St. Peter Woolen Mill and Mary Lue’s Yarn & Quilt Shop

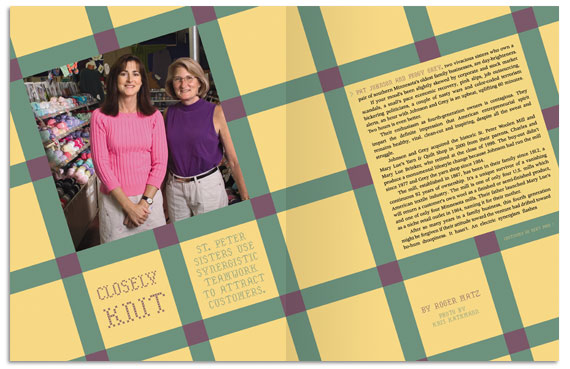

St. Peter sisters use synergistic teamwork to attract customers.

Photo by Kris Kathmann

Pat Johnson and Peggy Grey, two vivacious sisters who own a pair of southern Minnesota’s oldest family businesses, are day-brighteners.

If your mood’s been slightly skewed by corporate and stock market scandals, a snail’s pace economic recovery, pink slips, job outsourcing, bickering politicians, a couple of nasty wars and color-coded terrorism alerts, an hour with Johnson and Grey is an upbeat, uplifting 60 minutes. Two hours is even better.

Their enthusiasm as fourth-generation owners is contagious. They impart the definite impression that American entrepreneurial spirit remains healthy, vital, clean-cut and inspiring, despite all the sweat and struggle.

Johnson and Grey acquired the historic St. Peter Woolen Mill and Mary Lue’s Yarn & Quilt Shop in 2000 from their parents, Charles and Mary Lue Brinker, who retired at the close of 1999. The buy-out didn’t produce a monumental lifestyle change because Johnson had run the mill since 1977 and Grey the yarn shop since 1984.

The mill, established in 1867, has been in their family since 1912, a continuous 92 years of ownership. It’s a unique survivor of a vanishing American textile industry. The mill is one of only four U.S. mills which will return a customer’s own wool as a finished or semi-finished product, and one of only four Minnesota mills. Their father launched Mary Lue’s as a niche retail outlet in 1964, naming it for their mother.

After so many years in a family business, this fourth generation might be forgiven if their attitude toward the venture had drifted toward ho-hum droopiness. It hasn’t. An electric synergism flashes between the sisters as they finish each other’s sentences, talking about the past, the present and the future, their family tradition and their ingrained love of wool.

Ascending from employees to owners failed to significantly alter their attitude—or their daily grind. “We’d always run it as if we owned it. We cared about it. We took pride in it,” Johnson said. But she admits that when they assumed the mantle of ownership, “we found that our sense of pride increased.”

Ironically, the family could have taken an insurance settlement and quit after a tornado devastated St. Peter March 29, 1998. The shrieking winds ripped off the third floor and half the second story of their building, smashed the yarn shop, and scattered yarn and other inventory for miles. Because the mill equipment sat in the building’s first-floor interior, it was protected from serious battering, but drenched by torrential rain pouring into the roofless structure.

The process of cleaning up and returning the mill to operation took two frantic weeks. It might have taken much longer were it not for a building 11 blocks away that had been missed by the tornado. A year earlier, the family had installed machines in that building to manufacture a new line of mattress pads and quilts. “It had empty office space, so we picked up and moved there,” Johnson said. “We hooked up temporary phone lines and our computers. That’s where we operated for taking orders and shipping. We were able to continue the wholesale business.”

Meanwhile, at the mill itself, blue tarps stretched over what was left of the roof stopped the rain. Electricians wired in temporary electrical service and the wool-carding operation was back in business. But damage to the yarn shop was so extensive it stayed closed for 2 1/2 months. It was an exhausting, excruciating period for the family. “Our parents were ready to retire, so they left the decision about re-opening the mill and yarn shop to Peggy and me,” Johnson said.

There was little agony in reaching a decision. “When we were cleaning up after the tornado, people stopped by and said they hoped we weren’t closing. But we weren’t ready to give it up,” Johnson said. “The woolen mill is such a unique, rare business. I love it. I believe in the product, the wool, so much. And we have such great clientele. We’ve done wool for some of these families for more than 100 years, re-carding their wool whenever a quilt cover wears out.”

