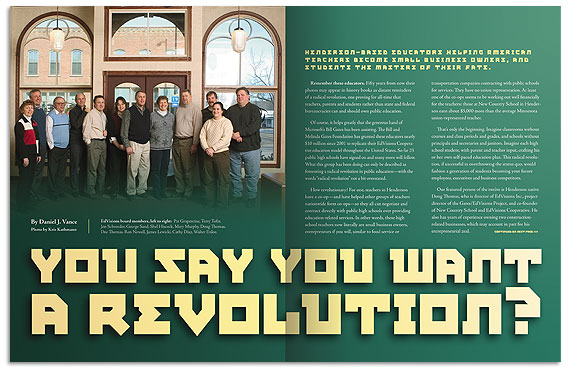

Doug Thomas

Henderson-based educators helping American teachers become small business owners, and students the masters of their fate.

Photo by Kris Kathmann

Remember these educators. Fifty years from now their photos may appear in history books as distant reminders of a radical revolution, one proving for all-time that teachers, parents and students rather than state and federal bureaucracies can and should own public education.

Of course, it helps greatly that the generous hand of Microsoft’s Bill Gates has been assisting. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has granted these educators nearly $10 million since 2001 to replicate their EdVisions Cooperative education model throughout the United States. So far 23 public high schools have signed on and many more will follow. What this group has been doing can only be described as fomenting a radical revolution in public education—with the words “radical revolution” not a bit overstated.

How revolutionary? For one, teachers in Henderson have a co-op—and have helped other groups of teachers nationwide form co-ops—so they all can negotiate and contract directly with public high schools over providing education-related services. In other words, these high school teachers now literally are small business owners, entrepreneurs if you will, similar to food service or transportation companies contracting with public schools for services. They have no union representation. At least one of the co-ops seems to be working out well financially for the teachers: those at New Country School in Henderson earn about $5,000 more than the average Minnesota union-represented teacher.

That’s only the beginning. Imagine classrooms without courses and class periods and grades, and schools without principals and secretaries and janitors. Imagine each high school student, with parent and teacher input, crafting his or her own self-paced education plan. This radical revolution, if successful in overthrowing the status quo, would fashion a generation of students becoming your future employees, executives and business competitors.

Our featured person of the twelve is Henderson native Doug Thomas, who is director of EdVisions Inc., project director of the Gates/EdVisions Project, and co-founder of New Country School and EdVisions Cooperative. He also has years of experience owning two construction-related businesses, which may account in part for his entrepreneurial zeal.

Have you met Bill Gates?

No, and I likely won’t get the chance. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has an annual meeting with its “replication grantees,” of which we are one. Bill Gates Sr. runs the Foundation. My wife Dee and I however have been to the Foundation, which is housed in a nondescript building on a Seattle lakefront. There aren’t any signs announcing its presence because they don’t want to draw unwanted attention. However, the parking lot and front door does have guards.

So at one time you applied to them for a grant?

They initiated the contact. In our case, they came here one day in early 2000 and stayed at the school two hours. Tom Vander Ark of the Gates Foundation and Tony Wagner of Harvard, the Foundation’s consultant, talked to teachers and kids. Then we all walked up the street to a restaurant in Henderson for lunch. Harold Larson, the superintendent of Le Sueur-Henderson Schools joined us, and he told them of the district’s role involving the “radical change” brought about by our New Country School.

While we were walking back to the school, Tom Vander Ark told me that they were “going to give [us] some money.” When he asked what we would do with it, I said, “We will try to replicate our model in other schools.” He said, “Just tell us how much you want and what you will do with it.”

That afternoon I asked the teachers of New Country School (in Henderson) what we should do with the money. They all wanted to keep it in Henderson. To accomplish that, we first had to form a new nonprofit, which became EdVisions Incorporated. I then wrote a two-page proposal to the Gates Foundation. We thought of it as economic development. When the first grant arrived in January 2001, more than $4.3 million in business came to Henderson.

You’ve experienced rapid growth. In four short years your “co-op” model has been replicated in how many high schools?

Twenty-two—and the Gates Foundation wants us to create an additional thirteen using our model, bringing the total to 35.

How did the Foundation learn about New Country School?

Ted Kolderie is with a St. Paul nonprofit, the Center for Policy Studies. For a number of years he’d been interested in our teacher/owner concept and learning program. He was one of the people in 1993 that pitched the Le Sueur-Henderson school board for New Country School.

