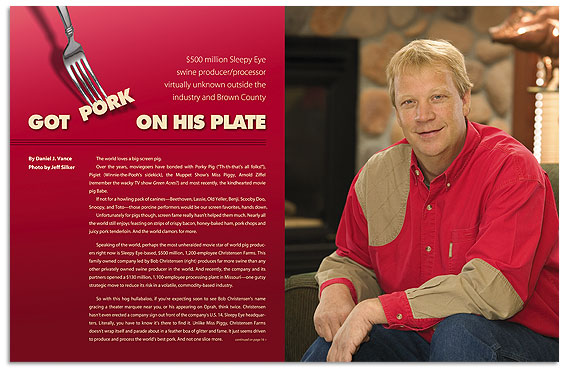

Bob Christensen

$500 million Sleepy Eye swine producer/processor virtually unknown outside the industry and Brown County

Photo by Jeff Silker

The world loves a big-screen pig.

Over the years, moviegoers have bonded with Porky Pig (“Th-th-that’s all folks!”), Piglet (Winnie-the-Pooh’s sidekick), the Muppet Show’s Miss Piggy, Arnold Ziffel (remember the wacky TV show Green Acres?) and most recently, the kindhearted movie pig Babe.

If not for a howling pack of canines—Beethoven, Lassie, Old Yeller, Benji, Scooby Doo, Snoopy, and Toto—those porcine performers would be our screen favorites, hands down.

Unfortunately for pigs though, screen fame really hasn’t helped them much. Nearly all the world still enjoys feasting on strips of crispy bacon, honey-baked ham, pork chops and juicy pork tenderloin. And the world clamors for more.

Speaking of the world, perhaps the most unheralded movie star of world pig producers right now is Sleepy Eye-based, $500 million, 1,200-employee Christensen Farms. This family owned company led by Bob Christensen (right) produces far more swine than any other privately owned swine producer in the world. And recently, the company and its partners opened a $130 million, 1,100-employee processing plant in Missouri—one gutsy strategic move to reduce its risk in a volatile, commodity-based industry.

So with this hog hullabaloo, if you’re expecting soon to see Bob Christensen’s name gracing a theater marquee near you, or his appearing on Oprah, think twice. Christensen hasn’t even erected a company sign out front of the company’s U.S. 14, Sleepy Eye headquarters. Literally, you have to know it’s there to find it. Unlike Miss Piggy, Christensen Farms doesn’t wrap itself and parade about in a feather boa of glitter and fame. It just seems driven to produce and process the world’s best pork. And not one slice more.

You began in business in 1974 at age 9?

I grew up on a cattle and row crop farm. A neighbor gave my brother and I two bred gilts to get started in swine production. Prior to that, our family hadn’t had any significant production. In the beginning, I didn’t know anything specific about swine, but having cattle did provide us with the basics of animal husbandry. By my high school graduation, I had 150 sows, which at that time was one of the largest sow herds in Brown County.

The real turning point for our business came in the mid-’80s during the farm crisis when many hog facilities suddenly went empty. The financial community wouldn’t lend farmers the money to buy feeder pigs. That caused us to change from a philosophy of growing baby pigs all the way to market to one of taking them off the farm at 40-50 pounds to neighboring facilities and paying those producers a yardage rate. That phenomenon really picked up in 1985-86 as the farm crisis was at its worst.

You said once that when the swine production industry is going bad, that’s when you go full throttle; and when it’s good you put on the brakes.

Generally that’s true. However, it’s difficult to completely put on the brakes when you have a talented infrastructure wanting to grow. But whether liking it or not, we are in a commodity business. At this point in the hog cycle we are being a bit more cautious than many of our peers. Right now the probability of good revenue and prices over the next three years is much lower than it was three years ago. Back then we had just come out of three years of poor revenue.

How large is Christensen Farms?

