible to minors trying to steal them, and less accessible to adults wanting to purchase them — remember, “out of sight, out of mind” — had cost our store $20,000 in sales per year.

CONNECT: What are your margins on cigarettes?

GUNTHER: The law says retailers must make at least 8 percent. The minimum price is designed to stop larger retailers from putting smaller ones out of business.

CONNECT: But is it right to limit competition? This sounds like what happened last session when legislators established a floor price for gasoline retailers.

GUNTHER: It’s the same thing, and it applies to milk as well. I didn’t have anything to do with the tobacco 8-percent margin law, but I am guilty of the gas station law. These laws protect the “little guy” retailers from predatory pricing, and it protects the smaller tobacco wholesalers, such as A.H. Hermel in Kasota. Wholesalers such as A.H. Hermel wouldn’t exist without those laws.

CONNECT: Speaking of tobacco: do you in any way think it is wrong for the State of Minnesota to allocate 76 percent of its tobacco money to the general fund? What happened to compensating smoking victims? You yourself tried to set aside $10 million for juvenile diabetes.

GUNTHER: There is a difference between the tobacco endowment money, a onetime amount of $1.2 billion destined for medical research, and the ongoing tobacco settlement money based on the number of cigarettes sold in Minnesota. I proposed setting aside $10 million for juvenile diabetes research from the endowment money. As far as the ongoing tobacco money, the State of Minnesota has paid out billions for Medicaid and other health-related issues. Frankly, without the ongoing money there would be other people who would have to pay more taxes. That money is viewed by the State as a cash cow. The tobacco settlement money was supposed to be used for helping people stop smoking, but what disturbs me is that smoking cessation efforts have been ineffective. In fact, more young people seem to be taking up smoking, especially women, than before the settlement money. Smokers are paying nearly 50 cents a pack in taxes to Minnesota, and more to the federal government. The winners with the new money are state government, tobacco companies (because they increased the cost of their product more than it cost to settle), and the media, because smoking cessation ads are run through them. (To be fair, the media were big losers when tobacco TV ads were prohibited 30 years ago.) The tobacco industry is still healthy, and it was set back only temporarily.

CONNECT: Why your interest in juvenile diabetes research?

GUNTHER: I’m a diabetic. I know what 3-year-old children have to endure to manage their diabetes. We’re close to finding a cure, and very close to discovering ways to make children more comfortable with it.

CONNECT: Lobbyists out to kill the “Wine in Grocery” bill last session personally threatened you with ethics violations if you didn’t vote a certain way. Other legislators allegedly received death threats. What’s the story behind the story?

GUNTHER: The threats were overblown. The bill would have authorized the sale of wine in Minnesota grocery stores. Currently, wine is sold in grocery stores in 37 states, but not here. I don’t have a burning desire for Minnesota to have wine in its grocery stores. In fact, I think it would cost me more money than I could ever make because of having to purchase “dram shop” insurance. Right now our stores sell nonalcoholic and 3.2 percent beer, and don’t have to carry insurance. If we had wine, though, we would have to carry it. Dram shop insurance protects us from lawsuits resulting from people buying wine, driving intoxicated, and killing someone. It’s expensive insurance. Personally, I wasn’t that excited about the bill because most of my district is served by municipal liquor stores. Wine sales in our grocery stores would be taking money away from local governments. I really don’t like the idea of grocery stores selling wine. But the arguments the lobbyists were using against grocers were offensive to me. They were saying that grocery stores aren’t able to properly monitor what they sell, and consequently more kids would steal wine. To say that grocers aren’t responsible bothered me. As an industry we work very hard at being responsible with controlled substances. With tobacco, for instance, as a grocer I personally read the law to every one of my employees. I had employees read the law every month, and sign that they had read and understood it. Yet even with that, we were “stung” at our Fairmont store. A young cashier knew it the minute she sold a pack without checking I.D. We had to fire her. She personally had to pay a fine, and our store had to pay one, too. We were stung, and yet we had taken away from our customers any direct access to cigarettes, and done everything possible to stop youth from smoking or stealing them from our store. We live in an imperfect world. One employee forgot one time.

