Kenway Engineering

Burgeoning manufacturer of air conditioning units for off-road vehicles reaches yet another fork in the road

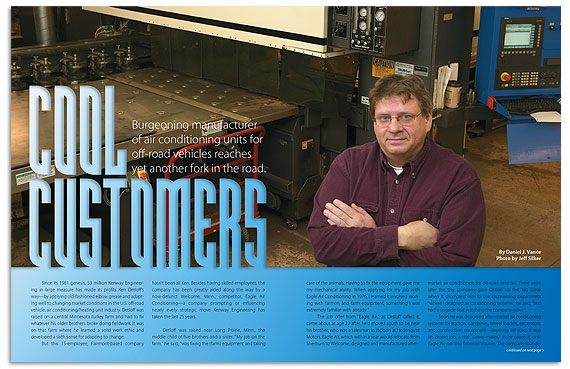

Photo by Kris Kathmann

Since its 1981 genesis, $3 million Kenway Engineering in large measure has made its profits Ken Detloff’s way—by applying old-fashioned elbow grease and adapting well to changing market conditions in the U.S. off-road vehicle, air conditioning/heating unit industry. Detloff was raised on a central Minnesota turkey farm and had to fix whatever his older brothers broke doing fieldwork. It was on that farm where he learned a solid work ethic and developed a sixth sense for adapting to change.

But this 15-employee, Fairmont-based company hasn’t been all Ken. Besides having skilled employees, the company has been greatly aided along the way by a now-defunct Welcome, Minn., competitor, Eagle Air Conditioning—a company prompting or influencing nearly every strategic move Kenway Engineering has taken the last 25 years.

Detloff was raised near Long Prairie, Minn., the middle child of five brothers and a sister. “My job on the farm,” he said, “was fixing the (farm) equipment and taking

care of the animals. Having to fix the equipment gave me my mechanical ability. When applying for my job with Eagle Air Conditioning in 1976, I learned it involved working with farmers and farm equipment, something I was extremely familiar with already.”

The job offer from “Eagle Air,” as Detloff called it, came about at age 22 after he’d moved south to be near his brother, who was a salesman in Jackson at Hedenquist Motors. Eagle Air, which within a year would relocate from Sherburn to Welcome, designed and manufactured after-market air conditioners for off-road vehicles. Three years later the tiny company gave Detloff his first big break when it promoted him to the engineering department “where I designed air conditioning systems,” he said, “and had a ringside seat watching the company grow.”

Soon he was designing after-market air conditioning systems for tractors, combines, wheel loaders, excavators, and construction equipment—anything off-road. It was his dream job, a real “career maker,” as he called it, until Eagle Air ran into financial trouble. The company founder sold his business to a Twin Cities holding company that would lay off Detloff and others. He had no idea what to do, where to go, whom to contact.

“I was living in Welcome, had been married only a month, and had three kids,” Detloff said of being unemployed. One good thing: his finances weren’t terribly pressing him because wife Barb had a job and he had a second job working on a farm. So he decided to strike out on his own. He approached the bank in Welcome and received a $1,500 loan to start Kenway Engineering, which meant he would be competing with his former employer. Rather than custom design and manufacture air conditioning systems, like Eagle Air, he would do design work only and outsource much of the manufacturing to Jones Metal in Mankato. That way he would incur relatively few upfront expenses. All he needed to do was find customers.

“I knew that county (governments) were buying air conditioners,” he said of his first week in business. “They were just starting to upgrade their off-road equipment to include air conditioning, and all of them had wheel loaders and motor graders. So I did a numbers game. I got a zip code book, got an atlas to find the county seats, and mailed out 1,400 letters in nine states addressed to ‘County Highway Engineer.’ I figured if I could get one percent, I’d be successful.”

Amazingly, the scattergun approach worked. The first two counties signing up were Dodge in Minnesota and Adams in Nebraska. The following year came several Iowa counties. Signing up counties wasn’t always easy. He remembered visiting the county building in Floyd County (Iowa) and peering up at its imposing three stories, as if it represented the odds against his winning the bid. On the third floor, he interviewed with all the county commissioners, who asked about his customer base and years of experience. In the back of his mind, he was worrying about being able to continue in business should the commissioners turn down his bid. Fortunately, they didn’t.

What he did well was sell and install quality air conditioning systems for about $2,000 each, about four thousand less per unit than what vehicle manufacturers charged for upgrades. He personally manufactured the mounting brackets that connected his air conditioning systems to the vehicles, custom designed each system on paper, and hired Jones Metal to build the cabinets. The easier final touches he could accomplish on-site, such as cutting hoses to length. Jones Metal helped a lot, he said, by making product for him on demand. He tried keeping a lid on his travel expenses by meeting only once with county foreman and engineers, and taking photographs for later review. Working on a tight budget, he couldn’t afford many quote or parts mistakes. In time he learned that chatting with the shop foreman about the equipment made winning bids much easier.