We have 1,200 employees, and are part owners of a processing plant employing another 1,100. We have 440 contract producers, and up to 800 independent contractors in feed trucking, animal trucking and other roles. Christensen Farms raises enough fresh pork to feed more than 12 million people annually—about three million pigs a year. I believe we are the largest privately held swine production company in the U.S. and world. Our gross revenues vary wildly because we’re in a commodity business, but right now we’re a little shy of $500 million.

After many years of not being in the public eye—though well known in the industry, you are almost unknown outside of Brown County—why do it now in Connect Business Magazine?

Unlike some of your peers at newspapers in the region, you are fairly accurate and realistic about business. Quite frankly, there is little written about us in newspapers in southern Minnesota because many of them are more inclined to focus on isolated, negative things in our industry. And they haven’t been able to find a whole lot of bad about us.

Your industry has had bad press the last ten years, perhaps not here as much as places like North Carolina. Do you feel sometimes that your company gets blamed for what they have done?

Reading negative press about the swine production industry was common six or seven years ago, but those types of stories have dramatically dropped off for a number of reasons. Today, manure is collected under barns in concrete structures and injected below the soil surface, considerably reducing odor. People generally understand that manure is a valuable resource that can be put back on the land to raise next year’s corn crop, and to have residual phosphorus and potash for the following years’ soybean crop. Manure is a valuable renewable resource. It’s harder to find a use for manure in fringe areas of hog production that have less cropping. For instance, producers in North Carolina and Missouri tend to put the manure on grassland and then bale off the grass. Here in Minnesota and the Midwest, we can inject the manure underneath the soil surface to eliminate odor and runoff. The corn crop planted next spring takes up the nitrogen, phosphorus and potash.

Christensen Farms in 2002 purchased ValAdCo, a large Minnesota swine producer with a very bad reputation. What was its problem? And why purchase such a troubled company?

Before buying, we spent considerable time talking with its neighbors to learn what was really happening firsthand from the people experiencing the negative effects. There had been so much emotion about the company prior to our taking ownership. After buying, we made a number of substantial changes. At one facility we downsized a lagoon that was too large. At other facilities, we turned lagoons into wetlands. We ended up investing close to $2 million to reconfigure waste handling. One factor in that company’s pollution problem was its nutrition—if you’re feeding hogs too much, the amino acids and protein just pass through and emit an odor. If feeding only what the pig uses up, you don’t have as many elements to create odor.

What motivated you to take on such a troubled business?

It was clear to me the company could be fixed. During Gov. Ventura’s term in office, the state had a pollution control agency that felt its job was to say no to everything swine producers did. But in buying ValAdCo and trying to fix the situation, we were supported by the attorney general’s office, which was instrumental in helping us bring forward logical solutions and to get those solutions through the agency and through planning, zoning and environmental offices. Back then, everyone seemed polarized. The existing ownership of ValAdCo couldn’t have done anything right even if they had been right.

We haven’t heard any complaints from the neighbors the last two years. We extensively monitored the former ValAdCo facilities the first year after the remediation and passed all the standards contained in our agreement with the attorney general’s office and the state pollution control agency.

What technology is being developed to reduce odor?

There are tremendous efforts out there. But at the end of the day, reducing odor really comes back to the solid basics of feeding the pig right, and not having waste out of the feeder and into the effluent. It’s important to get that manure handled, hauled and onto the crop land each year, using it as a resource rather than a hindrance. The ValAdCo facilities, in my opinion, were not properly emptied out. In remediation, we got out all the accumulations from the prior six years onto cropland to grow corn. It wasn’t there to create an odor in the spring. We have six full-time agronomists managing manure storage and application.

Why are U.S. pork exports rising?

For one, U.S. pork is healthy, the healthiest in the world. Go to any other country in the world and none of their pork will surpass ours in terms of how the pig is raised, processed, the standards it’s processed under, and the various inputs allowed or not allowed to raise pigs. Our story is about quality and consistency. In the U.S., we have achieved it through right nutrition, right facilities, proper processing, and genetics. We aren’t doing anything that complicated in the U.S. We’re just doing it right on a wide scale. We have a handful of processors, ourselves included, who have spent the time to economically bring forth a wholesome product. We can do this for much less cost to the consumer than can be done in Europe and other parts of the world.

