Timeless Images in Metal

Photo by Kris Kathmann

HELP WANTED: Immediate opening for marketing professional to spread word about neat stuff made by inventor/artisan/craftsman. Must make up for 30 years of lost sales. Call 507-278-4302.

Arnie Lillo never placed that ad. He’s more interested in conceptualizing and creating than in selling his creations. He holds three patents and passed up several others. But not one of his ideas put him on a road to fame and fortune, for a variety of reasons.

This, however, is not a story of failure. It is a chronicle of Lillo’s success at skipping the 9 to 5 world so he can let his creativity run rampant and make magic with metal. He has a surplus of talent, so that’s not holding him back. The problem, it seems, is marketing. To be more exact, it’s Lillo’s distaste for marketing.

“I’m not a salesman. I don’t like marketing. I really live to build this stuff, not sell it. I like to do stuff that other people think is impossible or really hard to do. That’s what really motivates me, doing the impossible or the next-to-impossible.”

Lillo enjoys it so much that in 1998 he shucked all the security, seniority and benefits of his job as a refrigeration mechanic at Minnesota State University, where he’d worked since 1984. Now he hangs out in the metal shop on his acreage between Mankato and Good Thunder. “I came home one day and told my wife I’d decided I really wanted to work in my own shop and do metal work,” he said. MSU was a “nice place to work, but there’s more to life. I didn’t have enough time to do what I really love to do, which is to invent stuff, design stuff, build stuff.”

His shop is home to “Timeless Images in Metal,” a company he formed two years before leaving MSU. Milt Toratti of the Riverbend Center for Enterprise Facilitation suggested that name. Riverbend offers counseling to entrepreneurs who want to start a business.

Lillo is a practical inventor with an artistic twist. His creativity earned him an invitation to the White House, where a commemorative plaque he designed and crafted was part of a 1999 exhibit focusing on national monuments. He then designed a limited edition plaque as a fund-raiser for New Ulm’s effort to restore the copper-covered statue of “Hermann,” a legendary German hero credited with liberating the Germanic tribes from Roman rule. (People who contribute $1,000 to the statue restoration effort get a signed and numbered copy of Lillo’s Hermann plaque.)

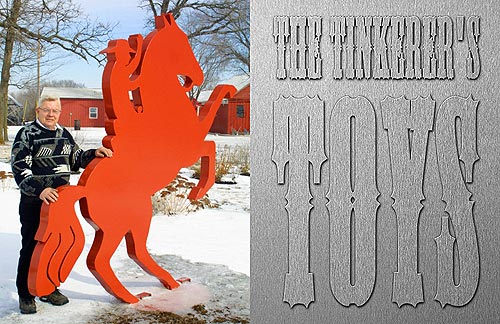

Lillo delights in cutting and welding “yard art” like five-foot weathervanes and life-size steel sculptures of horses. He’s developing a reputation for bringing back the past as a restoration expert. When a 1998 tornado ripped the 29-foot weathervane off the Nicollet County Courthouse roof in St. Peter, Lillo replicated it. He didn’t have much to go on, just a piece of the shaft, half the letter “N,” which stood for “North,” and three small photos.

Word of Lillo’s St. Peter accomplishment trickled south to Fairmont, where Martin County officials wanted to restore a pair of copper-covered eagles. Four such eagles once perched on the courthouse roof. Two disappeared many years ago. High winds ripped a third from its perch 35 to 50 years ago, so it was stored in the courthouse basement. The fourth eagle still stood atop the courthouse, but Lillo exchanged its rusting support pole for a stainless steel rod.

Lillo restored the two eagles, which are about four feet tall with seven-foot wingspans. They are fashioned from sheets of copper. Lillo took the eagle from the basement, pounded out the dents, fashioned new copper sheeting, and replaced a section between the wing and body. He also repaired several bullet holes. “Anything up that high, for that many years, is apt to have bullet holes in it,” Lillo said. The eagle’s wounds came from a large-caliber weapon, “definitely bigger than a .22,” he said. From the angle of the holes, it appeared someone standing near the courthouse fired the shots, Lillo said.

