European Roastarie

Photo by Kris Kathmann

The Kenya Airways pilot dips his left wing as if to prod Timothy Tulloch into appreciating the vast plains of Tsavo, and beyond, the snow-clad Mt. Kilimanjaro. Nairobi is fifteen minutes yet. The earth below is a lush paradise of cheetah, Maasai villages and elephant herds. The seat belt light above him flashes. Mt. Kilimanjaro appears out his window.

The passengers on Tulloch’s flight from London are cut from United Nations cloth: an American here, quite a few East Africans there, the boisterous Aussie, a Swedish couple, a trade delegation from Taiwan, and the Koreans.

Seeing them, Tulloch chuckles at a thought. He was born a Highland Scot, went to college in England, worked on his thesis in Nepal, once lived in Zaire, has a business in Le Center, Minnesota, and buys coffee beans in Kenya—this week, at least. He fits quite nicely into this flying melting pot. Next week means Indonesia, and another coffee plantation.

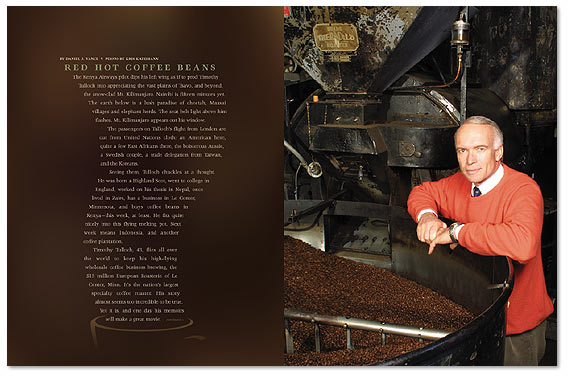

Timothy Tulloch, 43, flies all over the world to keep his high-flying wholesale coffee business brewing, the $15 million European Roasterie of Le Center, Minn. It’s the nation’s largest specialty coffee roaster. His story almost seems too incredible to be true. Yet it is, and one day his memoirs will make a great movie.

Tulloch’s coffee career began percolating in 1979

Flying Nairobi to London as a 20-year-old college student, Tulloch remarked to the gentleman next seat how poor the in-flight coffee tasted. It was rank. The two began a crisp dialogue, and Tulloch learned the man worked for Swiss coffee giant EDM Schluter. By the time their jet had landed, Tulloch had landed himself a job. He would be a “cupper” for Schluter in Kenya, but under two conditions: he had to learn French; and in three weeks time he had to learn how to fly an airplane.

“I’d been in Kenya studying the introduction of coffee as a cash crop for my thesis at university,” he says with a proper English accent. “I’d also been in the Philippines studying rice, and in India and Nepal.” His degree would be in Agricultural Economics.

So he took the job of “cupper.” “Every week there was an auction of all the countryside coffee,” he says. “I would roast, evaluate, and rate the quality of each coffee before the auction, about 200 varieties. I would then inform roasters worldwide of my decisions and thoughts on the prices that it should go for at auction.” Afterwards, he would arrange for shipment to Mombasa, Kenya, and on to Scandinavia, Germany or the U.S.

At that time the U.S. specialty coffee market was in its infancy, confined mostly to retail coffee shops on the coasts attracting diehard drinkers. “The specialty coffee market was really born in the late ‘70s by entrepreneurs who went to countries of origin, to the plantations, to ask them to put extra preparation into handpicking and handsorting their coffee,” he says. As a result, great coffee began flowing to the U.S., especially to the West Coast, and ultimately what had been a mocha trickle became a rich flood of Starbucks and Caribou Coffees.

EDM Schluter transferred Tulloch from Kenya to Zaire and into the gastrointestinal problems of darkest Africa. Zaire was governed by one Mobutu Seko Seko, a corrupt and delightfully cruel dictator who later would flee. (Zaire is now the Republic of Congo.) Tulloch did more of the same for Schluter there over five years: he flew an airplane, visited plantations, bid on coffee, and arranged for exportation and transportation. His employer was the largest green coffee exporter in East Africa.

“Then I met a delightful Peace Corps girl there from Minnesota,” he says. “Therese was teaching English as a second language. My pick up line to her was, ‘I have the only bath in town.’ In three weeks she turned up needing a hot bath, which was prepared by lighting a fire under a 44-gallon drum of water.”

He stayed on in Zaire with Therese, who would become his wife, until it seemed Mobutu was losing control. (The dictator lasted until 1997.) Mobutu had become lavishly rich and in the process had starved millions of Africans. It was becoming “unpleasant” for Tulloch to work there, not to mention raise a family.

