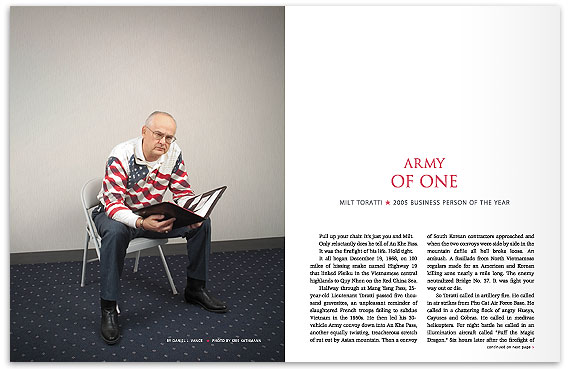

Milt Toratti — 2005 Business Person of the Year

Photo by Kris Kathmann

Pull up your chair. It’s just you and Milt.

Only reluctantly does he tell of An Khe Pass.

It was the firefight of his life. Hold tight.

It all began December 19, 1968, on 100 miles of hissing snake named Highway 19 that linked Pleiku in the Vietnamese central highlands to Quy Nhon on the Red China Sea.

Halfway through at Mang Yang Pass, 25-year-old Lieutenant Toratti passed five thousand gravesites, an unpleasant reminder of slaughtered French troops failing to subdue Vietnam in the 1950s. He then led his 30-vehicle Army convoy down into An Khe Pass, another equally twisting, treacherous stretch of rut cut by Asian mountain. Then a convoy of South Korean contractors approached and when the two convoys were side by side in the mountain defile all hell broke loose. An ambush. A fusillade from North Vietnamese regulars made for an American and Korean killing zone nearly a mile long. The enemy neutralized Bridge No. 37. It was fight your way out or die.

So Toratti called in artillery fire. He called in air strikes from Phu Cat Air Force Base. He called in a chattering flock of angry Hueys, Cayuses and Cobras. He called in medivac helicopters. For night battle he called in an illumination aircraft called “Puff the Magic Dragon.” Six hours later after the firefight of his life, he and his men somehow, someway, extricated themselves from An Khe Pass, many dead, and next morning Toratti was on Highway 19—again.

Be advised he is sharing this story with you only after being dogged by the writer. Toratti is no braggart. He says he was only doing his duty. But the writer felt he had no other story to write save this one, because it frames Toratti for you better than any thousand words of puffery.

Today when searching his eyes, you see a human being that took the worst of flak and made it through alive. A business owner or entrepreneur can draw strength from someone like that.

That said, Milt Toratti is the “master facilitator” of Riverbend Center for Enterprise Facilitation (RCEF), the economic development arm of Blue Earth County. It’s a one-employee nonprofit operating on a skinny $50,000 budget in a cramped Mankato office. RCEF and Milt have helped about a thousand existing and potential entrepreneurs discover and express their passions through their business.

Is RCEF good at what it does? In 2003, the National Association of Counties named it the nation’s “Best Rural Economic and Community Development Program.” Now Milt has earned Connect Business Magazine’s “2005 Business Person of the Year” award by being the top choice of our panel of judges.

Tell me of your relationship with Bill Popp, owner of Popp Telecomm and limited partner in the Minnesota Timberwolves?

I was in Forest Lake working for a venture capital group and had just finished helping a few companies secure private placement memorandums. I then went to work for Bill Popp after first having an interview with the Secret Service. It was a high security situation because of his business. I was security manager of his property and on his personal staff. Essentially, my wife Jan took care of the inside and I had the outside. On occasion I’d work with his staff at corporate headquarters privately helping with problem solving.

What were your impressions of him?

The greatest lesson he taught me was attention to detail as an entrepreneur. He had three jobs in his entire life: paperboy, lineman, and owner of his company. He founded Popp Telecom in the early ‘80s after the break-up of the telecommunications industry. His company was one of the first in Minnesota to sell long distance service. His offices are all over America now.

Can you give examples of his attention to detail?

He was like Vince Lombardi. If you weren’t at “team meetings” 15 minutes early you were late. And with him you did your research before the meeting so you were thoroughly prepared. The other attribute I learned from him was “punish in private, praise in public.” He had to let several managers go, but he always did it privately so there wasn’t any embarrassment, thus preserving their dignity.