Vander Ark (of the Gates Foundation) told us that some people carry baby pictures around with them. He said that Kolderie had “baby” pictures of New Country School. Kolderie had gone to the Gates Foundation on our behalf after hearing the Foundation was interested in high school reform. He placed the pictures on Vander Ark’s desk and told him he had to see our school.

Up until yours, how many other organizations had received Gates grants?

We were only the third organization in the nation to receive a high school replication grant. The Foundation has made about 250 grants total. Some are for breaking down large, traditional high schools into smaller learning communities. Others are for at-risk schools.

So what you are accomplishing here in Henderson is similar to what a restaurant owner does with a good restaurant concept. You are franchising it out?

We don’t call it franchising. For the most part the U.S. has two different types of organizations involved in educational reform. The first is involved in professional development, i.e., trying to convince schools to change. The second is involved in managing schools. These are called EMOs (educational management organizations), such as Edison Schools, Aspire Schools, Sylvan Learning Centers, etc.

When forming EdVisions Co-op Inc., our internal question was whether we wanted to be a professional development organization or an educational management organization. We decided we wanted to be a professional development organization, but on the frontline, developing new schools and programs. We didn’t want to on-site manage schools and programs because we wanted teachers to “own” their school’s instructional model.

So we became what we call an “EDO,” an educational development organization, rather than an EMO or CMO, a charter management organization. We help people start the charter process, sub-grant to them from the Gates Foundation, and stay with them at least three years until they can get the ball rolling themselves.

How much has the Gates Foundation granted you, total?

The first grant was $4.3 million; the second $4.5 million. As for the current size of our business, when you include the services (such as payroll and medical benefits) we offer to member schools, EdVisions Co-op in just four years has become a $10 million a year business. It’s been amazing. The payroll benefit service we offer our affiliated schools alone is around $5 million annually. I suppose you could also describe us as a service co-op for new, innovative, and in most cases, charter schools.

So when a school becomes affiliated with you, do they become part of the co-op too?

Some do. But our idea is to get them to create their own. At first we thought that was fine; so we have ten schools in our co-op. But to most of them now we say no because we want them to create their own, to do what we did. The whole idea is to empower teachers to help them own their own professional services and to have them act more like a law firm or a medical practice. We are convinced that teachers will never be treated like professionals until they organize like them.

Are there legal restrictions in other states on forming co-ops like yours?

Some states are “closed shop.” That means unions there have great power and almost no one can work in a public school independently of them. Unfortunately, in some states, that defines the whole labor arrangement. In other states, school boards have the ability to contract for services but restrictions exist when contracting with teachers. As soon as they consider contracting with a teacher, a law kicks in to force them to contract only with the union. We probably won’t fully expand into all these states. Presently, we can expand there only with our high school reform instructional model; we can’t get the teacher/owner model in.

Why do teacher unions oppose your model?

I have no idea. Unions have been trying to control their profession all these years. And that’s exactly what we offer teachers—the ability to do that. It just baffles me that unions would not see the value in having teachers as owners. When I served on the school board in Henderson, and then later with Le Sueur-Henderson (four terms total), every time contract negotiations with the union came up, my question to the board was, Why don’t we tell them they can have all the money?

This is exactly what we do in our schools. The teachers control the money through their co-op by negotiating a blanket contract with the school and the parents get the results. If the results aren’t there, the parents and kids can go elsewhere. To me, our way makes basic business sense. Until we apply this kind of flexibility, we’re going to continue having a quagmire (with teacher contract negotiations) year after year after year.

It would appear as if unions would lose members and dues income if your model becomes widespread.

I once had a meeting with some national union representatives. I asked them, “Why not offer associate memberships?” I was referring to teachers such as ours, ones currently not affiliated with the union who might want all the professional services associated with union membership except for negotiation services. But they won’t offer associate memberships.

Switching gears: What events in your life helped you and others start this cooperative?

Other than growing up really poor? Our family, without question, was one of Henderson’s poorer families—I grew up in a close-knit neighborhood just west of town. It may be a cliché, but in being so poor we learned how to make our own fun and be more creative. Everything we owned was “self-made.” There was an egalitarian thinking about all we did. We had lots of neighborhood picnics and other social events.

Our co-op model fits that sort of mindset. For instance, during this interview there are about twelve people from EdVisions Co-op talking and working together in an adjoining room. This monthly meeting, which I’ll soon rejoin, is the highlight of my month. I really enjoy being with twelve intelligent people to make plans for our future. That’s heaven for me.