Hasn’t the weak dollar bolstered exports?

No question about it. But U.S. exports would have risen even without a weak dollar. Let’s say the dollar has added a level of robustness that wouldn’t have been there. Another huge factor driving exports is a world economy growing stronger and stronger. Each month, more and more people can afford to buy the food products they need.

Why are swine producers becoming processors, and processors becoming swine producers?

We’re in a commodity business whether we like it or not, one that has cycles of supply and demand. When the “live” (swine producing) side of the industry is flourishing, the processing side is suffering. When the processing side is flourishing, the live isn’t. By combining the two, you take out much of your volatility.

But by being involved in processing, which Christensen Farms now is with a new $130 million facility in Missouri, don’t you risk ticking off large processors like Hormel? Won’t that hurt your relationship?

The good share of our partners investing in our Missouri processing plant eventually will take all their pigs there. It’s true we are a substantial customer to Tyson, Excel, and Swift. But those relationships can be managed.

What about those larger processors getting into swine production?

That’s fine with us. They won’t match our levels of productivity and efficiency. Most states have corporate farm laws to stop processors from doing this. But then the processors go to states that don’t have those laws.

Who has financed the growth of Christensen Farms?

A good share over the years has come from the farm credit system, which has evolved into the present-day AgStar. Currently, our credit facility includes a number of banks. Due to healthy revenues the last few years, it’s relatively easy getting financing. The real key in our picking a banking partner is having them understand the volatility of the industry. Rural Minnesota has a number of great banks, but we usually can’t work with them because of the size of our credit facility.

Who financed you early on?

Our parents helped a little bit on the front end. We were 50-50 partners with them early on. Then that evolved into my brothers and I having more ownership. We completely bought out our folks a couple years ago. Today it’s just me and my brothers Lynn and Glen owning company stock. I’d say the farm credit system, and a couple of insurance companies and commercial banks, have been supportive of us through all the ups and downs. They understand swine production. They understand Christensen Farms. They are there in the good times and the bad.

You’ve done so well, and yet others starting out in similar situations haven’t. What makes Christensen Farms different? What makes you different personally?

We focus on what is important. For instance, feed is responsible for almost 60 percent of the cost of raising a pig. Unlike most other swine producers, we make all our own feed. We buy the ingredients just as a feed company would and we put them together.

Consolidation in hog production was driven by a handful of things. For one, feed companies were taking huge margins. The key word here is “were.” They aren’t able to take those kinds of margins today because buyers are more sophisticated. Consolidation was also driven by genetics. From our own perspective, the success of this company is based on a handful of things. For one, our location is a positive: we have low-cost corn and soymeal; we have a Midwestern work ethic—the talent here is the best in the business; and we have many markets to sell to.

What makes Sleepy Eye a good location?

Southern Minnesota and northern Iowa is a great place to raise hogs. You have all this corn and soybean land to put the effluent on. You need the corn and soybean meal for feeding the pig. People want to talk about sustainable agriculture—the fact of the matter is that swine production here is a most efficient and sustainable cycle. The corn makes the hog, the hog makes food, and the manure goes on the land to raise a crop again.

As for other components of our success, clearly, the topmost has been our ability to find, attract, and retain high-quality people at all levels in the company. In the last few years a great portion of the key talent entering the company has come about through word of mouth from someone already working here. Other new employees have known past co-workers, or friends or family here.

Sometimes it can be difficult recruiting talent to Brown County. I would be less than truthful if I said we hadn’t had candidates we’d really like to have—and they’d really like to work for us—but they don’t want to live here. Often we just have to work a little harder to find the right fit.