Collectors who want to make their vintage farm tractors look like new also turn to Lillo because of his metalworking skills. He’s producing replicas of the original steel side panels that covered the engines. That’s a relatively new venture, a niche market he discovered when a collector approached him about making a pair of side panels for an old Massey Harris tractor. “He told me there’s a demand out there for sheet metal parts for old tractors,” Lillo said. “The more we talked, the more interested I got.” Making parts for vintage tractors may lack the thrill of invention, but it promises a steady stream of revenue, something his yard art and his three patents failed to produce. When Lillo received his first patent in 1972, he was ecstatic. “I thought I’d be living high on the hog, but that wasn’t the case.”

What he patented was a cook-and-ride oven that strapped to a snowmobile’s muffler. It used the muffler’s heat to cook a hamburger in 10 minutes while the snowmobiler raced along the trail.

Timing, not lack of marketing, killed the idea. “That’s when the bottom fell out of the snowmobile business. Companies were going broke. They thought it was a good idea, but nothing ever happened. The timing was bad.” The idea isn’t likely to be resurrected. On today’s sleek snowmobiles, there isn’t room for a muffler-mounted oven. Lillo’s U.S. and Canadian patents expired more than 10 years ago.

Lillo also thought he had a winner in 1976 when he patented a wood-burning furnace for mobile homes, complete with a gravity-feed chute that supplied the furnace with wood. The furnace was installed outside the mobile home, to minimize fire hazards, and the gravity-fed supply of wood meant the homeowner “only had to go outside a couple of times a day to put wood in.” As the furnace consumed a log, the next log’s weight forced it down the chute and into the firebox. Lack of oxygen blocked the flames from creeping into the tightly covered chute. A blower circulated hot air into the mobile home’s duct work.

“I thought that idea would go,” Lillo said. But he made and sold only about a dozen of the units. Marketing seems to be the culprit. “I didn’t have the money to do a lot of advertising or get a factory going. I never tried to sell (the idea) to a company because I was going to make them myself.” Today you can buy a furnace just like Lillo’s from at least one Minnesota company. “I don’t know where they got the idea, whether they came up with it on their own or they saw mine,” he said.

That’s not the biggest boat Lillo missed as an inventor, however. “The one I really screwed up on big time is called a lock-out/tag-out device,” he said. “It goes on a steam valve or anything with a handle that has to open and close. You padlock it so no one can use the valve.” OSHA now requires such devices. They accommodate several padlocks, preventing equipment from operating accidentally or during a repair process. “If you’re a steamfitter, an air-conditioning serviceman or an electrician, you can padlock the line. It won’t work again until everybody has cleared their locks from it,” Lillo said.

Lillo designed his during the late 1970s, when gasoline prices skyrocketed and theft from rural storage barrels became common. The 300-gallon gas barrel on Lillo’s acreage was a tempting target for thieves. “I could put a lock on the hose, but they could still open the filler cap on top and steal gas,” he said. “I invented a device that would go around that cap. It’s still there today.”

Unfortunately, Lillo didn’t apply for a patent. “I thought of the idea, drew it out on paper, but my other ideas hadn’t gone anywhere, so I filed it away. Two years later, I ran across my notes. I still thought it was a good idea so I contacted my patent attorney.”

The attorney, however, found such a device already had been patented. Ironically, the other inventor and Lillo seemed to have been hit simultaneously by the same brainstorm. “The two of us had the same idea at the same time. The ‘date of invention’ on his patent was the same as mine. I could take a copy of my drawing and lay it down on his and it was like a carbon copy,” Lillo said. “Unfortunately, he patented it and I didn’t. It wasn’t until I saw that guy’s patent that I realized how big it could go. But by that time, it was too late.”

When he says “too late,” there’s no bitterness, no regret in his voice. He seems blessed with a basic good nature, too fascinated by today’s challenges and opportunities to look anywhere but ahead. He happily surfs the Internet, prowling for illustrations he might mimic in his yard art. When he wanted a rider astride a horse rearing on its hind legs, he found it on a Lone Ranger web site.

