Beemer Well Drilling

Fourth-generation Fairmont small business laying groundwork for fifth.

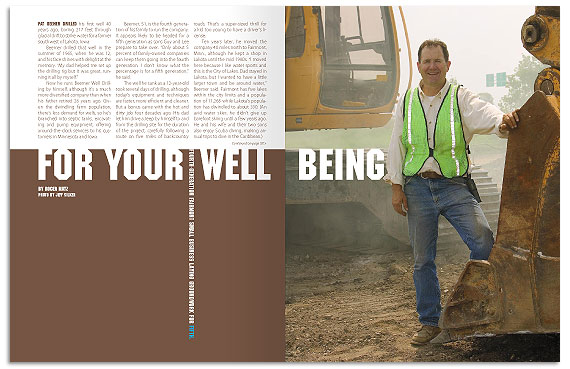

Photo by Jeff Silker

Pat Beemer drilled his first well 40 years ago, boring 217 feet through glacial drift to strike water for a farmer southwest of Lakota, Iowa.

Beemer drilled that well in the summer of 1965, when he was 12, and his face shines with delight at the memory. “My dad helped me set up the drilling rig but it was great, running it all by myself.”

Now he runs Beemer Well Drilling by himself, although it’s a much more diversified company than when his father retired 26 years ago. Given the dwindling farm population, there’s less demand for wells, so he’s branched into septic tanks, excavating and pump equipment, offering around-the-clock services to his customers in Minnesota and Iowa.

Beemer, 51, is the fourth generation of his family to run the company. It appears likely to be headed for a fifth generation as sons Guy and Lee prepare to take over. “Only about 5 percent of family-owned companies can keep them going into the fourth generation. I don’t know what the percentage is for a fifth generation,” he said.

The well he sank as a 12-year-old took several days of drilling, although today’s equipment and techniques are faster, more efficient and cleaner. But a bonus came with the hot and dirty job four decades ago. His dad let him drive a Jeep by himself to and from the drilling site for the duration of the project, carefully following a route on five miles of backcountry roads. That’s a super-sized thrill for a kid too young to have a driver’s license.

Ten years later, he moved the company 40 miles north to Fairmont, Minn., although he kept a shop in Lakota until the mid 1980s. “I moved here because I like water sports and this is the City of Lakes. Dad stayed in Lakota, but I wanted to have a little larger town and be around water,” Beemer said. Fairmont has five lakes within the city limits and a population of 11,265 while Lakota’s population has dwindled to about 330. (An avid water skier, he didn’t give up barefoot skiing until a few years ago. He and his wife and their two sons also enjoy Scuba diving, making annual trips to dive in the Caribbean.)

By 1974, Beemer had graduated from a junior college in Iowa Falls and served a two-year hitch as an Army draftee. He returned to Lakota in the summer of 1974 and resumed drilling with his father. “I spent most that summer drilling in the Fairmont area and I saw the opportunities up here,” he said.

That fall, he serviced a well pump on an acreage north of Fairmont and “ended up buying the place.” The heavily wooded 23-acre site along Interstate 90 included a peninsula stretching into Buffalo Lake, where he and his wife, Jackie, built a home in 1989. The old farmhouse where they first lived serves as a two-story showroom for Jackie’s antique business, the Buffalo Lake Peddler. Nearby is a large steel building that’s the headquarters and main shop for Beemer Well Drilling. Jackie has furnished his office with a variety of antiques, including an S-curved, roll top desk and the oak cabinets that once displayed merchandise in a Ceylon hardware store.

Beemer’s drill business peaked in 1978, when severe drought gripped the region. The company drilled 365 wells that year, most of them replacements for wells too shallow to reach shrinking aquifers. Most of those wells reached down only 40 to 60 feet, and were replaced by shafts sinking 125 to 165 feet.

“We never matched that volume again,” Beemer said. Before the 1978 peak, Beemer averaged 100 to 120 wells annually. “Today, it’s around 50 to 60,” he estimates. The downward slide began during the farm crisis of the early 1980s, when farmland prices collapsed, shrinking from highs of $4,000 per acre to lows of $1,200. (Twenty years later, it’s recovered to about $3,500 per acre, he said.)

Beemer responded to the economic downturn by buying a pump company in nearby Truman in 1983. “Because of this slow time, I realized we had to diversify,” he said. Before, he’d just drilled the wells and left the installation of pumping equipment to others. In 1983, pump sales, installation and service became in integral part of his business.

About the same time, he began offering commercial snowplowing services to Fairmont businesses and industry “because we had a backhoe and a dump truck with a plow on it. At one time, we had about eight trucks pushing snow.”

