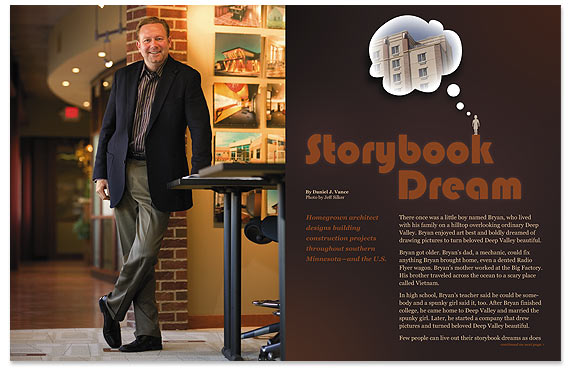

Bryan Paulsen

Homegrown architect designs building construction projects throughout southern Minnesota—and the U.S.

Photo by Jeff Silker

There once was a little boy named Bryan, who lived with his family on a hilltop overlooking ordinary Deep Valley. Bryan enjoyed art best and boldly dreamed of drawing pictures to turn beloved Deep Valley beautiful.

Bryan got older. Bryan’s dad, a mechanic, could fix anything Bryan brought home, even a dented Radio Flyer wagon. Bryan’s mother worked at the Big Factory. His brother traveled across the ocean to a scary place called Vietnam.

In high school, Bryan’s teacher said he could be somebody and a spunky girl said it, too. After Bryan finished college, he came home to Deep Valley and married the spunky girl. Later, he started a company that drew pictures and turned beloved Deep Valley beautiful.

Few people can live out their storybook dreams as does Bryan Paulsen, founder of Paulsen Architects, a 25-employee, Mankato-based architectural design firm. His lifelong abilities to boldly dream and draw, especially the last 13 years, have helped create what is speedily turning into a critical mass of architecturally beautiful buildings for southern Minnesota. Even if retiring this minute, 51-year-old Paulsen leaves an architectural footprint for future generations in eleven states, and in New Ulm, Mankato, North Mankato, Fairmont, St. Peter, Blue Earth, Sleepy Eye, Springfield, Madelia, Wells, Minnesota Lake, Winnebago, Pemberton, Janesville, Madison Lake, St. James, Le Sueur, Lake Crystal, and Waseca.

In a way, his life has been storybook. Marrying his high school sweetheart. Owning a business. Expressing his passion. Changing his world. Turning beloved Mankato and southern Minnesota beautiful.

There once was a little boy named Bryan.

Where did you grow up?

I’m a homegrown kid. I grew up in Mankato and graduated from Mankato East in 1974. When I was a young boy we lived on Mayfair Drive on the hilltop (off Main Street) and then in 1971 our family built a house in the country between Mankato and St. Clair. At Mankato East, I really enjoyed an architectural drafting class with teacher Rocky Schoenrock during my senior year. He encouraged me to go into architectural drafting as a career. At the time, I didn’t understand the difference between being a drafter and an architect.

What is the difference?

To become an architect, a person typically goes through an accredited university program and eventually gets their professional license to practice. A person taking the drafting route usually goes to a technical or community college. In drafting, a person doesn’t get an opportunity to become licensed, yet can still become part of an architectural team. It’s similar to the difference between accountants and CPAs. During my senior year of high school I had to make a decision about what to do in life. At the time I was dating the girl who would eventually become my wife, Tami, and she urged me to consider pursuing a career as an architect. I decided I wanted that route. However, I wasn’t sufficiently prepared academically to gain admittance to an accredited college architecture program. I wanted to attend the University of Minnesota School of Architecture, but first had to go to college to gain my pre-architecture requirements, which would take about two years. I enrolled at Mankato State and took general coursework and a lot of math classes including algebra, trigonometry and calculus—classes I should have taken in high school. In order to complete the pre-architecture requirements in two years, I ended up having to take way beyond full load at MSU.

Most people wouldn’t have played two years of catch-up. What was there about architecture that drew you?