He said, “All I needed was an opportunity to prove to my customers that I could do what I said I could do.”

By 1986, Eagle Air and Kenway were really knocking heads as competitors. Just as Kenway Engineering was starting to take off, Eagle Air asked it to join hands with them by becoming an Eagle Air distributor. In other words, they wanted to replace the role Jones Metal and others had been filling. “Rather than fight, they were asking, ‘Why not join up with him?’” he said.

In mulling over their offer, Detloff faced staunch opposition from an unexpected source: his wife Barb. She argued that Kenway Engineering had been doing well enough without Eagle Air—and she further reminded Detloff, to no avail, that Eagle Air had been the same company laying off Ken just after their marriage. He didn’t budge. He felt the lay-off had been a business decision and nothing more. And Eagle Air’s offer to partner did seem awfully tempting.

“I viewed that move (of partnering with Eagle Air) as one of eliminating a competitor,” he said of it. “After doing that in 1986, we were able as a family to become fully independent of any outside income. Barb no longer had to work outside the home and I didn’t have to farm. I could give all my attention to the business.”

And so he did. He was custom-designing systems, manufacturing his own brackets, purchasing complete air conditioning units from Eagle Air, and installing and repairing them. His primary customers were dealers like Ziegler’s, which sold off-road vehicles and hired Kenway Engineering to install air conditioning units.

The relationship between Eagle Air and Kenway Engineering flourished until 1996. Along the way, both companies prospered financially. Eagle Air was up to 70 employees. It was bursting with orders from national accounts like Komatsu and couldn’t keep up with demand. With the vibrant growth, it was becoming more and more clear to Detloff that Eagle Air couldn’t meet Kenway Engineering’s demand. Its orders and design requests often were being placed on cold back burners, and the delays were hurting Kenway’s relationships with customers.

“Essentially, [Eagle Air and Kenway] reached a fork in the road,” said Detloff. “They were more and more reluctant to design the components we needed. At the same time, we were beginning to realize that history repeats itself. Remember when consumers purchased cars without air conditioning and had after-market air conditioning units added? It wasn’t long then before almost all the cars had factory air conditioning. We realized it was a matter of time before the same would happen with tractors and combines—all having air conditioning installed at the factory. And then we would be out of business.”

In 1996, Kenway Engineering began gearing up to manufacture air conditioning systems, thus competing with Eagle Air again. Detloff’s long-term goal was to exit the fast-vanishing after market by selling air conditioning units directly to original equipment manufacturers. Even General Motors didn’t build its own air conditioning systems, he said. He soon found a customer in Clarion, Iowa, in Hagie Corporation, which manufactured field sprayers. Terex Corporation of Waverly, Iowa, which built hydraulic cranes, came next. Then Kenway Engineering sales really took a steep growth curve after an Ohio-based company purchasing Eagle Air in the late ‘90s made a huge tactical error. It was a family owned business with everything else based in Ohio and didn’t particularly like managing a 70-employee Eagle Air plant out on the Minnesota prairie. The word on the street was the Ohio company didn’t understand the Eagle Air product line or its customer. It then took the company three months to move its machinery and office furniture to Ohio, and in that three-month delay Eagle Air “kind of put all their customers on hold, including us,” said Detloff. “They lost a lot of customers (in those three months). When you order an air conditioner in May, and you tell them August, that customer is gone.”

Kenway Engineering, in a short time, won over many of Eagle Air’s unhappy accounts. Then Eagle Air went belly up. In 2000, Kenway Engineering purchased sheet metal equipment and a powder paint system and became fully independent of needing any other air conditioning companies for parts.

So in summary, Eagle Air had hired Detloff, trained him as an installer and designer, laid him off, competed against him, become his supplier, in advertantly sent customers his way when they moved and went under—and finally, provided him for the rest of his life with a number of textbook examples of how not to manage a business. “I’ve learned in business by seeing what other companies do,” he said. “Sometimes you learn from them what to do, but sometimes, and more importantly, you learn what not to do.”

Today, besides Hagie and Terex, Kenway Engineering’s larger customers are air conditioning giants Bergstrom and Red Dot, which Kenway does niche business with in areas where the companies lack financial incentive or expertise. Illinois-based Bergstrom has been a premier builder for Caterpillar’s factory unit, and through it a buyer of thousands of Kenway mounting brackets. Seattle-based Red Dot buys similar products. The mounting brackets attach to an engine that supports an air conditioning compressor.