Grey shares those feelings. “A big part of it for me was the legacy. That, plus the opportunity my parents gave me to be part of a business that is based on helping people through the comfort of wool and the satisfaction of creating family heirlooms through knitting and other fiber-related crafts. I love the product, love the wool. I can talk for a long time on the benefits of wool. I feel fortunate to have been born into a family that knows the value of wool,” she said.

The combination of retiring parents, the tornado’s havoc and the change in ownership put a somewhat new face on the businesses Johnson and Grey run today. “We wanted to scale back a little bit,” Johnson said. As Grey puts it, “we wanted a finer-tuned operation. We wanted to do the things we loved to do, instead of being so diversified.”

When their parents retired, two parts of the business were sold. A wholesale yarn distributorship went to Joel Brinker, a son who had been working in the mill. A knitting machine distributorship and repair business, founded by Brinker in 1968, went to long-time employee Shawn Dolan. He’d been repairing the knitting machines for at least 12 years. Dolan moved that business half a block down the street, but their brother still runs the wholesale yarn business from the mill building. “We buy some of Joel’s yarns for our yarn shop,” Grey said.

The mill strengthened its Nature’s Comfort line of wholesale comforters and mattress pads, a venture started in 1997, and began producing more custom quilts for quilters who sewed their own quilt tops but needed high-quality machine-stitched patterns and binding to finish their projects.

Perhaps the change most noticeable to the public came in the yarn and gift shop. “We were heavily into stitchery and needlework of all kinds on the retail level and we let most of that go. We also got rid of the clothing and the futons we’d been selling,” Grey said.

“We scaled back the retail floor space and just do yarns, fabrics and gifts. That fits our personality and we can do it better. Before, we were too diversified to really devote good attention to detail. We wanted to provide better products and better service, and felt we could do that by narrowing our focus,” she said. “I feel better about our store in terms of what we offer now. We’re more cohesive. Even though the mentality was that we would like to do everything for everybody, we’ve learned you can’t. But you can do a few things and do them really well.”

Johnson agrees. “Two people can’t spread themselves that thin over that much of an area, going to all those different markets.”

Despite the changes, employment remained relatively stable. Counting Johnson and Grey, the mill and yarn shop have eight full- and part-time employees, perhaps two fewer than 10 years ago. Many of the employees work in both the mill and in the yarn shop. “There’s lots of cross-over,” Grey said.

Although mill customers are somewhat different from the hobbyists who flock to the yarn shop, “what they have in common is their love of the fiber,” Johnson said. The mill specializes in processing raw wool from sheep producers, re-carding old wool and fashioning custom quilts for individuals and manufacturing the Nature’s Comfort line, wholesaling it to distributors and independent retailers. Mary Lue’s sells to people having a passion for knitting, crocheting, quilting, weaving and spinning with a variety of natural and man-made fibers. “A lot of these man-made fibers are creating some really fun novelty yarns,” Grey said, although her first love remains wool. “In knitting, there’s always been an interest in wool. It’s never declined that much.”

But trends and cycles influence both the yarn shop and mill. Consider the forces cited by Johnson in a Connect Business Magazine article in January of 1995, nearly 10 years ago:

In the late 1970s, a mood of “self-sufficiency” swept the country and Johnson “tapped into that market and expanded to serve custom hand-spinners, weavers and felters.” People were reading Mother Earth News, growing gardens and raising their own small animals. “The business probably tripled in five to seven years,” Johnson said.

“Then came the big slump in self-sufficiency,” Johnson recalled. Readers of Mother Earth News “decided this was a lot of work.” Women who might have been spinning at home, using wool from their own sheep, put away their wheels and knitting machines and took office or factory jobs. “More women went into the workplace, so they had the money to pay someone else to do it. They didn’t have the time anymore,” Johnson said.

In the mid-1980s, Johnson “seriously considered closing the mill. But we decided we wanted to hang on, so we pursued other avenues.”

Similar forces are at work in 2004. Demand for wool is growing, fueled by a consumer desire to return to natural products. “This desire to use natural products is driven by the food industry, with its emphasis on organic foods. It’s in the clothing industry because people have experienced allergies to the chemicals used both in artificial fibers and in the processing of those fibers,” Johnson said. “More than that, it’s in the comfort. People are discovering the health benefits of wool-filled bedding for pain-related illnesses. And they’re wearing more cotton, silk, linen and wool clothing because these natural materials are more comfortable than polyester.”

Grey said the “nesting” trend that followed the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon also has had “a tremendous effect on knitting and crocheting. We’ve seen tremendous growth and we can’t account for it in any other way than for the events of Sept. 11. It’s a ‘nesting’ instinct. We want to stay home, take care of our families, and appreciate what we have.”