I realized how much I loved it—and I wanted to be a licensed professional. That was my motivation and even after those two years of courses at MSU I still didn’t know if I’d be accepted into the U of M School of Architecture. It wasn’t a given because I still had to apply and be selected from a competitive pool of applicants.

Did your desire for architecture come from your parents?

My dad was a mechanic for the Blue Earth County Highway Department and my mom worked in an electronic assembly manufacturing plant. They could build and fix anything. My dad taught my brothers and I how to fix engines, weld, solder and build. My father thought very analytically—his mind was like that of an engineer. He taught us early on about problem solving and much of architecture is about problem solving.

Tell me about your first date with Tami. You two have very different personalities.

We are different, which is probably why we make a good team. I first met Tami when my friends and I were playing pinball at Victory Bowl. We were playing enthusiastically, as guys do, kind of banging and hitting the machine to win free games, and this girl walked up and said, “Hey, stop that—my dad owns this machine.” (Laughter.) That’s how we met. I was a high school senior and she was a sophomore. Our first date was a movie, and Tami brought along her friend Diane.

What has Tami done for Paulsen Architects?

She started here about ten years ago after she had worked 18 years in her family’s business, C & N Sales. She has helped take us to our current level. Tami wears many hats. She has helped develop and enhance our business strategies, marketing strategies, publications, and proposals—all the things falling under the marketing umbrella. And she’s not only our director of marketing, but also our director of administration and human resources. When I started this company in 1995 and the company was very small I could do it all. But as we grew, and I was still trying to do it all, I started losing focus. I was not made to be an administrator; I was made to design, meet clients, and make presentations. Tami’s business and managerial experience really helped bring our company along. She was the seventh employee. We now have 25.

You went to college from 1974-82?

One reason it took eight years was because I first needed to complete two years of requirements before being accepted to the U of M. Then it took me longer than some students to get through because I wasn’t in a financial position to attend school full-time. I had to work my entire way through and pay for everything. While attending the U of M, I worked for architectural firms in part-time, entry-level jobs during the school year and full-time in summers. My first jobs involved building models, doing renderings, running errands, and drafting. I began working for AEI Design in 1979. At that firm, they really left a lot of design work to the architecture students. I was literally designing multi-unit townhouse projects as a college kid, from preliminary design through construction drawings, and coordinating the project in the field. I wasn’t a licensed architect, but was under someone else’s license—literally jumping into the profession feet-first. With that background, by the time I graduated I was far more experienced than most of my fellow students going through the traditional four- or five-year architecture program.

Where did you go in 1982 after college?

I moved to Mankato because Tami was living there and working in her family’s business. I went to work for what would become KSPA Architects and married Tami. I stayed there 13 years. Jim Kagermeier hired me, and was very nurturing and a great mentor. At the time I joined the firm they designed a wide variety of building types but were considered specialists in K-12 education.

If they had made you a partner, would you have ever started your own business?

I did approach them about being a partner and Jim did not seem interested in that sort of relationship. Jim’s son Jeff was also studying architecture and I believe their plan was that Jeff would eventually take over, which happened. So I had to make a decision about my future and in 1995 went out on my own. I felt Southern Minnesota was ready for a more creative approach to architecture—more focused on design. It wasn’t that KSPA didn’t do good design work, but I didn’t believe as a firm they were as creative as they could be in their use of different materials, technologies and delivery systems. Given the position I was in at KSPA, it was difficult for me to get them to change their model. There was just a big philosophical difference between how they operated and what I wanted to be as an architect and designer. I wanted to be able to explore other boundaries. Consequently, when I founded my own firm, I founded it on a philosophy of bringing bold design solutions to my clients, and today that’s still our mission.

Did your wife’s father, who owned C&N Sales, help your business get off the ground?