Beemer branched into construction-style activities “to keep our payloaders busy,” excavating for house basements and pits beneath the swine confinement buildings that were springing up around the county in the late 80s and 90s. He also added major tiling work for Martin County, grove and site removal and septic tank installation and pumping service to his product mix.

“Out here on the prairie, you have to be diversified or pack your suitcase and travel a multi-state area (if you want to do nothing but drill wells),” Beemer said. “Agribusiness is the major, driving force out here, but the tendency of people to migrate to five-acre home sites in the country enhances our business.”

Well drilling remains at the core of Beemer’s business, along with around-the-clock service for pumping equipment and septic tanks. He gave up snowplowing after five or six years, becoming too busy with 24-7 service calls on pumping equipment and septic tanks.

About half the wells Beemer drills these days are agricultural and half for lakeshore homes or residential homes on acreages. Many of the ag wells serve livestock operations, which require frequent maintenance, but the residential wells are low maintenance.

One factor contributing to the decline in the number of wells drilled is that some are part of mini-systems serving multiple housing sites. “We just finished two lakeshore wells, one that serves 14 lots and one that serves 26 lots,” Beemer said.

What hasn’t changed is the satisfaction that comes from bringing in a well and producing a fresh stream of water. “It’s quite rewarding to pump water that God has given us. It’s a thrill to produce, something like a farmer producing a crop. But we don’t make water, we just drill down to it,” he said.

Agricultural tiling, according to Beemer, has hurt shallow aquifers within five to 50 feet of the surface. “But the aquifers we’ve used since 1978, which are deeper than 50 feet, haven’t changed noticeably, even through periods of drought,” he said. The majority of wells he puts in today go down 150 to 250 feet.

Aquifers are distributed fairly evenly across the landscape at varying depths and Beemer says he has a 98 percent success rate in striking water. But there are localities where it’s not easy. To the west, around Jackson and Worthington, there are fewer aquifers and some are 500 to 600 feet down. In the Trimont area, northwest of Fairmont, the bedrock tends to be quartzite, a red igneous rock that’s harder than granite. There are no cracks or fissures where water can collect in this kind of bedrock, according to Beemer.

In the late 1970s, Beemer hit several dry holes on a Trimont farm, then called in a hydrologist who found an aquifer about a quarter of a mile from the farmstead. There he found good water at 256 feet. Four or five years later, a nearby farmer spent $25,000 for an 800-foot dry hole on his farmstead. But when Beemer moved his rig close to the good well he’d drilled a few years earlier, he hit water at 250 feet and created a mini-system for the farmer and three neighbors.

He sees rural water systems, financed by federal grants, as becoming more common in the future. “In 25 years, a good share of the wells will be for such systems,” he predicted. Since these systems are tested continually, “this guarantees the quality and drinkability of the water. Owners of individual wells sometimes don’t test their water as often as they should.”

Another advantage of system wells is the ability to be choosy about exactly where to drill. “We can go out and canvas a 20- to 30-mile area through geological surveys. We can find water that’s low in iron and hardness and then pipe it to more difficult areas,” Beemer said.

Beyond putting in more systems than individual wells, and finding more ways to diversify, what’s in the company’s future? “My son, Guy, could tell you. I’m happy just the way it is, but that’s pretty non-progressive. The next generation (of Beemers) will take it to the next level,” he said.

Beemer’s great-grandfather, John P. Booher, started the company in Nevada, Iowa, and moved it north to Lakota. Booher’s daughter, Mary, married Guy Beemer, his grandfather. Guy turned the company over to his two sons, Bob and Bill Beemer. Bob is Pat’s father. Bob and Bill split their partnership in 1975. Bill moved to Webster City, Iowa, and still runs a well drilling business there. Bob retired and lives in Spirit Lake, Iowa.

Beemer began buying out his father in 1975, completing the purchase in 1982. Now he’s approaching that crossroads with his sons and looks forward to having them in the business. Although multi-generation family companies are rare, they tend to be more common among well drillers, according to Beemer. “Maybe it’s just a coincidence, but there’s some driving force out here with our breed in drilling. There’s not a whole lot of drillers and pump installers per capita and it’s kind of a different niche. Pumping water out of the ground is quite rewarding.”

“Guy and Lee grew up with our business. They didn’t drill quite so early as me, but they’ve been on drilling rigs since they were 17 or 18. They were helping with snow removal, running payloaders, when they were 12 or 14 years old. They’ve been running pump trucks since they got driver’s licenses,” Beemer said.

Guy, 25, just graduated from Minnesota State University in Mankato with a degree in construction management. Lee, 23, is about 18 months away from finishing the same program. “They can see more than just well drilling as we’ve diversified. That’s what spurred them to go into construction management,” Beemer said. “They’ll be able to handle more work with fewer full-time employees.”

