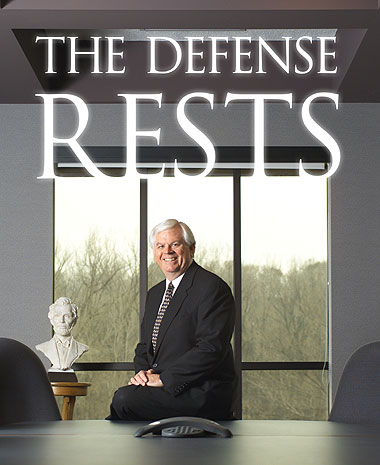

Dan Gislason

Photo By Jeff Silker

Dan Gislason digs the Icelandic countryside.

It’s a winter wonderland of crystal-clean waterfalls and gargantuan glaciers, an arctic canvas of white and lipstick red homes nestled against pastel-green Ansel Adams ridges. Iceland is a cornucopia of mentally stimulating sights and refreshing sounds—the rushing waterfall, the flapping gull, the gentle spring wind melting ice. Rural Iceland would have been a natural fit for Dan today if his ancestors hadn’t left there in the late 1800s.

This love for stimulating environments carries over to his work as a lawyer–and he can dish them out, too. He likes to spin jokes and colorful nicknames for Twin Cities law firms and opine about the influence GOD’S University has on society. (It stands for Geraldo, Oprah, Donahue and Sally, he says, beaming—the punch line of a joke.) He loves a verbal sparring match and often wears his emotions on his sleeve: his laughs, tears of sadness, love for children.

In 1937, his father Sidney founded what became Gislason & Hunter LLP, now a 102-employee law firm with offices in New Ulm, Minnetonka, Mankato, Mapleton and Des Moines. It was Dan and others who elevated the law firm higher than Sid’s dreams to become the largest law firm headquartered in outstate. Besides having been on the Governor’s Commission for Judicial Selection, Dan specializes in Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), in which he has been a pioneer, currently chairing the Minnesota Supreme Court’s Alternative Dispute Resolution board.

Rather than Iceland, these days he gets his fix gazing out his New Ulm office perch at the bald eagles, hawks, deer and turkey traversing the Cottonwood River bottomlands below. This private, backyard wildlife refuge behind the firm’s headquarters is much closer than Iceland—and it fits him just fine.

CONNECT: Have you been to Iceland?

GISLASON: My grandfather came from Iceland to America in 1878. In 1975, I went with my dad and mother to Iceland and it didn’t feel like home to us. The best words to describe our thoughts of the country came from my dad’s mouth: ‘I can understand why my father’s family left Iceland, but I can’t understand why it took them so long to do it.’

Iceland is a beautiful country, though. Go to their waterfalls: they are absolutely beautiful, with no fences surrounding them, no kiosks, and no warning signs. If you want to fall in the water, you can fall in. The falls are clean, pristine and natural.

But what impressed me most was its people. There hasn’t been much outside influence in Icelandic affairs over the centuries because it’s so isolated. Its people today can read what was written in Icelandic a thousand years ago. Their legislature is the longest continuously running one in the history of man. They have tried to retain their cultural heritage: for instance, when naming their children they still take their dad’s first name and then add ‘son’ or ‘daughter’ to it, like Gislason.

Even though they have strong ties to their cultural past, the country is also modern, with most Icelanders having a U.S. or European education.

CONNECT: How many employees does your law firm have? and where are your offices?

GISLASON: We have 15 lawyers in New Ulm, 16 in Minnetonka, 7 in Mankato, and one in Des Moines. Add up everyone, including lawyers, and we have 102 employees.

It takes seven years or more for an associate to be eligible as a partner. Every lawyer receives seven years of college education. They are all at the top of their high school and college class, and for the people we hire they are at the top of their law school classes. They are sharp, yet they still have much to learn—and a person never stops learning in this business. The law is always changing and there are always new approaches to the practice of law.

CONNECT: Do you prefer the term attorney or lawyer?

GISLASON: (Laughter.) I’ve always liked the word ‘lawyer.’ I see a lawyer as someone who takes off his coat, rolls up his sleeves, loosens his tie, and says, Let’s work. An attorney is one who wears a three-piece suit, a gold chain watch, and is stoic.

CONNECT: From your perspective, in what way does the average American view the legal profession?