As for other motivators: When I went off to college to become a teacher, I had this idyllic, small-pond education background. Our senior class in Henderson had only 19 students. Out of necessity we were all involved in sports, music, and theater—literally everything. And through those extracurricular activities, we learned leadership skills.

Then after earning a degree and beginning as a teacher at my first high school assignment, I was stunned at the number of kids left out of those activities. The poor kids were left out; so were the really smart kids. Only about 20 percent of the kids were active in school activities. Another thing shocking me was the level of concern for students shown by a number of teachers. Those concerned about kids were completely kept out of doing anything to better the system. The system was set up this way and you couldn’t do much about it.

The children in that school weren’t learning leadership skills, which to me is the most important thing they could learn. Students need to learn how to organize, research, make decisions, and work alongside others. They need to practice those skills in school. Most people don’t function well in our democracy because they never had the opportunity to practice democracy in school. So they don’t know how to do it. Schools are oligarchies, run by a small group of people. To me, this is also why teachers sometimes have trouble fitting into our teacher/owner model. They’ve never been put in charge.

I thought the situation might be better at a larger school, but it was worse. I was appalled at the lack of professionalism. So I walked away from teaching. I loved the kids, the activities, the teaching; but the established management and teaching systems made no sense.

So what did you do?

I left teaching in 1980. Along with a partner, I formed construction and historical preservation development companies. At its peak we had 20 employees. The businesses went well, but I still had the desire to be in education. So in 1987, I took on a part-time teaching job in Waconia, just to see if the system had changed. I taught in the morning and returned to my businesses in the afternoon. By mid-year I couldn’t continue. The situation was worse there than in the other two systems I’d taught.

That same year I began taking classes at the Humphrey Institute (Univ. of Minnesota) and also was elected to the local school board. In my “Public Service Redesign” course class, the professors were asking these questions: Why does the public school own all its own services? Why are they running their own buses? Why aren’t they contracting out food service? Why aren’t they contracting out their educational services?

In 1990, we sold the construction side of our business, but kept the historical preservation part. The day after we sold, Joe Nathan of the Humphrey Institute called and asked me to come work for him. He wanted someone with educational, main street and school board experience. There weren’t too many people around with that resume. So I became the southern Minnesota coordinator for the Center for School Change. We had Blandin Foundation money to create innovative programs in rural Minnesota. In the next five years I visited nearly every school building in the southern half of the state except for the metro area, from St. Cloud on south.

This is how I became exposed to the school reform business. In the early ‘90s, we began creating New Country School in Henderson. I was carrying around inside me then all those ideas from the University of Minnesota and now the new charter school law allowed those ideas to become reality. I took all this to the Le Sueur-Henderson school board. I told them a charter school would eliminate the collective bargaining issue, help us get serious about accountability, and simultaneously we could create a new business model, the co-op. Those were radical ideas.

The board denied the first request. In 1993, they changed their minds. I really commend that board. In early 1994, they approved a contract with New Country School and the EdVisions Cooperative was created to staff the school.

How do teachers become teacher/owners? Do they have to pay in?

There are no dues. As a co-op, the teachers contract with a school board for educational services. Here’s an example of how it works: let’s say the co-op contracts with the school board to provide educational services for $500,000. If the co-op performs those services for $496,000, then it would have a surplus of $4,000 at year’s end. By law, the co-op must then distribute that money to its members. Teachers can become members of the co-op after first being recommended by the school board to teach.

Can teachers in your model earn more, for instance, by also being a janitor, cook or groundskeeper?

Absolutely. That’s the model at New Country School. The teachers also divvy up administrative responsibilities. Our teachers in Henderson earn about $5,000 above the state average—and that’s before they begin doing their extra job duties. Our teachers also can earn extra by helping out with secretarial, technological, and financial services. This is the whole idea of becoming a co-op, to help teachers become owners/entrepreneurs. Several teachers at New Country School make more than $50,000 plus benefits by providing other services to the school.

On to another area: Are traditional, geographical school districts obsolete?

Yes. The only reason you need them around is for their taxing authority because the state still has, primarily, a property tax system to fund public schools. Charter schools have no taxing authority at all. The state is the sole supplier of funds for schools. So we’re talking about a parallel system that is being created in this state. You have a state chartering system and you have a local district system. They are both public systems, but running parallel, funded in different ways, and created under different authorities.

What’s stopping four people that think exactly like you from winning a school board election, abolishing the old district system, and making all the schools in that district into charter schools like yours?