He did. He co-signed on a $50,000 loan with the bank so I could get started. I started the company on April 15, 1995, in the basement of my home. Greg Borchert, who is still with me, left KSPA to work with me. So now I not only had to worry about my own finances, but also I had Greg’s salary to deal with, too. I was down to my last couple thousand dollars in the bank when I got my first check from a client for design services. I couldn’t have done it without my father-in-law, Harlow Norberg, and his faith in me.

You must have admiration for Greg because he joined you when most people wouldn’t have taken that risk. What do you think he saw in you?

Oh, there was risk for Greg. At KSPA, I had become over time a ‘front person’ for the firm. I made a lot of the presentations, client contacts, and brought in a lot of new clients. I think Greg saw that. What I saw in Greg was his strong technical and project management ability. He has a tremendous understanding of different building systems, how to put buildings together, and how to coordinate a project with contractors and consultants. In order to fulfill my vision to provide clients bold design solutions, I needed someone with Greg’s expertise who could help implement this vision. Really, he is the best there is in this field.

How can a good architect increase a company’s profit or customer base?

I believe good architecture and design can directly impact an organization’s success. The perfect example is the former Midwest Wireless headquarters, now Alltel. At first, Dennis Miller, their president, just wanted me to design a “box on a box” and call it good. Our design team kept coming back to him, saying, ‘But Dennis, the “box on a box” concept doesn’t fit the business model you’ve explained to us as being the way you want to function and operate.’ We developed an alternative design we believed met Dennis’ vision better and kept bringing that design back to him and his administrative team. Finally, they got it. When their new headquarters building was completed, the building itself became a huge recruiting tool. They had hundreds and hundreds of unsolicited job applicants, even in a tight labor market. People wanted to work in that building. The design of the building helped the company grow and succeed by meeting their employment needs and operating effectively to meet their vision.

Snell Motors is another example. Our challenge was taking an old Menard’s building and converting it into a state-of-the-art automobile dealership. Todd Snell’s vision for his dealership was different from the cookie-cutter dealership plans available. Todd had to convince GM to support his vision and then it was our job to design a plan to help him implement. We wrapped our architectural design around Todd’s concept and vision. Ultimately, the building has helped him advance his business model, company mission and vision, and sell more cars. Again, good architecture is all about understanding and listening to what your client is really telling you and then providing design solutions to meet their needs.

Of the buildings you’ve designed, can you name three professionally challenging ones?

The Intergovernmental Center in Mankato was the first large, multi-million dollar project we designed. It was really challenging. The Intergovernmental Center was built onto the end of the downtown Mankato Place mall after several alternative sites were analyzed. One challenge was how to create a facade of a government building attached to an urban mall so it looks like and has the character of a government building. Another challenge was how do you take that façade and integrate it into the mall’s structure? The new construction stops at the current lobby elevator and everything beyond that point is a renovation of Mankato Place. Aligning floors, continuity of materials, creating flow, transitioning from old to new and not make it look like you tacked something onto the front—these were the design challenges.

Another challenging project was the Hilton Garden Inn in downtown Mankato. One challenge was just convincing people the building would fit on the site. Another was blending Hilton Garden Inn specifications with an urban hotel model. Because of the location in our downtown it couldn’t be the typical prototype, three-story suburban Hilton Garden Inn on a five-acre site. We still had to work within the Hilton design standards, and when we deviated they had to approve everything. We also had to create a beautiful building that helped address the revitalization master plan for downtown Mankato. The net result is an iconic structure, and a successful project providing needed amenities. I think it is a wonderful addition to downtown Mankato.

Another project: Pub 500. We had a small corner site in a downtown, established urban setting. So how do you make a new restaurant and bar building and design it so it appears consistent with the existing fabric of downtown? Our design challenge was to architecturally treat the building so it looked like it always belonged there. We created the building to appear like there are two separate storefronts—like there were two different buildings joined together. We did that on purpose to break the scale of the building down so it was more consistent with other storefronts downtown.

You designed a unique entrance to Snell Motors. They eventually took it down. Why?