GISLASON: I think Americans, in general, look at lawyers as a necessary evil. Certainly, lawyer jokes are funny and I know a few. My favorite one: Every lawyer is a jerk except mine. (Laughter.)

People realize that lawyers have a function in society. We are the ones to guide people through their troubles and we give order to legal tangles. Yet there is a certain aspect of the legal profession that people dislike—people dislike being sued.

CONNECT: If you could change your profession’s ethics, how would you go about doing it?

GISLASON: The ethical standards of the legal profession are exceptional and strictly enforced. Only a few lawyers try to push the envelope. However, if I could change anything, it wouldn’t necessarily be the attitudes of those few lawyers who push the envelope—it would be to change the attitudes of people who hire lawyers.

The driving force behind ‘pushing the envelope’ is the client’s wish to win, dominate, control or exert power. The client is fueling it with his or her pocketbook. One complaint of people fighting corporate America is that corporate America has an endless pot of gold to pay its lawyers. It’s also a strategy: fight until the other side has run out of money.

CONNECT: Law schools nationwide are producing more and more graduates. Has the Minnesota state bar discussed making the bar examination tougher to limit the number of lawyers?

GISLASON: Our state hasn’t done that. But my son took the bar in California, a state that has many more law schools than Minnesota, and California’s bar exam and grading is much more difficult than ours. In Minnesota, St. Thomas University opened a new law school after Hamline opened theirs. When I was in law school we had two law schools: the University of Minnesota Law School and the William Mitchell College of Law.

Are there too many lawyers? Sure. But the number of lawyers would be reduced if society changed its own attitudes. Lawyers don’t create business; their clients create it.

CONNECT: So you say the problem isn’t so much greedy lawyers, but greedy people.

GISLASON: Sure—and juries, courts and legislatures. Juries make many of the decisions. It wasn’t a lawyer who awarded a lady $32 million in the McDonald’s coffee cup case—it was a jury, one made up of independent and intelligent people like you and me. In addition to juries, the courts and legislatures have permitted the awards.

In the last 15 years, state and federal governments have been tougher on crime. We are building prisons like there is no tomorrow. But lawyers aren’t building those prisons. It’s our elected representatives who have been pressured by their constituents. As a consequence, we need more lawyers to prosecute and to defend those who are charged by law enforcement.

CONNECT: President Bush says he wants meaningful tort reform, and now with a Republican Congress we will likely see it. For our readers, could you define ‘tort’? Also, do we need tort reform?

GISLASON: A ‘tort’ is a wrong which one person commits against another. A well-known tort is that of a person negligently driving an automobile and hurting someone else. Another kind of tort is a ‘public nuisance,’ such as an outdoor rock music hall which affects a neighbor. Defamation is another type of wrong by one against another.

CONNECT: And it happens in medicine, too.

GISLASON: Yes, medical malpractice is a tort. Here’s the question our society needs to address: Have we gone too far with our tort system? The torts receiving the most attention right now in the media involve medical malpractice and punitive damages.

Our office does a lot of medical malpractice work on the defense side. For example, we represent the doctors who treated Viking Korey Stringer. The Stringer family is suing a number of people, including members of the medical profession, for negligently treating, protecting and caring for Korey Stringer before and after his hospital admittance. Korey Stringer was making millions annually as a professional football player. Now he is dead, so his family has lost that economic opportunity. The Stringer family would argue that if the doctors were at fault there should be no limits on what they can recover.

The medical profession, and those in favor of tort reform, would say that if we allow unlimited damage awards against doctors, society as a whole will pay.

The doctors are paying for the damage awards through their medical malpractice insurance premiums. If they don’t carry enough malpractice insurance, or if they have no insurance at all, the damage award must be paid from their own pockets. Ultimately, though, doctors will try to pass on the cost of a rising malpractice insurance premium to their patients. So we go in for a routine office visit, and the result is what we feel is an exorbitant charge for a routine exam, for instance. To keep medical costs down, doctors have to keep their costs down, the argument goes. For the doctors to keep their costs down the awards on medical malpractice must be limited.

So should awards be limited in medical malpractice cases? One could argue that if limitations are going to be put in place for this type of claim, then limitations should be placed on other claims involving injury or other damage. Why should doctors be protected and other wrongdoers not protected?