CONNECT: Given that, could grocers adequately safeguard against wine purchases and theft by youth?

GUNTHER: Fairmont police a while ago instigated a sting operation to stop the sale of alcohol to minors. Our store passed, but the city-owned liquor store failed. It was probably a momentary lapse on a municipal clerk’s part. If we won’t as a society make tobacco an illegal substance, such as in the days of prohibition with alcohol, then we will have to live with momentary lapses in memory or judgment by a clerk. One way to stop wine and tobacco sales to minors is for the federal government to say that everyone under 26 must show a picture I.D. That way all the pressure for compliance isn’t put on the clerk and store. The retailer would be sharing responsibility with the purchaser. I might draft a bill like that.

CONNECT: How were you allegedly violating ethics standards with “Wine in Grocery”?

GUNTHER: Some lobbyists were saying, “Gunther, you’re a grocer, and are just trying to find a way to make more money selling wine. It’s a conflict of interest and because of that you should excuse yourself from debate.” To use that logic, I guess Rep. John Dorn, because he’s a teacher, should excuse himself on bills involving education, and Sen. Hottinger, because he’s a lawyer, should do the same on bills involving judicial policy.

CONNECT: It’s rare that a new grocery built from the ground up goes belly-up its first two years. In fact, in my own 12 years in the grocery industry, I knew of it happening only once. What happened in North Mankato? Surely you heard industry rumors of what went on.

GUNTHER: A conventional “ma-and-pa” store was built on the North Mankato hilltop, with a new Cub Foods and a Hy-Vee right down the hill from it. On the Mankato hilltop was another Cub Foods and another Hy-Vee, and Rainbow, and Wal-Mart, and Sam’s Club. The competition was awesome. Apparently, the convenience of the hilltop North Mankato location couldn’t offset the competition. They didn’t have the marketing muscle of a large chain, either. Before a retail store opens in any town, its potential supplier(s) have to do their homework. They do telephone surveys in the town to determine need, research the competition, measure the physical distance to the competition, calculate traffic flow, and perform many other analyses. The City of North Mankato desperately wanted a store in that location to the extent it was willing to subsidize it. Consequently, a small grocer in lower North Mankato went out of business in part due to the city subsidizing that store. North Mankato wants to be separate from Mankato. I think they felt a grocery would enhance their image. It just didn’t work.

CONNECT: In your role as a legislator: What is CLAC? and your involvement?

GUNTHER: It’s the Chicano Latino Affairs Council. The Speaker of the House appointed me and another house member to it because I’m heavily involved in workforce development. Our dependency on new immigrants to fill job slots will increase. St. James and Madelia, which I represent, have a huge Hispanic population. In fact, last year in the public school in Madelia 51 percent of the kindergarten class had an Hispanic background. How we assimilate that population is important if we are to continue prosperity in Minnesota. We’ll need to educate them, and make Minnesotans out of them. The more I can help them become Minnesotans, the better off we’ll all be.

CONNECT: You’re the only man I know who’s had a report named after him: the Gunther Report. What purpose did that report serve?

GUNTHER: It blew my mind that no one in the legislature knew how many job training programs the State of Minnesota had. No one had a clue. So I decided to find out. I drafted a bill that required every state-funded job training program to report their mission and purpose, success, number of clients, and cost per client. We discovered that Minnesota had 83 different job training programs in 12 different departments of state government. It was a shock to learn that state government spends more than $200 million annually without anyone knowing the who, what, where, when, why and hows. I was embarrassed as a legislator to learn that no one knew the facts. After the first “Gunther Report” meeting I received 19 telephone calls from people who thought I was trying to put their training programs out of business. But that’s not true. I was only trying to put all the inefficient, duplicative, and unnecessary training programs out of business. If efficient and necessary, I wanted them to stay because we need good workforce development.