So he and Therese made a nest in Minnesota. They purchased a farm house on rolling country between Montgomery and New Prague. Therese had been raised in Minneapolis, but Tulloch also had business on his mind when choosing the United States and Minnesota. “I never could have started a business like mine in Europe,” he claims. “In Europe all the monuments have already been put up. Business relationships are well established—sometimes going back hundreds of years. It’s very hard there to come in with a new business with an established product such as coffee.”

He adds, “In America, if you do what you say you’re going to do, and if you provide service, and you’re the best, and you dedicate yourself, you can develop a niche. There are sectors that have been overlooked by the Big Boys. As they say, elephants leave big spaces. And you can get underneath them.”

So what would he do? “All I knew was coffee,” he says. “So I started a coffee business. I had enough savings to open one retail store. I called it ‘Regency Coffee.’ (It was in the Hyatt Regency, Minneapolis.) People told me that no one would pay a dollar for a cup. They gave me three months before folding.”

His detractors would be proven wrong. Tulloch built Regency Coffee into 11 outlets before selling in 1991. (Many of his former stores are now Starbucks and Caribou Coffees.)

From there the plan was to transition into wholesale, which had potential for growth. As a wholesaler, he believed he could buy green coffee from around the globe, ship it to Minnesota, roast and package it on his farm, and sell to retail outlets. His competitive advantage would be “freshness,” because he knew his competitors-to-be were roasting and shipping from the coasts. Their product couldn’t be as fresh. Within the year European Roasterie was born on his farm in a hut that had a dirt floor. Initially, he did all the roasting, delivery and collection. Ultimately, he moved off the farm in 2000 and into a Le Center building where today he has about 50 employees.

And there he learned to delegate. “There are people better than me at administration, marketing, and dealing with customers,” he says. “I had to let it go.”

Not your typical manager, he believes people should be treated equally inside the business, which means it can’t be below even the owner to sweep floors on occasion. “If we are equal outside the business,” he says, “everyone should be equal inside. There shouldn’t be a hierarchy. My role is to make sure people work as a team, and treat each other as customers, not competitors. We all work together for the same objective. We have a laid-back atmosphere.”

Today, European Roasterie has 2,000 customers in 50 states, primarily independent coffee shops, white-table restaurants (such as The Country Pub in Kasota and Chianti’s in Mankato) and upscale supermarkets. Because his company was one of the first dedicated solely to specialty, Tulloch got in on the ground floor. Now more than 3.2 million pounds of coffee pass through its doors annually. Sales are $15 million, and climbing, with private label packing an important segment. Look for these labels in a coffee shop or grocery near you: Boardwalk, Fleming, Cameroon, Regency, Santa Fe, Florida’s Best, Steaming Bean, Fredericksburg Coffee, Fair Trade, Perfect Cup, Majestic, Berry, and Marcels.

The seed for making coffee king was planted during World War I when the U.S. military inserted packages of coffee inside daily food rations for soldiers.

After World War II a handful of national coffee manufacturers popularized coffee drinking further by placing it in tins—and then advertising the heck out of it. “For companies like Maxwell House to get the coffee into the tin they had to roast it first,” he says, “and then de-gas it for five days so the coffee would stop roasting and not explode when placed in the tin. Due primarily to the advertising, people were sold on Maxwell House, Folger’s, Eight O’Clock and Nestle. Before WW II the U.S. had a great number of independent roasters, and they all went out of business because they couldn’t compete with the popularity of tin coffee.”

New technology, i.e., the tin, had helped national manufacturers in the 1950s. But new technology would hurt the manufacturers beginning in 1986, when an ingenious inventor came up with the “one-way valve,” which made it possible for a smaller company to roast coffee and instantly place it hot inside a flexible plastic bag without later having the bag explode from gas buildup. A revolutionary invention, it turned the coffee industry on its head. Consumers could then buy fresher coffee.

The national manufacturers were caught with their pants down, but none realized it—at least right away. Meanwhile, specialty coffee stores sprang up. Millions of Americans began drinking better-tasting coffee. They spread the news. Demand for specialty coffee increased as home coffeemakers multiplied. Business executives began having “nonalcoholic” meetings in coffee shops, shying away from politically incorrect bars. It was a cultural shift.

“The first meeting of the Specialty Coffee Association of America was 1988,” he says. “There were 60 of us. Now we have 8,000.”

Maxwell House, Folger’s and Nestle are “The Big Boys,” he says, and right below them are 25 or so specialty roasters, of which European Roasterie is largest. And below the specialty roasters are “boutique roasters,” the one-outlet shops. These boutiques certainly generate aroma and create ambiance for their coffee-drinking customers, but they simply aren’t able to brew consistent cups of coffee.

Not surprisingly, the Big Boys fought back. “At first we just irritated them,” Tulloch says. “Then we annoyed them. Then they started buying small, family-owned roasters. They have approached us. The moment the Big Boys take over a small roasting company it’s usually the end. They close it down and transfer buying to a central office. The decisions, and quality, are then determined by accountants.”