At 63, Lillo is old enough to have been a fan of the Lone Ranger, star of a long-running radio series and many Saturday matinee movies. He grew up with seven brothers on a 280-acre grain farm near Oklee, a town of about 500 on the east side of the Red River Valley. “I didn’t finish high school because I started cutting and hauling pulpwood to help the family through some tough times,” Lillo said. (He earned a General Equivalency Diploma from Mankato High School in 1964.) 1958, he married his wife, Janice, who was from nearby Brook, an even smaller town than Oklee.

Eventually, Lillo’s father sold the farm. “If I’d had the chance, I would have bought it. As it turned out, the way the economy and the weather has been up there, it would have been a bad investment,” Lillo said. Still, farming never lost its appeal. “I guess it’s in my blood,” he said. So, apparently, is his creative streak. His father and grandfather were no slouches when it came to inventiveness.

“When I was just a little kid, I heard my grandfather was the one who invented the tracks for the tank. That’s always stuck in my mind,” Lillo said. “I never asked him about the tank tracks. There are a lot of things I wish I’d asked, or taken notes, or got in writing.”

Although the tank tracks remain a mystery, Lillo saw many examples of his grandfather’s creativity. “One thing that comes to mind is a saw for cutting down trees, then cutting them up. He took a circular saw blade, about 24 inches in diameter, mounted it on two wheels with a motor, so the blade was out front,” Lillo recalled. “It had two handles so you could wheel it around in the woods. The blade turned so you could shove it into a tree and cut it down. Then you could tip the blade to vertical and cut the wood into lengths. I was only 10 or 11 years old, but I was really impressed. He was a great mechanic.”

Lillo remembered that his grandfather “didn’t have a dime to his name.” That same condition existed in his family. “Things were tough on the farm. No money, no luxuries of any kind.” To raise a little cash, his father built a tractor-mounted contraption to harvest the fluffy down from cattails. “Some outfit in Thief River Falls was buying it for insulation in Army clothing, sleeping bags or something like that. It was a chance to make some extra money,” Lillo said.

“My dad had a good mind. He built a deal that went on the front of the tractor, 10 feet wide, with fingers made of wood lath, spaced half to three-fourths of an inch apart. We’d drive through a swamp and the cattail stems would go between the fingers and the fuzz would be stripped off.” He and his brothers would scoop the cascading brown and white fuzz into burlap bags.

Lillo encountered tough times of his own in his first years off the farm. He moved to Milwaukee to work in a foundry, but was laid off twice. He and his wife returned to Oklee, living in a trailer house on the farm while he drove a gravel truck at Hawley. In 1959, his parents quit farming, rented their land and moved to jobs at Bethany College in Mankato. His father became a boiler operator and his mother became a college cook.

Lillo and his wife also decided to look for jobs in the Mankato area. He worked briefly in a stone quarry before Bethany College hired him as a janitor and his wife as a cook. In 1963, he began to get in touch with his talents, taking a job with a heating and air-conditioning firm and beginning an apprenticeship to become a journeyman sheet metal worker. After finishing the four-year sheet metal apprenticeship, he also took the two-year refrigeration course at South Central Technical College in North Mankato. He spent two decades working for various Mankato contractors and even became certified to teach environmental systems at South Central. After working all day, he taught evening classes for three years, which didn’t leave much time for tinkering or inventing.

In 1984, he became MSU’s only air-conditioning and refrigeration repairman, servicing everything from drinking fountains to 600-ton steam absorbers. “I enjoyed the work,” Lillo said, but as the years passed he longed for the freedom of his own metal shop on the 13-acre hobby farm he and Janice bought in 1969. It’s a place that satisfies his dual loves, tilling the soil and shaping metal.

“I don’t like living in town. I just love farming. It’s in my blood, I guess. I like to work with the soil,” he said. “Some people like to sit around and watch TV and do nothing. I can’t do that. I like to be out doing something.”

Lillo keeps busy producing antique tractor panels, servicing air conditioning systems on modern tractors and combines, cutting 10-gauge steel into bumpers for semi-trucks and tinkering with ideas.