The opposing argument is that people who have sustained damages as a result of a negligent doctor should be fully compensated. They should not be called upon individually to ‘sacrifice’ in order to reduce the cost of medical care for others. Generally, the tort system is the vehicle with which monies are directed to compensate victims rather than through direct government aid from tax revenues.

So am I in favor of tort reform? I’m in favor of society continuing to use the tort system in a productive way for all segments of society. I am not in favor of what I would call ‘the me generation’ that was born in the ‘60s and has continued to grow, in which we primarily focus on the victim. We have taught people to be victims. That is not productive.

CONNECT: One of your specialties in law is alternative dispute resolution. Let’s say you brought the two sides together in this debate over tort reform—those wanting reform, those not wanting it. How would you bring them together through mediation, for instance?

GISLASON: The art or business of mediation is one of helping people make their own decisions. The buzz word in the field is ‘self-determination,’ as opposed to having a third person tell the two parties what they will be doing. Such could be the case if Congress tells them what will be happening.

Mediation involves two parties going to a third person, and using that third person to help them resolve the conflict themselves. In this particular case you’ve presented, it would involve trying to help both sides understand and recognize the others’ interests. Also, I would help each side realize that they probably are holding an unrealistic position. Extremism doesn’t work. They also would likely need to modify their own expectations in order to realize some of them—and then focus in on their most important interests.

CONNECT: Could you more fully define ‘alternative dispute resolution’?

GISLASON: It has many forms, but the two most common are arbitration and mediation, which are distinctly different. The ‘alternative’ word simply refers to an ‘alternative’ to going to court, where a judge or jury would decide a matter. With the type of ADR known as arbitration, the dispute is solely decided by a ‘rent-a-judge’, a third-person arbitrator or a panel of three arbitrators, with majority rules.

Mediation is very different. In that process the mediator doesn’t decide anything, but rather the people decide. For example: In family law, where there are child custody issues, instead of a judge telling parents the fate of their children, a mediator helps the parents make the decision themselves. In mediation, a third person can impose the process; but they can’t impose the decision.

CONNECT: Is your firm the largest based in outstate Minnesota?

GISLASON: We see ourselves as that. We do have 16 lawyers in our Minnetonka office, which you could argue is not outstate, but much of their work is outstate. That office wasn’t opened until 1980, years after we opened our New Ulm office. My father settled in New Ulm in 1935.

CONNECT: Why practice ADR? Doesn’t it in reality hurt your business, because you’re not sending your clients through costly negotiations and court proceedings?

GISLASON: I gave a speech to the state bar association six years ago in which I said that if ADR is as successful as I thought it would be, that we would have to close one of our law schools in Minnesota because of a diminishing need for lawyers. Instead, St. Thomas is starting a new law school. Now I don’t know if St. Thomas’ purpose in starting a new law school is to develop trial lawyers, which is really what we’re talking about. But what I see happening is the opposite of what I was predicting six years ago.

My concern about ADR is from a litigant and trial lawyer standpoint. Because of it, in another 20 years we likely are not going to have many truly trained and experienced trial lawyers. So few will have actually tried a lawsuit. Most will have been settled using ADR. In order for us to have good trial lawyers in 20 years, our lawyers will have to try scores of lawsuits to a conclusion in front of a jury between now and then.

CONNECT: Aren’t less than 5 percent of all lawsuits taken to trial?

GISLASON: Right. Lawsuits ending in a trial are becoming rarer. And, like I said, this is a drawback of ADR: it limits the opportunities for young lawyers to try lawsuits.

Yet, it’s not all gloomy. When using mediation, much of that process involves using skills that are also used for a trial, such as taking oral depositions. The same mental processes are involved.

On the other hand, most people who have disputes don’t want to go to court. They want a quick, easy, inexpensive resolution. In the corporate world, where a company may have an ongoing business relationship with their disputants, mediation can maintain a business relationship. A corporation and a vendor may have a fight over quality of a product. The lawyers first reaction is to sue. But the businessman’s first reaction is to resolve the dispute with the vendor because generally the vendor makes a good product at a good price.

CONNECT: In other words, the business needs the vendor.

GISLASON: The mediation process can help resolve those disputes early and cheaply, and help maintain business relationships without the confrontational atmosphere of a court room. Mediation can be a strong tool for business. It’s not used much, but as executives become more and more familiar with it, they are going to be directing their house counsel to follow that process early on.