Tell me about Harlan Jacobs, the founder and president of Genesis Business Centers, the well-known for-profit, high-tech incubator. He’s an acquaintance of yours.

He is an opportunist entrepreneur. Several years ago he spotted the potential market for the defibrillator and got in on the ground floor. Now that product is around the world. He is a risk taker, but not really one. Let me explain: As an entrepreneur, he understands risk and how to mitigate it. No matter how risky the investments he makes may appear, know that he has reduced that risk by having solid research to back it up. So he risks capital for a bigger gain on the far end and makes long-term investments. He is extremely good at risk assessment and understanding an entrepreneur’s dedication.

How did you meet him?

About 1990 in northern Minnesota when I worked for Minnesota Technology as a business technology specialist. I was the only one doing that with Minnesota Technology. Essentially, what I’m doing at RCEF is what I did then. I was looking for innovative people in technologies. We ran across each other at conferences where people were promoting products and seeking venture capital. We got to know each other through assessing venture potential and struck it off well.

You have invited Jacobs to southern Minnesota to visit promising entrepreneurs. Do you think people here realize how big of a deal it is to have someone of his stature drive here to contemplate investing in a start-up?

No. But we want his visits to be low-key. Venture capitalists that want you to know how important they are miss out on the venture anyway. Harlan’s visits are low-key and he wants them to stay that way. He’s been here three times seeing RCEF clients and hopefully will make more trips.

When someone walks off the street and asks if you’re qualified to help them with their business, what do you say?

First, I don’t look at myself as “qualified.” I look at myself as having a passion for what I do. Anyone can do my job if they have the passion to help local people. To me facilitating isn’t a job; it’s a lifestyle. It’s what I’m supposed to be doing. To me, this job is really all about service.

That said, if a client wants to know more about my qualifications, I tell them my work with small groups and individuals started as a schoolteacher in Duluth. It carried over in the Army when I was the Director of Instruction for the 1st Army Leadership School and learned facilitative and negotiations skills. After returning from Vietnam in 1970 I went to the Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute and became a race relations officer/negotiator calming angry crowds in riot control situations and conducting race relations training at various military installations. I was also tapped to assess levels of racial tension and develop human relations programs for various commands. Then I was trained as an organizational effectiveness officer and sent to Munich, Germany, to serve as instructor and later as Chief, Human Relations for Europe and 7th Army. In that capacity my colleagues and myself received the award as the best trainer of trainers in the United States Army by the Army Research Institute. So, essentially I have been a facilitator since 1970 in various capacities. In 1997 I attended Sirolli Institute training for enterprise facilitators before assuming duties in Blue Earth County.

As for other qualifications, I grew up on the Iron Range and watched the mineworkers. I worked in the mines for a while as a drilling and blasting foreman and saw how unions affected workers. Those workers used to be innovative and creative, but in time they became lazy. They lost their self-initiative and creativity by working 8 to 5. Before the mines came they would fix their own tractors and cars. Then all of a sudden they had service stations. At work if they tried to exhibit any self-initiative, the union would stop them even when they were increasing productivity. The sense in the mines was that if you were doing something good that wasn’t in your job description, stop doing it.

Then I graduated from Univ. of Minnesota-Duluth and became a social studies and speech teacher in three different school systems at the same time. I did it that way because I didn’t want any one principal or superintendent having their hooks in me. So in the morning I might be at West Junior High and the afternoon at Central or Morgan Park. In all these schools there were good teachers, but once again the union would get their claws in you and you could do only so much. You couldn’t be just a good teacher with a passion. You had to belong to the union first and that was primary. I learned that my first day. I was supposed to go to school and teach my class and that was it. Those extra things I wanted to do such as counseling students or come in two hours before class and leave three hours after—that was out the window. It became an 8 to 5 job just like the mines. The union controlled your job description and what you would do and how you did it. If you did more than that, they would go complain about extra pay. And I didn’t want that. I thought I could do “service” as a teacher and found out quickly I couldn’t. This was in 1965 and early 1966.

So this was before you went into the Army?

Yes. I’m a “service” type of guy. I wasn’t allowed to excel in serving others at the mines or at teaching. So I went into the Army to test my leadership abilities and retired 23 years later. The facilitating I do now at RCEF is an offshoot of what I am as a person. I’m really a servant. And wherever I go in life, my mission is to work myself out of a job. When I do that I know I’ve done well.