On the other hand, Hagie and Terex buy Kenway Engineering’s complete, proprietary system. The company has many smaller proprietary product customers scattered throughout the Midwest, including Jarraff Industries of St. Peter. One of Eagle Air’s former customers, Komatsu, now buys parts from Kenway.

“Our main niche is with smaller (OEM) companies wanting five or ten (units) a week,” he said. And a solid niche it has been: Detloff wasn’t aware of any competing companies that would be “good fits” for his off-road customers, except perhaps a Nebraska company doing “some of what I do,” he said. Although receiving inquiries to expand business internationally, Detloff has preferred staying close to home. He has politely turned down all international offers because he felt he wasn’t ready for that type of expansion.

Now Kenway Engineering, and the industry, appear to be on the cusp of accepting and manufacturing what Detloff referred to as “plug and play” units. Most multi-million dollar off-road vehicles today roll off the assembly line with factory air conditioning, and fixing those units in the field can cost operators thousands of dollars in downtime—much more than the expense of a new air conditioning system. “What I want to do is promote to these (OEM) companies a ‘plug and play’ system where they can just quickly change out the entire air conditioning system, like you would a window air conditioner out of a window, and plug in another.” Companies could then purchase extra air conditioning units, warehouse them, and take them as replacements to job sites as needed. They could pull the broken one out and plug in the new. The broken unit could be repaired and put back into service another day.

He said, “It makes sense for companies with different kinds of off-road equipment to have a common air conditioning unit so they won’t have to inventory so many different parts. I’m working on customers right now to make that more popular. Someday maybe that will be standard equipment. That’s where the future is.”S

On Seeking Capital For Growth

It’s obvious you have to have a track record with your bank. We view our bankers as consultants as well as a money source. You have to have the balance sheets and the capability to pay it back. And your financiers must believe in you. I work with banks in Fairmont and Welcome, the latter the first bank I had. They have helped me out tremendously and I’m very loyal to them. — Ken Detloff, Owner.

What Is Your Job?

If anyone has to go on the road, I tend to do that, whether installing or designing. Overall, I see myself as the more creative force at Kenway Engineering. I look at customers to size them up, to see if they’d be good matches. I come up with new designs, and concepts in air conditioning. Ours has been a family style company. We have very good people. I’m here pretty much every day by ten or am working on the road. Quite frankly, the company could run without me for a long time. I have that much confidence in our people. — Ken Detloff, Owner.

Future Tense

Most of Kenway Engineering’s air conditioning units sell in the $1,000-$3,000 range, with hydraulic units priced the highest. The company in 2005 had more than $3 million in gross revenues.

“We do for [many of our customers] what they don’t want to do for themselves,” said Ken Detloff, owner. “One of our best niches is in hydraulic-driven units. In our world (of mechanical engineering), there are engineers trained in hydraulics, and then there are engineers trained in air conditioning. We blend the two together. That is our niche.”

As for challenges, their biggest in 2006 involves changing the company mindset from one of being reactive to proactive. Above all, Detloff desires to keep his current customers happy, a lesson learned from watching Eagle Air’s miscues, and better planning and intuition concerning customer needs will greatly help.

“Our old software was designed for distribution,” he said, “and we struggled with it a number of years. With it, we had no capabilities to schedule product through our shop. We were just winging it and knew we had to change. Our biggest challenge this year is we have all new manufacturing software. We need to understand and use it the way we need to use it, and to learn to plan production to satisfy our customers. Once we have this internal issue solved, then we can take on bigger customers. With our new software, our customers can order online, check accounts, place purchase orders, and lease product.”

Labor’s Day

“I do have a good group of employees in terms of talent and productivity,” said Ken Detloff. “We wouldn’t go anywhere without them and I owe a lot of credit to them.”

Having said that, he admitted not all was well in hiring.

“I have a concern in our future about our employees,” he said. “I look at them and don’t see many young ones. Small towns in general tend to be losing them. I look around at other [businesses in small cities] and see the same thing. We as a community have to turn that around to keep our younger adults here at home.”

He seemed a bit puzzled why. The wages he paid in Fairmont for skilled labor were $12-$15 per hour, which compared quite favorably to the $17-$18 per hour often offered in Minneapolis, especially factoring in the latter’s threefold higher housing costs. Or, he speculated, the pull to the Cities for younger adults could be cultural or social.

As for Kenway Engineering, the company had in 1996 only five employees. Today it employs 15 and more will be arriving. Detloff has hired three former employees of Harsco Track Technologies, formerly Fairmont Tamper, which has struggled the last decade. Two of his engineers, Ray Carlson, a former Eagle Air employee, and Dan Henning, are Minnesota State University mechanical engineering graduates.

© 2006 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.