Let’s discuss Triumph Foods. In the last five years Christensen Farms has made two major moves. One was moving forward with Triumph Foods, a $130 million, 1,100-employee processing plant you began in Missouri. You ended up partnering there with four other swine producers.

Clearly, we’re one of the largest partners in Triumph Foods. It was never our desire to be involved in hog processing. I really enjoy more the farm, the live side. But the commodity volatility of selling live hogs to the Hormels of the world—frankly, it’s their job to buy from us cheaply as they can. When supply was more robust, such as in late 1998 and early 1999, hogs were lower than 20 cents. Yet the processing margins were unbelievably high.

The “live” side accounts for about 78 percent of the capital investment in getting a hog from birth to market. (It accounts for about 50 percent of the human investment.) From a capital standpoint, we began realizing we were only 22 percent away from completing the food chain. It was then I realized we had to focus on completing it. It took just five years and four months after making a decision to build our own processing before we killed out first pig in January 2006.

How did you build a plant from scratch?

Many swine producers no doubt would have focused first on finding the talent and people. My focus, which was shared by other partners, was to find the best CEO we could find, set the company up as a separate entity, and allow that CEO to build a management team to design the plant and run it. In my opinion, we hired the best person in swine processing, Rick Hoffman. It took almost a year to persuade him to come out of the company he was in, in order to do a “green-field” start-up. For a couple years, Christensen Farms went at it alone until Rick and I found other partners. All the partners had been familiar with each other long before we built the plant.

Having our own processing plant will take much of the volatility out of our business. It also allows us to become integrated. For instance, if wanting to improve meat quality, sometimes a plant could do it but for 25 cents. That same improvement could be done on the live side, but for a dollar. It could be done either place. Some processors have a business strategy of pushing off that improvement to their live side suppliers, until the suppliers are almost broke, before easing up. By being both producers and processors now, we make those types of improvement decisions based on what makes the most sense to get the objective accomplished.

Can you give a more specific example?

One would involve meat quality and color. In a new plant, using the capability to chill, cool, and equilibrate a carcass, you can affect your meat quality hugely. Or you can have the same effect on meat quality and color by using a different genetic line that doesn’t grow as fast, one that takes a little more feed. In other words, you can do it for little or nothing at the plant, or you can do it on the live side for a sizable expense. Another example would involve having a yard large enough to rest the hogs four or five hours before processing. This enhances meat quality. Again, you can get that meat quality using genetics or nutrition, or you can get it at the plant. In many cases, processors push that end product desired by the consumer onto their suppliers. Yet it can be done at the plant more economically.

When searching for a Triumph CEO, what traits were you looking for?

I wanted someone who’d already built and started up a plant. Rick had done that twice. Secondly, I wanted someone with a diverse skill set. I wanted them to have a good understanding of legal and accounting. I wanted someone driven and persuasive enough to bring in other talented people to complete the team. Most importantly, I wanted a leader and team builder.

How much is he like you?

Rick is very upbeat and can-do while I’m more reserved. At first blush, almost every idea is a good one to him. I’m more skeptical. Yet, he does become skeptical before attempting to apply new ideas. Rick and I are both very driven.

When that plant started January 3, you were there when the first hog went through. What sort of emotions and thoughts came over you? Were you handing out high fives?

There was a little of that. But even after the opening, we still had a lot to figure out. I didn’t begin to feel confident, in the sense that plant would exceed our expectations, until the last weeks of February. A month before starting the plant, we had about 50 people on payroll. Fifty-five days later we had 1,100.

American swine producers are building facilities in Brazil, Mexico and Eastern Europe. Have you thought of going there, alone or with other producers?

Certainly. I’ve been to South America a number of times. Going there for a pilot project is potentially not that far off in our timetable.

What makes going there advantageous?

It would be a more defensive than offensive move. I see fewer opportunities here in the States. One large factor is the cost of building infrastructure. With China taking off economically the last five years, the price of steel and cement has risen. Quite a few swine facilities will be constructed this summer, and I’m concerned about long-term competitiveness because of this kind of cost.