What do you mean by “working yourself out of a job”?

I had clients in this morning before this interview with you. I’m retiring from RCEF in April of 2005. My goal here is to work myself out of a job, i.e., to make my clients independent and self-sufficient, so they don’t have to rely on me or anyone else the next five years.

Sounds like the old axiom of teaching a person to fish rather than giving them fish to eat.

Yes, that’s my purpose. In April I will have been here eight years. By then I will have had more than a thousand clients, plus another thousand on the Internet. That may sound like a lot, but at any one moment in time I have only one client. When that person listens and understands our model and becomes self-sufficient, then I’m out of a job with them. They don’t need me anymore. So then the next client comes in, and the next one. Each are treated the same way; one at a time. I work hard to get myself out of a job so they can succeed as entrepreneurs and contributing community members.

In 2003 RCEF was named the best rural economic and community development program in the nation by the Association of Counties. Really, what makes RCEF so much different from what everyone else is doing?

To succeed you must have the courage to be first, best and different. RCEF was first in the way it operates. We’re best because the Association of Counties bestowed that award. You can be best only if someone else says it; otherwise you’ve lost your humility. We are different because we are a staff of one and have a great board of directors. To do what we’ve done here, a “normal” government program like ours would have a staff of ten. We are efficient. Our cost per job created is $987. The return on investment to Blue Earth County is something like 47 times a year. How do you handle a thousand clients with a staff of one and continually take on more and more? It’s called efficiency and having fun. Blue Earth County has been generous in funding us with $50,000 annually and we respond with cost savings to clients, jobs created, jobs saved, and with efficiencies in small businesses. That’s why we won the award.

Compare your model of economic development with the status quo?

Traditional economic development works like a funnel. It recruits as many people as possible to get in the funnel at one time. Through a series of training programs, conferences and workshops, they attract up to 500 companies or people, let’s say; and at the end of the year squeeze out at the bottom of the funnel up to three winners. This means the others are losers. So traditional economic developers, using their own bureaucratic criteria, pick winners and losers.

The RCEF model is just the opposite, a pyramid, which is really an inverted funnel. Our base continues to grow rather than diminish. Every client coming in is a winner. No one loses. Even persons choosing then not to start a business win because of the money they saved from not following through on an unwise choice. But that same person might remember the principles they learned from us and come back for help five years later. Last year a student of mine from 1981 at Indiana University contacted me after 23 years. He found me in Colorado on vacation. He said he’d finally “got it.” Two days later I was helping him with his marketing company in New York City. We all develop at our own pace. That former student of mine wasn’t a loser in 1981; he was a winner. I just had to sit and wait for him, in his own timing, for him to bring his passion, his own business idea to fruition.

I already know what will happen when I leave Mankato. Beforehand I’m going to transition as many clients as I can to my replacement. However, RCEF is all about relationship building, not about business building. Building relationships is a process, not an event. Creating a business in a traditional model is an event. There is a big difference. Some of those clients I first met in 1997 in Blue Earth County will find me in Ohio. They will come by the house and we will have a cup of coffee. Maybe they will talk about business. Maybe it will be something personal, but all business is based on relationship and the human element. People don’t care how much I know, until they know how much I care.

Further explain traditional economic development in your terms.

Traditional economic development is all about the “principle of contribution.” They say that to have a successful business you must demonstrate that you can make money, create wealth, service customers, produce more, measure your achievement in cash and defeat your competition at all costs. That’s the principle of contribution.

Our model is one of entrepreneurship. We believe the purpose of an entrepreneur is to use his or her business to express a personal passion. That’s it. However, if you express your passion through your business, you will love what you do, do what you love, you will make money, you will create wealth, and you will serve your customers well. You will measure your performance in cash and you will beat the hell out of your competition. With that attitude, how can you fail?

So in your eyes internal motivation is everything.

The worst thing I can do is to convince you to go into business. If I have to convince you, you’ll fail. That’s why the RCEF client failure rate is less than one percent. With traditional government programs it’s between 82-90 percent. The RCEF rate is lower because it’s based on passion, and if you are running your business on passion, you won’t give up. It’s called sisu, which is a Finnish word for persistence. It’s not who you are that holds you back; it’s what you think you’re not.

Tell me more about your clients.