CONNECT: You want to legalize industrial hemp. Why does a legislator from perhaps the most conservative district in the state risk endorsing a weed that most voters think is marijuana?

GUNTHER: A certificate hangs on my St. Paul office wall that reads “Hemp for Freedom.” It was given by the federal government to a Sherburn farmer for raising industrial hemp during World War II. During both World Wars the federal government needed hemp for rope, and it was grown in Minnesota. The genus name for hemp and marijuana are the same, but they are two totally different plants. The weed growing wild in nearly every corner of Martin County, the industrial hemp, has almost no THC in it. THC is the drug in marijuana. I jokingly say that the “Entrepreneur of the Year” for my district was a young kid from St. James who picked wild, industrial hemp leaves near his farm, nuked them in his microwave, and sold them at the State Fair in envelopes marked, “Grass $25.” He sold $5,000 worth before being thrown in jail, but was released when tests showed the grass had no THC. The police gave him his $5,000 back and apologized. There are 921 known uses for industrial hemp. It returns $285 per acre, which is a better return than a good year for sugar beets. Blandin Paper Company has stated in committee at the Capitol that if hemp were legal they would contract for 100,000 acres of it initially and double the acreage every year for five years. That would be 1.6 million acres after five years, which would be one-seventh of Minnesota’s current corn crop. There’s a tremendous market for it. Farmers grow it in Canada, but not here because it’s on the federal government controlled substances list. In all honesty, if a farmer tried to grow “recreational” marijuana inside a field containing industrial hemp, the THC in recreational marijuana would be eliminated because of cross-pollination. It would be worthless as recreational marijuana. Industrial hemp takes the THC out of marijuana. A person might think the logging industry would lose out if industrial hemp were legalized, however, there is a projected shortage the next five years in the number of pulp trees. Industrial hemp could be grown on marginal land also.

CONNECT: Do you believe the “federalizing” of local public school education — transforming it from academic- to work-based learning through the use of the Profile of Learning and School-to-Work — will improve education?

GUNTHER: No. When you take the decision-making of our children’s education away from our local school boards, and our local school administration, and our parents, I think you are destroying the recipe for what made Minnesota schools the nation’s best. The idea of training someone to be more prepared for a job is an old one in schools. Because of a cutoff in funding we no longer have vocational wings in our high schools. Those programs prepared people for work. At one time we had six vocational programs at Fairmont High School. One function of our society is in not only providing a great academic education for our children, but also providing them with the tools to help them get a good job. I have a big problem with the federal government dictating the way this is to be done.

CONNECT: Fairmont is the largest city in outstate Minnesota without a college. In the early ‘70s, efforts failed to bring one to Fairmont. If the State won’t cooperate with funding, why can’t the City of Fairmont rent space from the high school, attract corporate sponsors, and begin its own technical college? Or begin an Internet-based college?

GUNTHER: If the push in the early ‘70s to bring a college here had been successful, today that college would be right down the road from where I live. Politics is the reason Fairmont doesn’t have a college. With the exception of one term, Fairmont has been represented by Republicans the last 40 years. Many people in Fairmont have said over the years that we don’t have a college because of the historic DFL control of the legislature. Whether that’s true or not, I don’t know. But I can believe it. My district has the least amount of state employees of any legislative district in the state. Out of 51,000 people in my district, which includes Martin, Watonwan and parts of Blue Earth County, we have maybe 40 state employees. My district goes from the Iowa line through Fairmont to St. James and Madelia, and includes Lake Crystal. The district has a Workforce Center in Fairmont, a license testing station, courts, two extension agents, five highway workers, and seven highway patrolmen. We could bypass the State to begin a college. With the Internet, you can site a college anywhere. Prairieland Extended Campus at Minnesota State University offers some classes through the Internet and interactive TV. However, there are 41 classes available through Winona State that we want in Fairmont and can’t get. MnSCU’s chancellor has told me we can’t have them, but won’t say why. Apparently there is a turf war going on between MSU and Winona State.