His farming equipment wasn’t fancy, a 35-horsepower tractor dating back to the 1950s and two combines of nearly the same age. The last time he used it, he harvested about 100 bushels of soybeans. “It’s wasn’t a money-making proposition, but I got enough yield to pay expenses.”

There was a time when Lillo did make money farming, but it wasn’t soybeans. He grew ginseng, an oriental herb, for about 15 years. “The best I ever got was close to $60,000 off an acre and a half,” he said. That’s when the ginseng roots sold for $58 per pound. He quit raising it four years ago when prices plummeted to $12. Besides, it’s a labor-intensive, expensive pursuit and he wanted to spend more time in his shop.

Lillo’s acreage is in the hill country between Good Thunder and Mankato, an area carved into ravines, timbered hillsides and valleys by three rivers, the Maple, Cobb and LeSueur. It’s an out-of-the-way farmstead distinguished by a sprawling collection of yard art. “It’s probably the only yard around that’s got this much iron in it.” Lillo agrees that if the display fronted on busy Hwy. 169 or 14, it might attract more buyers. “I’ve taken pieces to Pioneer Power (an annual antique farm machinery show at LeSueur) and it sells good, but I don’t like to do it,” he said. (The art may get more exposure soon because a retail chain has expressed interest in selling it at their new outlet in New Ulm.)

Still, Lillo’s yard does attract some attention, despite its isolated location. “You’d be surprised at the number of people who drive by, stop and take pictures,” Lillo said. He recently found a woman and her two-year-old grandson, sitting in a pickup parked in his driveway. “The excited look on the little boy’s face made my day.”

Ideas, Ideas, Ideas

Observation, idle conversation and middle-of-the night inspiration generate ideas for inventions, according to Arnie Lillo.

The idea for a snowmobile oven he invented came from a co-worker who often placed a can of soup on a hot steam pipe an hour before lunch. “Then he had a hot meal while I sat eating a cold sandwich,” Lillo said. That led to his first patent in 1972, a muffler-mounted oven that would cook a hamburger using the muffler’s heat.

More than 20 years later, Lillo came up with a patentable design for an ice saw because of an idle conversation. “I was having a cold beer on a hot day, talking to a guy from up north about ice fishing. He wondered if I could build an ice saw because he couldn’t find one.”

Lillo designed a saw that “looked like a big pocket knife, with a steel blade that folded into a solid oak handle.” The sharp steel could cut any size hole, square or round, through ice two or three feet thick.

But to build it, Lillo had to buy a $15,000 plasma cutter with an electronic eye. A plasma cutter uses electricity as a flame. “It’s cheaper, easier, faster and more convenient” than an acetylene torch, according to Lillo. The electronic eye guides the torch to follow patterns, making it possible to build exact replicas.

He built 50 of the saws in two sizes, with blades three or four feet long. “I went to some big companies to try to get them to handle the saw, but they asked for my product liability insurance number,” Lillo said. “They said they couldn’t talk to me unless I had product liability insurance. The premium for that insurance was $9,000 a year and that was out of the question. I wasn’t going to sell that many saws at $120 each.”

Lillo never pursued a patent, but sold 25 of the saws himself. The other 25 are stored in his shop.

Sometimes ideas really do come out of the blue, according to Lillo. “I woke up at 2:02 a.m. one morning with an invention in my head, fully detailed, wiring and everything. I got a pad of paper, started writing and sketched it out,” he said. It was a portable security device, a length of pole ending in a heart shape containing a smoke detector. It could be leaned against a door with the heart fitting under the door handle. “It was dual purpose. If somebody pushed against the door, it activated the smoke alarm. I ran a patent search and it was patentable, but I didn’t do anything with it. I didn’t have the money.”

Inheriting a tendency for inventiveness also helps foster ideas, of course. Lillo seems to have inherited that trait from his grandfather and father. In turn, he’s obviously passed his metalworking abilities down to his two sons, Greg and Mark. Both work at Jones Metal Products in Mankato. Greg also helps his father in the Timeless Images shop, turning out products like tractor panels.

© 2002 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.