First, there are the un-retirees, who think retirement isn’t for them. An example is our first client in 1997, Arnie Lillo. Since then his son has joined him in his business and within five years his grandson will too. Three generations will be working together. Arnie is a metals fabricator who started Timeless Images in Metal. He has a niche market in making antique tractor parts and ships them around the U.S.

We also have a few social entrepreneurs. Did you know an entrepreneur doesn’t have to own a profit-making business? An example is One Bright Star, which provides services, counseling and financial assistance to families experiencing loss of a sibling or child.

I’ve also done speeches for cities on economic development and I’ve met with 3M executives. So it runs the gamut, from people with ideas, inventors, families or existing businesses. People often want to hear our biggest success stories, but I like to say there really isn’t one. It’s all relative to who you are anyway. Imagine you’re a single-parent mom recently divorced and laid off, and no one will hire you. You’ve now decided you’re going to do what you’ve always wanted to do to make a living. Then I will help that person. To me, helping that person is much more of a success story than helping a Fortune 500 executive succeed.

I do get large-company executives and owners coming in. They are the ones that wouldn’t go to a traditional economic development person. Here there is confidentiality. They often say they’ve hit the wall and need assistance jumpstarting the company.

Here is what I tell them: Go to work and do nothing for a whole week. They look at me like I’m insane. I tell them to put away their cell phone, Palm Pilots and notebooks. I tell them to clear their schedules and do nothing for a whole week—and then call me once a day. The first day they go nuts and drink all the coffee. I tell them to keep doing nothing. Pretty soon they get tired of the coffee and get out of their office. They go for a walk on the production floor and talk to employees on break. By the end of the week they’ve called back to say they understand. They have learned the most valuable lesson of all, something I call the six “A’s.” You have to be available, accessible, and approachable to anyone and about anything at anytime.

An executive can go to work and be available all day. They can be accessible because they are in the building. But if not approachable, they have lost touch with their company. They learn this lesson by “doing nothing.”

It’s like a kid coming home at the end of the day after having a problem at school. If the parent is available, accessible, but not approachable, that kid will find something or someone else to satisfy their needs. Be approachable and you will always know what’s going on. You will be able to make the changes necessary for your business to continue growing. Success means developing new habits because people really do not determine their future. People determine their habits and their habits determine their future.

You have helped larger companies in this region. Does it sometimes get to you that they make these important business decisions, and you’ve helped these companies, and yet because of confidentiality you get none of the credit, i.e., no one knows you’ve helped?

Seeking credit isn’t in our model. In fact, doing this interview isn’t either. Really, the attention is embarrassing. It’s outside of what we do. We don’t advertise for a reason. All our clients come on referrals. We’d rather sit in the background. We’ve helped maybe a dozen larger projects and want to retain anonymity by walking away from the attention.

Why do some people seem to intensely dislike you?

The reason why [some people] dislike me is because I will not compromise my beliefs. I am a compassionate conservative who works hard to help others achieve self-sufficiency and become independent thinkers. I also believe the most important characteristic of a leader is to be predictable. For example: employees, colleagues, or staff making correct decisions when the owner or manager is absent demonstrates that the organization’s values have been embedded by a predictable leader. I am also a person who does not believe in political correctness. So if others resent me for being principled with a strong belief system and being politically incorrect, then so be it.

RCEF goes beyond Blue Earth County, doesn’t it? Isn’t it more a regional economic development group?

Blue Earth County has 14 communities and I have clients in 90 communities. Some fly in from out of state to Minneapolis and drive down on Friday afternoons to spend an afternoon or maybe Saturday morning. We’ll discuss their needs from marketing, to commercialization of products, to proprietary protection, leadership, strategies, management, whatever. Some clients drive in from other parts of Minnesota, Wisconsin and the Dakotas. We don’t have a watch or time clock. This is a 24/7 operation, unlike that of the mines in northern Minnesota or schools in Duluth. If someone wants to talk, our doors are open because we are available, accessible, and approachable.

What about the MSU Entrepreneur’s Fair you helped start?

I’m not going to do it again. Dr. Flannery of MSU went on sabbatical and I’m retiring, so we aren’t doing anything this year. But in 2002-03 it created excitement. I’ve been getting calls all fall asking about the next one. People are expecting it to continue. It may pick up next year with the right leadership because there is no lack of entrepreneurs interested.