CONNECT: You seem to have a soft spot in your heart for the Minnesota Youth Intervention Program, and for talented youths interested in math.

GUNTHER: The youth intervention program is a good investment. It keeps wayward youth out of the courts and prisons, and more than pays for itself. The talented youth math program is now offered in Mankato through MSU. It’s amazing that a student can take a college-level, Calculus III course while in high school. I love math. Our gifted students are being shortchanged, and deserve everything we can give them.

CONNECT: You are an evangelical Christian. As a Christian, and not a legislator, what has been your biggest challenge at the Capitol?

GUNTHER: My most frequent prayer as a legislator is, “Dear Lord, let me be consistent.” I’m not asking Him to make me the wisest legislator; I just want to be consistent. I want to treat all people the same. I want to be true to my word, my principles, my ideals, and the people I represent. I have many Christian friends at the legislature, and we have a tremendous Bible study that includes legislators and staff from both sides of the aisle. I constantly remind myself that I work for the people of my district. I’m not their boss; rather, they are my bosses. As long as I keep this job as legislator in that context — that I’m there to serve them, not myself — I’m sure I’ll continue to enjoy it.

CONNECT: In December 2000 you won the bid again to run Martin County’s transit system. Fairlakes Transportation has more than 60,000 annual passengers. How did you become involved with that?

GUNTHER: In 1980, Fairmont’s city manager wanted a transit system, and advertised for bids. But no one responded. Older widows kept calling him, wanting to know how they were going to get groceries without a cab. He referred all the callers to me. Finally, after receiving all these phone calls, I walked into city hall one day waving a white flag. I told him I’d do it, but it would have to be run my way. The contract I signed said I wouldn’t lose any money, but it also said I wouldn’t make any money either. I was doing it as a service to the community. That agreement worked just fine until the State of Minnesota intervened in 1993 and said the contract wasn’t good enough. They forced the City to put it out for bid. Running the transit system is rewarding. We have expanded outside the city limits and into all the county. Martin County and Blue Earth County are similar: 50 percent of the population lives outside the main city. People in rural Martin County now have transportation. These are people that need help making medical appointments, and have had to rely on relatives or friends. Blue Earth County doesn’t have a transit system that reaches into the rural areas like ours. This issue was one of several that inspired my run for office. (After being elected, my wife took over the transit system.) One other reason I ran was when I realized that Greater Minnesota wasn’t experiencing the same prosperity and growth as the Metro area. I want to eliminate some of those barriers for growth. Our challenge is going to be even greater after redistricting.

CONNECT: How have you balanced business and the state legislature?

GUNTHER: It hasn’t been easy. When I first became a legislator, after working 60-70 hours during the week in St. Paul, I returned to Gunther’s to work on the weekends. I expected to have more time to work when we were not in session, but with meetings, fairs, parades, and constituent service it has become a full-time job. I found I had to make a choice. Even though I loved being a grocer, and worked at Gunther’s many years, I have now finally found a job that I not only enjoy, but one that gives me the opportunity to make a profound difference in the lives of others.

Rep. Bob Gunther Biography

Born: 7/12/43.

Family: Married, 1 child.

Education: Fairmont High School, ‘62; St. Cloud State University, B.S., Marketing

First Elected: 1995.

Legislative Committees: Commerce, Jobs, and Economic Development; Crime Prevention; Jobs and Economic Development Finance (Vice Chair); Regulated Industries.

Memberships: Bethel Evangelical Free Church; Fairmont Chamber of Commerce.

© 2002 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Pingback: Connect Business Magazine » Off-The-Cuff » Spring

That was so interesting. Go Bob gunther. F