He likens the war with the Big Boys to Drake’s confrontation with the Spanish Armada in 1588, when a smaller, more agile English navy outmaneuvered the bulky Spanish fleet. “Business is a battle,” he says. “You never know what each day will bring.”

And it’s a war he could win. The national coffee “armada,” both retail and wholesale, so far hasn’t touched the fund-raising industry, where Tulloch sees potential for specialty coffee sales. (Why couldn’t the Girl Scouts sell European Roasterie coffee?) Another growth area: the Starbucks and Caribou Coffees of the world won’t touch towns of less than 12,000. Towns between 2,000 and 12,000 can support an independent retailer, he says, and someone must supply them. Tulloch has eyes on that burgeoning market.

Raiders Of The Lost Cup

While in Zaire, Tulloch had the notoriety of being the first person in the coffee exportation business to have an entire trainload of coffee stolen.

“The train just disappeared off the face of the earth,” he says of his 1982 nightmare. “Some coffee was found in Zambia, Malawi and Zimbabwe. Someone had stolen the entire train—engines, cars and all. It was worth many millions. At that time coffee was four dollars a pound. When Lloyd’s of London learned of it, they rang the bell, something they normally only do when a merchant ship sinks.”

Latte Terrorism Around

In his own way, Tulloch is striking back at terrorism—and slowing illegal immigration.

He says, “Since September 11 especially, there has been a need for us Americans to be fair in our trade practices with third world countries. This way we can cut off the recruits, so to speak, the people who want to do us damage.”

As for illegal immigrants, the U.S. has eight million, with a good percentage being Central Americans looking for a better life. Central American coffee farms have been going out of business due to low coffee prices. Tulloch believes “fair prices” paid for coffee beans, which would allow for “fair wages” to plantation employees, could keep many immigrants home.

“So now in our industry we have ‘fair trade’ coffees, which have been developed by roasters like us who pay a fair price, and who deal with people that pay a fair wage.”

Whining Mocha Malcontents

The medical profession has been trying to find “something” wrong with coffee, Tulloch says. “Initially they thought it was bad for pregnant ladies. But it ended up not having an effect. The health benefits of drinking a couple cups of coffee daily are enormous in terms of it being anti-carcinogenic, good for the digestive system, and good for general health and well-being. So the jury is in, and coffee is Not Guilty. The medical profession tries to find something wrong with everything that is good about our lives.”

Buying The Best Brew

Timothy Tulloch, owner of European Roasterie, might remind more than a few aging Americans of the erudite Mr. French, the English butler of the 1970’s “Family Affair” TV series. He seems proper and particular about his ways—and he needs to be. His expert taste buds and buying expertise are crucial to the success of the operation.

Coffee, he says, is much like wine. A Colombian coffee differs from a Sumatran which differs from a Kenyan. Some plantations do a better job at preparing coffee than others, and others have better soil qualities or are in superior microclimates. The trick is to find the best plantations in any given country.

The Big Boys normally don’t buy the best lots because of expense and limited availability. Smaller roasters, like European Roasterie, buy the top two percent in quality of a plantation’s production.

“I seek out coffees around the world,” he says. “I go on buying trips three months a year to Mexico, Panama, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica, Belize, Columbia. Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Indonesia, Sumatra, Papua New Guinea, and Hawaii, up into the mountains to visit plantations and cooperatives.”

But he doesn’t buy just anything—or from anyone. He wants coffee from growers who “satisfy his conscience,” which means no child labor, no erosion, no pollution, and a fair wage, medical care and perhaps schooling for plantation employees or their families.

He explains, “You get pollution when you wash, ferment and clean the ‘cherries’ to prepare them for export. There is a great deal of water used. Traditionally that very acidic water has gone into rivers. I also don’t do business with people who kiln dry beans because that requires wood, which can decimate forests.”

Before roasting, every green coffee purchase is sampled five times: at the plantation; before shipping; at U.S. Customs; upon arrival in Le Center; and finally, immediately before roasting in order to fine-tune roast times, air flows and temperatures.

“Coffee has been switched on me before arrival,” he says of coffee bought from one Indonesian plantation. “I won’t do business with people who do that. It ended up arriving delayed, and was moldy. So I rejected it.”

© 2003 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Great reading . I was looking for past emplees of Edm Schluter & Co. Ltd both in Africa and London where I worked during 1949 and 1958, possibly not the same company but very interesting.

As a new small batch roaster I really enjoyed your insight and guidance regarding FTO movement around the globe. I endorse Fair Trade practices and look forward to making my contribution as our small family roastery grows. Thanks.