Really, it was a celebration of entrepreneurs with entrepreneurs. The worst anyone can do is to only listen to me. They need to learn how to network and make friendly relationships with their competitors. I call it “co-opetition” instead of competition. The entrepreneur fair had inventors, small businesses, entrepreneurs, and students presenting. We had community support from banks and service organizations. It had the entrepreneurial spirit; keeping it alive and well in the region is important work.

Some folks say that when you retire in April, RCEF retires. You are RCEF.

That’s humbling to hear, but wrong. We have a tremendous board of directors. They aren’t trying to replace me. But they are redefining and tweaking the program, and looking for a person that fits. I believe that person with passion will step forward. The model works. If I have to do the training from Ohio I will. I will do whatever I can to help that person launch successfully to further local entrepreneurism.

Feedback you receive from clients?

One interesting dynamic recently since I announced my retirement: Clients from several years ago are coming back. I’m also getting feedback from clients that have taken our model and helped their business friends and neighbors. Rather than call me, they’ve demonstrated the model to others. That’s exactly what I mean about working myself out of a job. So even if the position to replace me isn’t filled, the model is already out there and being taught by our former clients. Past clients have even set up their own mentor groups.

What will you do in retirement?

The move to Cincinnati will be my thirtieth. Mankato is the longest Jan and I have stayed anywhere. It’s a great area. But we are moving to be near our grandkids. I’ll write books and do motivational speeches there.

Beginning at age 11 when I filled my first dump truck using a hand shovel and all the way through to today, I’ve never missed a day of work. My dad was a miner and entrepreneur. We had up to 13 different trucks in our yard at one time, everything from a garbage truck to a ‘24 Buick touring car we used as a taxi. We had welding and machine shops. It was work, work, work, and more work. Those same work habits have stayed with me. So I’ll continue working in Ohio, but at a different pace and with different people.

How Milt Toratti (And Our Two Runners-up) Won Our Award

In September, Connect Business Magazine ran a full-page ad with detailed nominating instructions for our “2005 Business Person of the Year.” Five of our eight judges were the chamber of commerce presidents from Waseca, Fairmont, New Ulm, St. Peter and Greater Mankato; the remaining three were Connect Business Magazine staff members. Each judge had up to three votes, with first place counting five points, second place three, and third place one. Mr. Toratti earned four of eight first-place votes, garnering solid support throughout the region.

One-stop shop

RCEF is a one-stop shop, everything and anything, from people and resources to financing, business plans, organizational effectiveness, personal problems, and career development. We don’t have a niche. Traditional programs often target certain industries, but we work the breadth and depth of all businesses in all sectors of the economy. If you walk in the door, there is time for you.

However, I don’t like working with franchises based outside Minnesota that are opening in this area. I made a mistake working with one and that’s a business that failed. They wanted specific help in getting a local franchise off the ground. I will, however, work with a local franchise owner. —Milt Toratti

Master Educator Too

Milt Toratti, master facilitator of Riverbend Center for Enterprise Facilitation, enjoys teaching and being a bookworm. He has been a professor at Indiana Univ. and Univ. of Toledo and a business development specialist at Univ. of Minnesota-Duluth. He has an MBA from Webster Univ. He has written two books: Adapt to Change: Manage Growth and The Courage to Be First, Be Best, Be Different, the latter featuring profiles of 16 Blue Earth County entrepreneurs.

FACT:

Gov. Arne Carlson appointed Milt Toratti to the Minnesota Board of Invention District 8. In 2003, Gov. Tim Pawlenty re-appointed him as “at-large.” Toratti is also a SCORE Chapter 328 counselor.

Getting On Board

Riverbend Center for Enterprise Facilitation Board of Directors, as of January 1, 2005:

Kathleen Trauger, Minnesota State Univ.

Dr. Yvonne Karsten, Voyageur Web

Dan Deschaine, Rasmussen College

Jerry Rollings, Lake Crystal Economic Development

Andrew Johnson, Johnson Law Office

Pete Steiner, KTOE Radio

Scott Weilage, Weilage Corp.

Kent Thiesse, MinnStar Bank

Richard Tofte, Wells Fargo Bank

Julie Storm, Alterra

Al Bennett, I&S Engineers & Architects

Chad Surprenant, I&S Engineers & Architects

Kip Bruender, Blue Earth County

Chuck Juntunen

© 2005 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.