Meter-Man

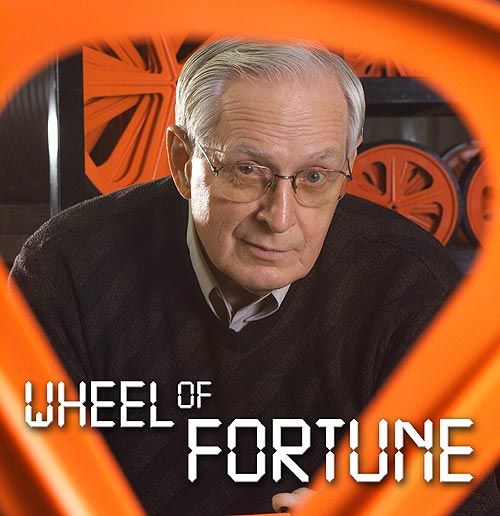

Photo by Jeff Silker

Listening to 70-year-old Lyle Stevermer talk about his company is like watching an inquisitive man trying to pencil in a Sunday New York Times crossword puzzle for the first time. He has lots of ideas, but doesn’t know where he will put them all.

He has owned Meter-Man of Winnebago, Minn., since 1963 — having begun it after winning “Grand Champion” honors at the Minnesota Inventor’s Congress — and the last ten years his business has been bursting its seams. As it is, he owns seven buildings in downtown Winnebago, having methodically sewn them together into a Joseph’s coat of many colors, a hodgepodge complex of aging buildings specifically refashioned to help Meter-Man better compete in a global economy.

In fact, this mild-mannered, affable, former Easton hog farmer, has had a decades-long litany of growing need for space. Listen in: “We started in 1963 in a small building on the south end of Winnebago, and in 1965 moved uptown where we bought a former department store. Then we took in the Gamble’s store, and the jewelry store, and the dentist’s office, which is where my office is today. The building to our south was a restaurant, and we tore it down to add on. In 1972 we bought the former Roxy Theater. A number of years ago we purchased and renovated what used to be City Hall. We also have a 60×120 metal building on the south end of town that we bought from Cargill years ago.”

And Stevermer didn’t even mention Meter-Man’s jam-packed warehouses in The Netherlands and Paraguay that move 17 basic products out to 38 countries. Further proof of the company’s growth and global reach is in its waiting room guestbook, which has names scribbled in from Hungary, France, England, The Netherlands, Canada, and Germany.

Who would have thought Winnebago would become Faribault County’s gateway to the world?

While there isn’t an accurate way to measure global market share in the industries of “distance measuring wheels” and “agriculture-related products,” Meter-Man could still safely lay claim to being “The World’s Largest Manufacturer of Distance Measuring Wheels” — if it were so inclined. Most companies hungry for a selling point would make use of a slogan like that; however, to a former Easton hog farmer raised on Midwest modesty, such a claim is simply too much brag.

After prodding from this curious writer, though, he did let slip that Meter-Man “has more than a 50 percent share in distance measuring devices in the U.S. and Europe — and we are strong in Australia, New Zealand, and have growth opportunities in Canada and Mexico. Our main overseas competitors are in England, China, South Africa, and India; and we have several domestic competitors. In essence, we have the leadership position in the world, mainly because we also manufacture private label product. We ship to some countries that I hadn’t even heard of before the order came in. And I wonder, What in the world could they possibly be using it for?”

Though Stevermer has 100 percent ownership and controls most aspects of product design, day-to-day operations are managed by the ownership team of the future: Lyle’s daughter Sharon, 40, (purchasing, regulations and export documentation), his son David, 45 (facilities, equipment and production) and son-in-law Jim Ness (marketing and sales). It has been a family affair for about 20 years. At 70, Lyle now spends months at a time in Mesa, Arizona, enjoying his hobby of gliding along at 5,000 feet aloft in the western sky — and when he has, these three family members along with a loyal cadre employed more than 20 years have been keeping the business humming.

“They have all worked together long enough now that I don’t have any apprehensions about the business continuing on after me,” he says. “In fact, the business probably carries on a little better when I’m not here. Though I do only product design now, they are heavily involved in that function as well.”