CONNECT: You built your business on insurance defense work. What has happened to that side of the business in the last 20 years?

GISLASON: It has decreased significantly in the New Ulm office, but it has increased in the Minnetonka office. Some of it is our own doing because we have de-emphasized that part of our practice in order to work on the business side of lawyering, particularly ag business. Also, many insurance companies are now choosing to use their own lawyers as opposed to using outside counsel. And there isn’t nearly the product liability litigation today that there was 20 years ago because—as a result of all that litigation—products have become safer. Businesses are doing a better job of teaching their customers how to use products safely. The result is that fewer people are getting hurt, resulting in few lawsuits. The process has worked.

We would still have dangerous cars today, and we would still have flammable fabrics on childrens’ clothing…

CONNECT: …If it hadn’t been for Ralph Nader? (Laughter.)

GISLASON: (Laughter.) No, if it hadn’t been for the legal profession as a whole. (Laughter.) Ralph Nader certainly was a part of it. But if it hadn’t been for lawyers taking a risk society wouldn’t have had as many of the positive changes that it has had.

Congress and state legislatures often protect powerful special interests. And it may be that when there is a need for reform, the people in power may not be in favor of it. On the other hand, the legal profession, through the tort system, allows anyone to get into a courtroom to make their case to effect change.

The judicial system can be a safety net for people. In years past, nobody much cared about people with disabilities because most of us aren’t disabled. Many laws favoring people with disabilities came about as a result of courtroom litigation rather than legislation.

CONNECT: So you’re saying that your profession is a ‘checks and balances’ on the system?

GISLASON: Absolutely, and that’s why we need a strong court system. The system works, and it has worked.

CONNECT: I’ve heard that the number of personal injury litigations rises when the economy falls. Why is that?

GISLASON: I’d be interested to know whether the number of lottery tickets purchased also rises when the economy falls. My guess is it does. When people are short on cash, often they look for a way to make up their shortfall. When they are flush with cash they don’t have the same need.

CONNECT: So would you advise businesspeople in a sputtering economy to be more careful in doing business?

GISLASON: Yes, and I would certainly advise them to resolve disputes early on. That sort of approach does not do well for the legal profession, but it certainly does well for business. If you feel that your adversary is going to be more litigious because of the economy, one way to defend against the cost of the litigation is to resolve the dispute early. My way of doing it is through mediation. Another way is for the CEO to call up the other CEO.

CONNECT: Could you explain joint and several liability?

GISLASON: It’s a rule of law premised on the concept of who should bear loss. The principle behind it is this: imagine that an innocent person has been harmed at no fault of their own and the harm was caused by two or more entities. One of the entities has money and the other doesn’t. Imagine in this case that the primary person at fault is the one without any money. Then who should suffer? The person who was less at fault, yet who was still at fault, or the victim?

Here’s an example: Say we have a person who was a passenger in an automobile wreck. The passenger wasn’t at fault. The driver of the car in which the passenger was riding had the right-of-way and also had a million dollars worth of insurance coverage. The person who caused the wreck by recklessly driving through a yield sign, imagine that this person was uninsured.

There was likely some fault on the person who had the right-of-way because he may not have been cautious enough. So let’s assume the person with the right-of-way is 10 percent at fault. This is minor in comparison. Should that 10 percent-at-fault person pay for all the damages of the innocent passenger who can’t be compensated by the person who failed to yield? Or should the passenger just suffer by not being compensated for his or her expenses and injuries?

In essence, our state has said through its joint and several liability laws that it doesn’t want the innocent passenger to suffer. So the driver at 10 percent fault will have to pay more than his fair share—and suffer himself. But as a society we’re not that worried about the driver who has to pay because we presume that he has insurance to pay for it, and we presume the cost will be absorbed by all the policyholders of that particular insurance company.

But that might not be true. Suppose the driver has only $50,000 worth of insurance coverage, but he has a $1 million net worth with his farm or business. And suppose he has to sell the farm or business to pay the passenger. This is when joint and several liability becomes very difficult for society to swallow, because now two innocent people are victims.