Nothing. What you mentioned is the “all charter district” idea. But Minnesota law says that to remain a school district the district must maintain control over at least three grades of only one school. So let’s say Madelia wanted to become an “all charter district.” The school board there still would have to maintain control over three grades in one of their schools in order to remain as a public school district in Minnesota.

Waseca just started an in-district charter school. If desiring, they could charter all their schools except for three grades in one school. It’s one way to reorganize districts, get more site management, and get off the property tax merry-go-round.

The current system is obsolete and for those districts faced with consolidation, we have to figure out a new way to fund schools. I’ve counseled with dozens of school districts about consolidation and told them not to relinquish their taxing authority. Do whatever you must, but don’t give up your taxing authority, because then your community will be subject to the whims of the largest community in the district. Then that city can vote in all kinds of tax hikes and you will never have the power to stop them. By keeping your taxing authority, if things don’t go particularly well in consolidation for your side of the district, you can simply re-open your schools.

The traditional geographical school district is becoming obsolete also because of open enrollment, post-secondary options, and alternative schools. As more choices keep coming, the old traditional school district becomes even more obsolete. And the choices won’t stop coming.

But this is so “out of the box” for most people.

Take this a step further into the schools. You asked, Why have school districts. I ask, Why have courses? Who determined that curriculum should be boxed the way it is and have it be the only way to deliver education? By asking these questions you cut to the heart of the state bureaucracy. They box it up this way because they can keep track of it better. The current education system is based on bureaucracy. It doesn’t make much sense though for the kids.

We’ve talked about the co-op model. But how is your model of instruction different from the traditional system?

Just the word itself: instruction. We don’t have that. We have self-directed—and largely self-paced—learning. It is self-paced, yet students still must meet state standards by certain deadlines in order to graduate. How our students meet them is yet another question. They meet the requirements by following their own interests while being guided by a teacher. In traditional instruction, the teacher tells students what they should know. It’s a top-down approach. That approach results primarily in one kind of learning, memorization, and it facilitates traditional testing. It does not facilitate deep learning, which is when kids take ownership in and actually become interested in their schoolwork.

The difference between creating schools now and in the ‘70s is that as a profession we know a lot more now about learning, assessment, and evaluation. And now we have the policy and organizational vehicles, the charter school idea, to take this new knowledge about learning and make it happen.

What do you say to critics who say your students sometimes don’t test as well?

First off, what do tests measure? All you’re doing on tests for the most part is measuring a child’s ability to memorize. Secondly, we can prove in other ways that our approach has value not measured by tests. For instance, one part of our learning program requires up to 45 minutes of “quiet reading” daily. Any reader knows that the way to get better at reading is by doing it more. Traditional high schools never set aside time in the day for personal reading. A year after we started quiet reading time, our reading scores went up. Our kids take all the tests and meet the state standards, but they go about it very differently.

Getting To Know You: Doug Thomas

Hometown: Henderson, born 12/9/1952.

College: Bemidji State University, B.S.; Minnesota State Univ., M.S., in Educational Leadership.

Married: Dee; children are Erin, Hope, Joshua, Robert.

Organizations: Co-President of the Henderson Chamber of Commerce; President of Community Capital (Henderson); President of New Leaf Development (Henderson); Member of the Minnesota Rural Education Association; Member of the Minnesota Association of Charter Schools.

Type Cast And Pegged

“I’m a raging ENTJ, just foaming with ideas and wanting to put them into practical use.”—Doug Thomas, EdVisions Cooperative.

The “ENTJ” is one of sixteen human personality types identified by Isabel Myers and Catherine Briggs, creators of the “Myers-Briggs Type Indicator” personality inventory.

From www.personalitypage.com: ENTJ’s are natural born leaders. They live in a world of possibilities where they see all sorts of challenges to be surmounted and they want to be the ones responsible for surmounting them. They have a drive for leadership, which is well served by their quickness to grasp complexities, their ability to absorb a large amount of impersonal information, and their quick and decisive judgments. They are “take charge” people.

They are very career-focused and fit into the corporate world quite naturally. They are constantly scanning their environment for potential problems that they can turn into solutions. They generally see things from a long-range perspective and are usually successful at identifying plans to turn problems around—especially problems of a corporate nature. ENTJ’s are usually successful in the business world, because they are so driven to leadership. They’re tireless in their efforts on the job and driven to visualize where an organization is headed. For these reasons, they are natural corporate leaders.

© 2005 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.