Grey said that in the aftermath of Sept. 11, “people are finding things they can do together, finding hobbies and products they can work on with their children.” And it doesn’t hurt, Grey said, that more movie stars seem to have taken up knitting.

“People are knitting in coffee shops on both coasts. They’re opening knitting stores or yarn shops with coffee shops in them,” she said. But Mary Lue’s doesn’t plan a coffee shop because “we’re determined to keep our specialized focus.”

The yarn shop’s customer base is growing because of the increased interest in knitting and quilting, according to Grey. This growth in customer numbers “comes from the younger generation. The computer generation dropped knitting, but their children are taking it up. Their mothers aren’t knitting, but their children are, teenagers and college-age people.” These children “are going to teach their parents,” Grey predicts.

Although the trend toward natural products has helped wool regain some of its market share, Johnson said “it’s still struggling to recover its reputation.” Manufacturers and big retailers sullied that reputation in the late 1970s, meeting a high demand for wool by selling low-quality fiber at high prices. The January 1999 Connect Business Magazine article quoted their father on that situation:

“You saw the scratchiest things you could imagine,” Brinker said. “Big department stores charged a real high price for low quality wool, and turned off the nation. They shot themselves in the foot—and the whole wool industry in the process.”

Now the wool industry is struggling uphill, trying to erase the impression that wool products shrink, itch and are difficult to care for. “A hundred years ago, wool didn’t itch because always the best and finest was used in clothing. Now they take anything, even if it’s carpet wool, and make it into sweaters.”

The result has a negative effect on buyers. “Women said they wanted to buy a skein of wool for 39 cents. Well, they got it,” Brinker said. Johnson agreed, adding “But once they knit it into a sweater, they couldn’t wear it.”

In 2004, Johnson continues to lament the damage done by the indiscriminate use of poor wool. “It’s too bad there isn’t enough money in the wool industry to really promote consumer education. I could see the same number of wool-filled comforters in a store as down-filled, but there isn’t the promotion money to do it.”

Both Johnson and Grey would like to see the garment industry label the fiber quality of clothing. “All a label has to say now is ‘wool.’ There’s no requirement to list what grade of wool you’re getting. Usually, the only thing that’s indicative of quality today is the price,” Johnson said. “People think if they get a scratching from wool, it’s because they’re allergic to it.” But Johnson said it isn’t an allergy, “it’s only because the fiber is so coarse. We’d really like to see better labeling in clothing.”

Part of the answer to consumer confusion and ignorance is “basic education about the grades of wool and how to care for it,” Grey said. “One of the big drawbacks is they don’t know how to care for it, or had a bad experience. Maybe they’ve seen their mother or grandmother take something this big and shrink it,” she said, holding her arms wide apart and then bringing them together to represent a severely shrunken sweater.

Both Johnson and Grey treat the education of their customers as a continual, obligatory, on-going process or dialogue. It’s almost a conditioned response.

“It’s kind of fun to tell people the truth about what really shrinks wool—it’s the agitation of the fibers! Most people think it’s the hot water,” Grey said.

“You can’t make a sale without educating the customer,” Johnson says with affable finality, as if she’s reciting a law of nature as obvious as the law of gravity.

Spinning A Tourist Yarn

The historic St. Peter Woolen Mill has always been a tourist magnet. Tourists also frequent Mary Lue’s Yarn and Quilt Shop, launched by the mill 40 years ago.

Now tourism is becoming more important to St. Peter itself, according to Pat Johnson and Peggy Grey, co-owners of the mill and yarn shop. The city is “trying to promote tourism because we’ve lost so many manufacturing jobs,” Grey said.

In the last couple of years, two major employers disappeared. With them went more than 500 jobs. Onan, a small generator manufacturer, moved after a corporate merger, while ADC, an electronics assembler, closed many of its plants, including St. Peter.

St. Peter also lost several retailers, “but the people who are left are just fine with being labeled as a town of specialty shops,” Grey said. The mill and yarn shop have always been comfortable with their role as tourist attractions, according to Johnson. “We conduct mill tours for bus groups and we let individuals just walk through and take their own tours.”

Grey said St. Peter capitalizes on several natural attractions. “We have a historic downtown district. There’s Gustavus Adolphus College, with its impressive chapel, and the Traverse des Sioux site.” That’s where a key treaty was signed with Sioux Indians 153 years ago.

The community once staged an annual re-enactment of the treaty encampment at the site along the Minnesota River, but that was discontinued about two years ago. However, the site now includes a new interpretive center, which is open all year.