Here’s an example. The spaces we finish pigs in, to take them from 50 to 270 pounds, cost about $145 each. Facilities built this summer, because of higher prices, will cost $220-240 per space. I’m skeptical of the long-term competitiveness of those facilities in the world or domestic market. Labor is another cost. Here in the United States, we are evolving into a country that wants to be served. We don’t want to do the hard work anymore.

What one trait upsets you most when you see it in an employee?

What hits my radar screen strongest is seeing someone settle for less than what is possible. For instance, seeing someone happy with nine when ten pigs were possible from a litter. Or someone that settles for getting 240 loads of feed out of here when 270 were possible. I like people striving for 100 percent. You’re not always going to hit the 100 percent mark, but effort is most important.

Quite frankly, revisiting your question concerning the success of this company, we don’t have many people not giving their all. Everyone wants to do his or her best.

Heartland Pork Enterprises (of Iowa) was the nation’s thirteenth largest swine producer when you bought them in 2004. Could you take me through how and why you acquired them?

I think the ownership of Heartland Pork, and its banks, were very interested in selling the company for a reasonable price. The three years prior to that the industry on the whole had made virtually no profits. After that extended period of poor returns, I thought Christensen Farms only had to stick it out a little while before the industry would get better. We made an arrangement with the banks and owners of Heartland Pork for 35-cent hogs, and when we closed 60 days later the hogs were 55 cents.

Heartland Pork also fit geographically. It didn’t have any substantial environmental challenges—very different from ValAdCo. The company was relatively well run. But it did have a disadvantageous sales contract with a packer. We now have a presence in the marketplace. We are the only Upper Midwest producer that processes a good share of its own hogs, and sells a substantial portion of hogs to Tyson and Swift. We have multiple markets. Historically, we were huge customers of Hormel, but that changed in the last year when we put in our own processing plant.

Where will Triumph Foods’ product go?

It will be one of the highest percentage plants in the U.S. for export. About a quarter of it will go to the Pacific Rim and some to Mexico. It’s a bit risky to build a business platform too much beyond that percentage in exports. Domestically, our product will go to the South and Southwest. We are not interested in selling to Wal-Mart or Sam’s Club, or to large grocery chains. In my opinion, if a company announces a big agreement with Wal-Mart, you should probably short their stock.

When talking to people outside Brown County, most haven’t heard of your company. Yet $500 million is a large company. I’d bet many people even in New Ulm have no idea Christensen Farms exists.

Our purpose isn’t to be well known. Our purpose is to raise the healthiest food product we can. Our purpose is to be better at what we do for the people growing with us. The notoriety isn’t that important.

SWINE JET

Our airplane is like any other business tool. It has allowed us to get more out of key management people. By using the airplane, they can be home at night. We sometimes have to fly 500 miles west of here to Nebraska to a pod of production with a couple hundred employees. We also have similar destinations in Missouri, Iowa, and Illinois. All those are a minimum of a five-hour drive one way. With a plane we can leave New Ulm in the morning, be somewhere in 75 minutes, put in a day, and be home for dinner at seven. In the past those trips would have taken two days, and you’d be exhausted on the third day because you’d just driven ten hours. — Bob Christensen, Christensen Farms.

DEFINITION

Equilibrate: The carcass goes through a blast chill at 35 degrees below for 105 minutes. The outside is frozen hard, like a football helmet, yet the inside remains somewhat warm. The carcass goes into bays for 12 hours where the outside begins to thaw and the inside falls in temperature. So it all equalizes. Then the meat is ready for cutting and packaging. – Bob Christensen

CONNECT FACT:

Christensen Farms employs in Sleepy Eye alone over a dozen PhDs and DVMs. Also, each year it consumes more than 28 million bushels of corn and 12 million bushels of soybeans.

© 2006 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.