The question we need to answer is how to balance the rights of both innocents: the passenger and the driver. It will be talked over in the new Pawlenty Administration. Right now in Minnesota we have a law that if the person with the right-of-way is 15 percent at fault or less, the maximum they have to pay is four times their percentage of fault. So if he’s 10 percent at fault, the most he has to pay is 40 percent of the settlement. In our state there are already some limitations placed on joint and several liability.

CONNECT: What would you say to those people who would like to take the percentage up to 51 percent before they have to pay?

GISLASON: I’m sort of a Rockefeller Republican. As a society we need to continue to take care of innocent people who have been damaged.

The tornado in St. Peter is one example of that happening. Our society decided years ago, through FEMA, that it was going to help people in natural disasters who cannot recover because they lack sufficient insurance. In our society we have found a way to take care of those people. If we eliminate joint and several liability, I believe we then have to supplement it with another form of protection—or safety net—for those innocents who have been damaged or hurt and don’t have a means to cover their costs. If we decide on an alternative way of protecting innocents, then maybe joint and several liability should be further modified.

CONNECT: How would you describe the culture of your law firm?

GISLASON: Ours is one of ‘modified egalitarianism,’ where we focus on collegiality and on being partners, and on everybody working for the good of the whole. We all work for the good of the entire firm as opposed to lawyers who work for firms where the culture is ‘eat what you kill.’ In the ‘eat what you kill’ culture’ often you have a group of individuals who jealously protect their own turf, who see each other only morning and night, and simply share the costs of administration and office space.

We are different. We started in New Ulm. The lawyers here spent a lot of money to help open our Minnetonka office. And those Minnetonka lawyers, plus the ones in New Ulm, spent a lot of their own money to open a Mankato office. We reduced our income in order to do that, to enable the firm to grow in numbers and in practice areas.

Our organizational style also enables us to do a lot of pro bono work. Instead of having an individual lawyer suffer by not bringing in income in doing pro bono work, we assist them by sharing in the cost. The other part of our culture is to be honest. We can walk into almost any state courtroom, I believe, and have the respect of the court and the opposing counsel because of our name. We work hard at our reputation. We try not to push the envelope. We don’t try to be the meanest lawyers in town—and yet we are strong advocates for our clients. But we advocate fairly.

CONNECT: What of your involvement in the community?

GISLASON: My recent role in New Ulm has been teaching the Parents Forever class that originates with the court system. Most of my past community work has been through the court system as well. I’m also with the New Ulm Economic Development Authority. On a state level, I’m the chair of the Supreme Court’s Alternative Dispute Resolution Board. That body is made up of judges, lawyers, court administrators and a liaison from the Minnesota Supreme Court. We write the rules and the code of ethics for ADR for the Minnesota Supreme Court—and we enforce the code of ethics and regulate who is qualified to be an ADR neutral. I’ve been spending the last eight years helping give birth to this process on a statewide basis.

CONNECT: Finally, your opinion of Arne Carlson, who spoke at one of your law seminars a few years ago?

GISLASON: From a lawyer’s standpoint, Arne Carlson is an incredible man.

I was on the Governor’s Commission for Judicial Selection, and as a result was partly responsible for recommending to the governor many of the men and women who are now judges in this district.

Arne Carlson resurrected the process of this form of judicial selection and supported its development. Governor Perpich had basically disregarded our recommendations; he named whoever he wanted. The person first in charge of that commission was Paul Anderson, who is now on the Minnesota Supreme Court and is a marvelous Justice from the standpoint of teaching children about the judiciary and the law.

During his eight years in office, Arne Carlson chose all but one of his district court judge appointments from the list of three given to him by us. Those final three were recommended on a nonpolitical, merit basis. We have an incredible judiciary now because of that process, and fortunately Governor Ventura, who didn’t know about judicial appointments when he was elected, also followed the process. He conducted his own interviews. Kurt Johnson, who used to be a partner here, interviewed with Governor Ventura and was selected.

GET TO KNOW: John Linder

Born: October 1953.

High School: Wilson School, Mankato, ‘72.

College Education: Attended Mankato State, U. of Minnesota, and Louisiana State. One-year program at Dunwoody Institute in electronics.

Board Memberships: Community Bank (Vernon Center, Amboy, Mankato); Minnesota Valley Broadcasting (CEO); Minnesota Electric Supply.

Trade Memberships: National Broadcasters Association; Minnesota Broadcasters Association.

© 2003 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.