Business for the 30-employee company breaks down nicely: fifty percent in distance measuring wheels and fifty percent in agriculture-related products. About 70 percent of the distance measuring wheels are sold overseas, which translates to 35 percent of Meter-Man’s overall business. Garnering overseas market share has been a top priority, and its success in doing that led to the company being named Minnesota “1997 Exporter of the Year” by the U.S. Small Business Administration.

A Meter-Man “Distance Measuring Wheel” measures distances for dozens of real-world applications, from real estate appraising and surveying to law enforcement and athletic competition, while its user walks alongside. The brains of the “wheel” is a mechanical counter — and in the newer models, a digital counter — that resembles a car odometer, except it measures feet or meters. The wheels range in size from 4” for indoor use to 25” for most forestry and agricultural applications over rough terrain. The company website, www.meter-man.com, makes a strong sales pitch: “You’ve just discovered the easiest way to perform a large amount of measuring in a short period of time — just put down the wheel and go!”

The agriculture-related products are mechanical and electronic acre counters, electric fences, a power mister that inhibits bacteria and mold growth in livestock confinement facilities, and a livestock cooling system with programmable “On” and “Off” times, which was first tested thirty years ago by Lyle’s cousin Emmett, a Ph.D., then an agriculture professor at Iowa State Univ.

Meter-Man’s space problems became more pronounced in the early ‘80s after son-in-law Jim Ness, a former dean of students at private schools in Minneapolis and New Ulm, came on board to “really go after the world market,” says Stevermer. To attract a global customer base Ness began doing all the right things: advertising globally, attending international trade shows, and working with the Minnesota Trade Office. He began a steady diet of world travel, and sales grew, thus leading to the present space dilemma.

“We now have seven buildings in four main locations,” Stevermer says, referring to the hodgepodge of downtown Winnebago real estate. (Four buildings are adjacent along U.S. 169 and are connected by a labyrinth of passageways.) “Due to today’s competitive climate, we need to be more efficient, and the present complex of buildings doesn’t allow us to do that. We’re on two floors in one building, which isn’t convenient for running fork lifts and pallets jacks, and we have a number of wood floors not suited for production. And we’re constantly running a forklift across Highway 169 traffic over to the former Roxy building.”

The management team this year scoped out two potential buildings, including one in nearby Blue Earth; but Stevermer really doesn’t want to leave Winnebago, where many of his loyal employees call home. If the company did relocate it would have the added challenge of having to sell seven buildings in downtown Winnebago that were remodeled to accommodate Meter-Man’s specific needs.

Meter-Man does have needs besides space. Being competitive on price in a global economy also grabs its attention and focus, and affects every single person every day at the business, including purchasing, marketing, production — and even travel costs: salesman Ness flies coach on trips to Europe. Stevermer tries to design product that can be produced efficiently and inexpensively. “We don’t need a lot of bells and whistles because they cost money,” he says.

One competitive threat comes from the Land of the Rising Sun, China, where a manufacturer named Cen-Tech four years ago began “knocking off” Meter-Man’s distance measuring wheel — even down to copying old Meter-Man tooling and design flaws. Initially, Cen-Tech gained entree into the U.S. by offering ridiculously low prices to wholesalers. “Essentially, it’s a U.S. import house that uses cheap Chinese labor,” says Stevermer.

“Their presence was certainly a wake-up call for us,” he warns, “and it should also be a wake-up call for America. What China is doing today is what Japan did years ago by importing our technology and machinery to copy our products. Japan became a threat to us 25 years ago, but has gone by the wayside. Now the Chinese are cleaning Japan’s clock, and before them it was South Korea’s.”

Its competitors’ advantage in having lower labor costs (mainly in China, Mexico and South Africa) have been muted so far by Meter-Man’s better tooling, design and purchasing functions, he claims. “We have to be better, but that doesn’t mean we’ll always be. We have to keep improving.”

The company also stays competitive by adjusting to changing markets. In the “old days,” Meter-Man sold most of its agriculture-related products through farm implement dealers, such as John Deere, Case, and International. But as the farm economy consolidated, so did the number of dealers. Currently, the company focuses on selling to larger hardware distributors and “big box” companies like Menard’s and Home Depot. “We might like to think the ‘big box’ stores dictate prices, but in the bottom line, the world manufacturers establish the prices,” he says.