To Beemer, construction means projects like basements, pits for hog confinement buildings, tiling projects and septic tanks. But he admits there’s been little expansion recently in confinement operations so he feels that the “hog pits are gone. You have to be like a chameleon and change, adapt and possibly move. One of my sons may have to look elsewhere for another community, maybe to Mankato, because the prairie just doesn’t have the density of population anymore.”

Beemer doesn’t need to read population statistics to know there are fewer and fewer people living in rural areas. He can gauge it just by the lack of traffic on rural roads. “When we went to work, we used to run into tractors all the time, pulling four-bottom plows or six-bottoms. Now, when we occasionally run into a tractor, it’s probably pulling a plow that’s 26 feet wide and you’d better get out of the way,” he said.’

He seems at peace with himself, taking life as it is, relishing the diversity of his outdoor job, working beside employees who also enjoy being outdoors. “It’s hard to find the kind of person who’s willing to go out when it’s below zero and work on wells and repair water pumps. It’s a not-so-pleasant job sometimes, but then there are those warm beautiful mornings that make it all worthwhile,” he said.

Besides Beemer and his wife, the company employs eight people. “My employees are fantastic. They all have outdoor, farming backgrounds and they’re very talented.”

He’s hoping his job will change as his sons join the company. “I like the hard work part of it, but I’m getting tired of the bookwork part. I’d like to do more labor and let my boys do the computer work,” he said.

He believes moving the company to Fairmont was a good decision. “I don’t want to sound anti-progress, but there’s a quality of life here, without the hustle and bustle. Fairmont’s still got that small town touch.”

Well-ness Makes Health

It’s getting cleaner in the country.

That’s due to a plethora of environmental regulations enacted to improve water quality, according to Pat Beemer of Beemer Well Drilling, Inc., of Fairmont.

While some may criticize the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and the Environmental Protection Agency for over-regulating, Beemer isn’t among them. “Environmental regulations have helped my business as well as the products and services that customers receive,” Beemer said.

“These regulations require very accurate documentation of wells and septic construction, which is extremely valuable if future trouble-shooting of these systems becomes necessary. This documentation becomes public record, available to the customers and future owners of the property,” he said. “In the past, drillers kept all this information in their heads and it wasn’t available to others. That could lead to a ‘wild goose chase’ for future owners because everything drillers and septic tank installers do is buried when they finish a project.”

Along with drilling wells, Beemer’s company installs septic tanks, lays tile lines and excavates for a variety of projects ranging from homes to pits beneath swine confinement buildings. Relying on guidance from state and federal agencies, Beemer said “we’re working smarter. We’re treating raw sewage and not dumping it into creeks or field tile—and that used to be the case.”

Expertise available through environmental agencies and the University of Minnesota has made septic systems more efficient and reliable, Beemer said. “We have people with PhD’s teaching us how septic systems should work for proper treatment of effluent. Regulations mandate that we design systems according to a particular site’s type of soil so that it’s most effective,” he said.

Years ago and before regulations were enacted, there wasn’t much sharing of information. “Grandpa dug the tank and put it in, and never had the chance to talk to other people over the back fence about how they did it,” Beemer said.

Septic tank installers must be licensed by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, with certification training provided by the university. Continued training is required to maintain these licenses, according to Beemer. Consumers have benefited from a combination of regulations, better-qualified installers and improved materials and products, Beemer said.

Sometimes raw sewage still slips into creeks and tile, but “we’re turning the corner. We’re starting to make an impact with buffer zones that reduce siltation, slowing down run-off so pollutants can settle out,” he said. “Taxpayers are finally benefiting from set-aside acres that create these buffer zones. Out in rural areas, we’re doing a better job because we have the space that allows for buffer zones.”

What’s It All About, Algae?

Although Fairmont’s five lakes are still afflicted by algae “blooms” during summers, Beemer believes fertilizer spread on city lawns causes much of that. Lawn chemicals enter the lakes through storm sewers and feed the algae. But Fairmont is “making an impact” on the problem by building retention ponds that trap run-off and let nutrients settle out before escaping into the lakes, according to Beemer.

Fairmont draws its entire water supply from the chain of five lakes, so quality of the lake water is critical to the community. Beemer worries about the vulnerability of that water supply. “What if a crop duster dumped in the lake? A couple of years we had aphids in the soybeans and the dusters were in here like flies,” he said.

The city’s only backup is a well drilled in the late 1980s, after the lakes fell to dangerously low levels because of a drought. Beemer provides maintenance service for the well, which is 360 feet deep.

© 2004 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.