In his book, Minnesota: A History of the State, historian Theodore Blegen wrote, “few events in the history of Minnesota have attracted more historical interest than the Indian treaties negotiated in 1851.” One was signed at Mendota with the Wahpekute and Mdewakanton Sioux. The other, with the Sisseton and Wahpeton, was signed at Traverse des Sioux, a trading center on the outskirts of present-day St. Peter.

“Traverse des Sioux was movement, excitement, noise, color, smells and display when officials, traders, chiefs and hundreds of tribesman crowded the trading center in the summer of 1851,” Blegen wrote.

The two treaties transferred control of 24 million acres, which meant, “frontier dreams come true” for pioneers, Blegen said. For the Sioux, he said the treaties meant “abandonment of hereditary lands, a bowing to white power, reservations along the Minnesota River, temporary gifts, a trust fund, and cash payments which in large part would be diverted to satisfy debts to the traders.”

Knitting Family Into The Quilt

Will there be a fifth generation?

That question nags Pat Johnson, 54, and Peggy Grey, 46, the sisters who are fourth-generation owners of the St. Peter Woolen Mill and Mary Lue’s Yarn and Quilt Shop.

“We’re having a hard time seeing a fifth generation coming into the business,” admits Johnson.

“I’ve put a lot of thought and energy into it lately because we need to do some long-term mentoring,” Grey said.

Johnson’s two grown children and Grey’s stepson have shown little interest so far. “If these kids are going to learn the business, they need to be here now,” Johnson mused.

Their best hope at the moment is a niece, the daughter of their sister, Donna Seitzer-Ter Beest. Donna died of cancer in 1990. The niece lives in California, pursuing a career in theatrical costume design. “She says she’ll be back in no more than three years,” Grey said.

Until her death, Donna had been immersed in the family business. “I don’t remember her doing anything else,” Johnson said. Donna earned an associate’s degree in commercial art at South Central Technical Institute in North Mankato in the early 1970s. “She was our public relations person and graphic artist. She was our resident knitting machine expert, wrote knitting books and created knitting patterns,” Johnson said.

Spinning Out Of Control

Twisters imprint lasting memories that seem always fresh.

Sisters Pat Johnson and Peggy Grey effortlessly recall the awesome power of a killer tornado that struck St. Peter March 29, 1998, nearly wiping out the town and the businesses that they own.

The experience left Johnson temporarily unable to speak after she and her husband, Bob, emerged from their home, which escaped major damage, and tried to reach the St. Peter Woolen Mill. They cautiously picked their way around collapsed power lines and uprooted trees, overturned cars and debris from shattered buildings that lay scattered along their route to the mill. They saw twisted canoes, swept by the wind from St. Peter’s Alumacraft plant and wedged in the upper branches of trees still standing.

“My heart was beating as I held onto Bob’s hand, walking the last six blocks. I couldn’t speak. All I could do was take short, quick breaths when I saw yarn hanging from what was left of some trees,” Johnson said.

Grey was on her way home from a Milwaukee yarn show when the storm struck about 5 p.m. She and her parents reached St. Peter about eight hours later, finding the powerless town dark and silent. “It was pitch black and totally quiet. The only things we could see were in our headlights.”

When they reached the mill and Mary Lue’s yarn shop, Grey said “we focused our headlights on the building. We were seeing mounds of stuff, but couldn’t tell what it was. We picked some up in the dark and realized it was yarn. That’s when a sinking feeling hit.”

During the cleanup, Grey and Johnson learned something about a tornado’s invasive power. About $100,000 worth of yarn, wound in bulk on cones, had been stored on the mill’s second floor. It had been bagged in plastic and packed in sealed cardboard cartons.

“We thought we could salvage and repackage it because the boxes hadn’t been opened,” Johnson said. But when they removed the yarn from the sealed boxes and protective plastic wrapping, they found the yarn “was full of debris, mostly insulation from our building, shreds of it. The wind had so much force that it shredded the insulation and drove it through the cardboard and plastic and into the yarn.”

© 2004 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Hey there Pat,

I still have your sewing machine I got from you when I was 22. Just got it tuned up again. Thank you for such a splendid durable piece of equipment. I think you everyday when I go into my studio. I am seeking

cashmere yarn for knitting and crochet, Do you all sell it? And do you have a product catalogue?

My address is 578 South K Street, Livermore, Ca 94550. phone 925-487-7620. Hope to see you this year one way or another. Best wishes that’ll are well and happy.

Love

Nancy