That was a General Motors decision. GM also wanted the color of the Snell sign changed from red to blue. Our original design had a tilted overhang that was an architectural gesture to break up the building’s symmetry, just a unique element to add a twist, literally. Our design team felt the building needed something more than just a straight and rigid canopy. Currently, GM is trying to get all its facilities to have some level of consistency. This decision came down quite a while after the building was constructed.

You’ve done many projects outside southern Minnesota. Are there logistical problems working outside the region?

We’ve completed many projects outside the region and in several other states. Our design professionals are registered in multiple states. Right now we’re doing work for Rasmussen College and designing their campus buildings throughout the U.S. The model we’ve created for projects outside of our immediate region has been successful and we’ve been able to deliver these projects through both the competitive bidding and/or design-build process.

What is AIA and your role?

AIA is the American Institute of Architects. It’s our national trade association and voice of the architecture profession. I’m a second-year director of the AIA Minneapolis chapter board. One of my roles is to help get greater Minnesota architects more involved in the organization. Because AIA Minnesota is made up of primarily metro area architects, there has been a big disconnect in the association between metro and outstate firms. The board asked me to help reach out to architects in places like Willmar, Hutchinson and Marshall, and have them get engaged—not just to pay dues, but also to become involved.

You live next door to businessman Bob Dale, and on the same street as Kent Schwickert (Schwickert’s), Phil Slingsby (Scheel’s), Todd Snell (Snell Motors), and Mike Brennan (Brennan Construction), to name a few. Have you ever been chosen for a project just by walking down the street and knocking on a neighbor’s door?

(Laughter.) No, but that’s not a bad idea. (Laughter.) A lot about being successful in business, and in our profession, relates to building relationships with people, and I have a relationship with everyone you named and have done business with them. In most cases they are repeat clients and have become my friends.

Do you have block parties or neighborhood gatherings?

Oh, yes we do get together. When we have neighborhood gatherings in many cases there is some level of business going on. People are asking, What’s happening out in the market? Given what I do for a living, sometimes I have a pulse on the future construction economy before even some of the contractors do. People are always asking, What’s going on? Or asking for advice.

Some engineering firms have architects on their payroll. Have you thought of being an architectural firm that employs engineers? Do you have an engineer?

We do have engineers. Five years ago we began providing structural engineering services. It was a business strategy to begin offering that type of service. We chose structural engineering because a certain percentage of our work is design/build and often in that model of delivery the only type of engineering service required is structural. Also, structural engineering is so closely integrated with the architecture of the building that having it in-house streamlines the design process and ultimately provides more efficient and effective design services for our clients. We have focused our business plan on being experts in the design of buildings so structural engineering fits that model well. I purposely have not wanted to bring mechanical, electrical, and plumbing engineering (M/E/P) in-house. That’s never been part of our strategy. The reason is that I don’t believe firms can do everything well. I believe a business should concentrate on what it does best. In the same vein, engineering firms offering all types of services can’t be the expert in every type of facility design, such as medical, education, corporate, retail, religious or public buildings. For instance, there are vast differences between M/E/P systems for a medical building or hospital and a K-12 school. So when we design these different types of buildings, we choose the most qualified M/E/P engineering firm for each particular facility type. We work with an excellent pool of engineering firms on a regular basis and put together the best possible team for each individual project. Doing it that way delivers a better project for clients.

In the 1980s, when starting out, you and Tami lived at Sixth and Rock in Mankato. Did you think then you’d be where you are at today professionally?

We married and bought that house in 1982, and lived there until 1991. That was a great house, an old Victorian, the former home of the Kato Brewery brew master. Tami and I completed renovating it. While there I was a principal architect with KSPA Architects. In 1991, when our son was born, and Tami and I decided to build a new home, I probably didn’t know then I’d be where I’m at today. But I was probably beginning to conjure up ideas about where KSPA or I should be going. I have to believe I was thinking then about how to make architecture in our community better.

I’ve read you do a great deal of pro bono work.