Freight costs are another variable — and establishing a warehouse in The Netherlands has helped lower costs to a key market, Europe. “Our tariff in The Netherlands is based on our cost of producing the product, and then it is shipped duty-free to all Europe. If we shipped direct from the U.S. to the end user in Europe, the tariff would be paid on the end users’ cost, which would be much higher. Our warehouse in The Netherlands keeps our prices lower, it’s centrally located, and it has good connection points.”

Given the competitive climate, many American manufacturers in Stevermer’s shoes would in the least entertain thoughts of farming out most or all of their production functions to lower-cost countries. It’s a logical thought, but not one that will ever cross Stevermer’s mind — for two reasons. “First, in particular, I have personal problems sending business to China,” he says. “ I spent time on the front lines in Korea fighting the Chinese. I do not have a strong love for them as a nation. The second reason we would never send business overseas is almost as important. Let’s say we had all our tooling in China and the U.S. had a major political disagreement with them. It’s easy for me to imagine that we could go without supply for months at a time. For example, a competitor of ours had a container-load of product shipping in from offshore, and it was locked up temporarily after September 11. They couldn’t get to it.”

THE FAMILY LINE

David Stevermer, Lyle Stevermer, Sharon Vriesen, Jim Ness and the line of Meter-Man measuring wheels.

AND THEIR BIGGEST CLUNKERS?

Not all of Stevermer’s inventions have tasted success. Some were clunkers that died a slow death for lack of customers and others failed because they were an unworkable solution to a real-world need. One such invention was Meter-Man’s “Universal Measuring Wheel,” which Stevermer designed to work alongside combine headers to tick off acreage. A heavy metal was used in the design to help the product navigate rough terrain, rocks and mud, which in turn drove the market price too high.

Another product was produced to meet a distributor’s perceived need: a distance measuring wheel adapted to hold spray cans upside-down. With it, a user could measure distance, pull a trigger and spray, for example, threads of lines for parking lot marking. The distributor bought a few hundred. “I knew at the time it wouldn’t fly,” Stevermer says, “and why I didn’t stick with my own personal convictions I don’t know.”

Nearly all his inventions and improved designs originate from his talking with a good number of people first to determine market need and demand. And then he, along with his upper management team, attempt to fill the need and demand efficiently and cost-effectively. Many products die in the idea stage. “There is no standard formula in inventing a product,” he says. “My mind is always thinking day and night, which is not always a good thing.”

A potential new product begins as a crude prototype. A market analysis is done, and distributors offer their two cents worth. “Then you start thinking about how it can be mass produced, which usually involves tooling because a majority of our products are injection-molded. We own about 200 very expensive molds. So we have to determine whether we can justify spending $20,000 for a mold to make a part. After that, we determine piece price. An average product has 40 parts. The final piece of the puzzle is to determine sales price. Not every one of our products is a winner.”

SCOOPING UP A GRAND AWARD

Lyle’s initial invention, a “metered” grain weigher from which the company took the name Meter-Man, is no longer manufactured. As a 30-year-old Easton hog farmer in 1962 he had sought a more precise grain measuring system, and his father’s machine shop near Easton provided the tools and heavy-gauge metal. “In that day the common ‘measurement system’ on a farm was to count the number of shovels of corn tossed into the grinder/mixer,” he says. “There were about 20 pounds to a scoop, but it wasn’t exactly 20 pounds. Grain flowed through my invention, weighed it, and tallied the amount. My parents encouraged me to take it to the Minnesota Inventor’s Congress, where it won ‘Grand Champion.’”

He quickly pursued a patent, but hasn’t on any invention since, mainly because he believes the process isn’t worth his time or money. It’s much better, he feels, to expend his energy producing efficiently and to move a product to market fast. “Being first on the market with a competitive price discourages a lot of people from copying you,” he explains. “Even with a patent, if someone infringes on it, it’s still up to you to spend the money to settle the matter.”

© 2002 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Nice article. I carefully read labels and do not buy products from China. That would be as smart as buying shoes that hurt my feet and cause permanent damage. Be careful what you import you may get it.