At our firm, giving back to the community and volunteerism is stressed and is a part of our culture. Several years ago, we became involved in a national effort called the “One Percent Solution.” This effort asks architects to pledge one percent of their billable time to pro-bono work for the public good. As an example, we’ve completed pro-bono work for the Miracle Field, Blue Earth County Historical Society, Twin Rivers Center for the Arts, YMCA, SMILES, and YWCA, to name a few. Right now we’re working with the Blue Earth and Nicollet County Humane Society to put together a plan for their new facility. On Arbor Day 2007, we donated $5,000 for new trees in St. Peter, Mankato and North Mankato, and donated our staff time to assist in the planting. This particular type of pro-bono work also demonstrated our commitment to sustainability and going green.

How does it make you feel when you drive around southern Minnesota and see “your” buildings? In a way, they are your babies. You helped nurture their growth. Your signature is all over southern Minnesota.

What I’ve really begun to appreciate is how we can change a neighborhood or community and make it a better place to live, play or work. That’s what I really believe is important about architecture. I hope we have enhanced communities and made them better places. I’ve actually had people come up and thank me for introducing good design into Southern Minnesota and for being willing to think outside-the-box more than what had been done in the past.

People coming from out of state to interview for a job in this region will take back memories of different communities. Good design, at enough buildings, would leave a lasting impression. Don’t you think?

I would hope so. A community’s architecture reflects its character. Right or wrong, people respond positively or negatively to the architecture. We hope we have demonstrated the positive impact architecture can have on a community. We hope people want to come here to work and live and realize this is a progressive community willing to embrace bold design.

Someone knowing you well told me you never get flustered. You have this calm, cool, collected personality. In part, has that calm demeanor contributed to your success?

I guess that is true. I was just born that way. I am very calm. And I have to be because I have a lot of high-energy people around me, including clients, designers and staff. There does have to be a level of calmness here, otherwise everything could just explode. This profession can be very stressful with lots of details and coordination having to be handled by the architects. I try to rationally analyze every situation. I believe there is always a solution to any problem. Calmness tends to help people think more rationally. I am pretty steady and my staff thanks me for it. If encountering a problem, an employee knows they can come to me to discuss it and they don’t have to fear me. Contractors also feel comfortable coming to me to discuss issues and solutions. I’ve learned we all make mistakes, and if one is made, we all need to work together to find the solution.

What Is Green Design?

PAULSEN: That’s a broad term. Green to us is being smart about how we use building materials, preserve the land and the site, reduce water usage, minimize energy consumption, and how we improve indoor environmental quality. As a firm we have made a strong commitment to study and promote green design principles. Our firm is a LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certified firm. We have several LEED Accredited Professionals on staff, which is the highest level of sustainable expertise recognized in the industry. We try to incorporate sustainable strategies into all our building designs now and have put in place a process our designers use to help educate our clients about the benefits of green design. We were on the forefront of promoting green design as a strategy several years before it became a hot topic. Being ahead of the industry trends fits our ‘bold design’ mission well. I’m proud we have already designed or are designing five sustainable or LEED certified projects, the largest being the new Blue Earth County Justice Center, which will be LEED certified at the silver level. The Justice Center will also be the first LEED certified building in Southern Minnesota.

Different sustainable strategies have different costs, and those costs typically range anywhere from zero to 20 percent of additional construction cost. Often, a businessperson’s first question regarding sustainable design: What’s the payback? We usually study and then try to incorporate sustainable strategies having a five- to seven-year payback for clients. Some paybacks are instantaneous, such as the $150 occupancy sensor paying for itself in terms of lower heating and electricity costs. The payback to our firm of deciding to focus on green design: We want to be leaders in that sector. When you are a leader people come to you. Clients want to work with people who are the best at what they do.

Getting to know you: Bryan Paulsen

Family: Wife, Tami Paulsen; son, Jonny.

Born: March 18, 1956.

Education: Mankato East 1974; University of Minnesota School of Architecture 1982.