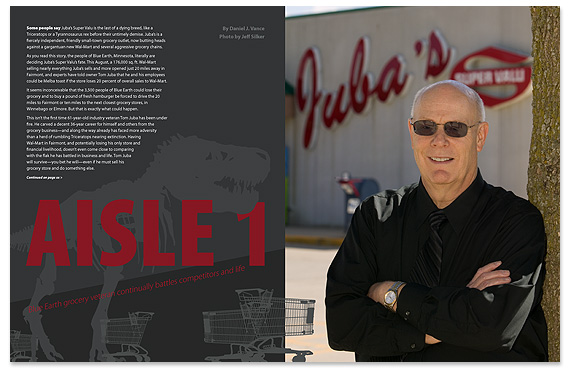

Juba’s Super Valu

Blue Earth grocery veteran continually battles competitors and life

Photo By Jeff Silker

Some people say Juba’s Super Valu is the last of a dying breed, like a Triceratops or a Tyrannosaurus rex before their untimely demise. Juba’s is a fiercely independent, friendly small-town grocery outlet, now butting heads against a gargantuan new Wal-Mart and several aggressive grocery chains.

As you read this story, the people of Blue Earth, Minnesota, literally are deciding Juba’s Super Valu’s fate. This August, a 176,000 sq. ft. Wal-Mart selling nearly everything Juba’s sells and more opened just 20 miles away in Fairmont, and experts have told owner Tom Juba that he and his employees could be Melba toast if the store loses 20 percent of overall sales to Wal-Mart.

It seems inconceivable that the 3,500 people of Blue Earth could lose their grocery and to buy a pound of fresh hamburger be forced to drive the 20 miles to Fairmont or ten miles to the next closest grocery stores, in Winnebago or Elmore. But that is exactly what could happen.

This isn’t the first time 61-year-old industry veteran Tom Juba has been under fire. He carved a decent 36-year career for himself and others from the grocery business—and along the way already has faced more adversity than a herd of rumbling Triceratops nearing extinction. Having Wal-Mart in Fairmont, and potentially losing his only store and financial livelihood, doesn’t even come close to comparing with the flak he has battled in business and life. Tom Juba will survive—you bet he will—even if he must sell his grocery store and do something else.

“I grew up early in life in Pipestone,” said Tom Juba from a quiet spot in Hamilton Hall, the 400-seat Blue Earth banquet facility that he owns connected to Juba’s Super Valu. “My dad Lambert, who people called ‘Buck,’ started with Super Valu in 1946.”

Buck Juba, who is age 85 today, bought into a pocket-sized, downtown Marshall grocery store in the early 1940s along with his brother-in-law. Not long after that purchase, Buck was drafted into the Army Air Corps and wouldn’t return until early 1945. Tom was born that November. Buck and his brother-in-law split when the latter wanted out, and so Buck took his half of the money to open a grocery in Pipestone.

“When building materials finally became available in 1951, he built a new store in Pipestone of about 8,000 sq. ft.,” said Juba. From a young age, and right alongside dad, Tom Juba was bagging potatoes, slicing meat, and learning how to “candle” eggs. There were no child labor laws affecting children of a business owner. In 1956, Buck aggressively expanded to two stores by building a spacious-for-the-day 20,000 sq. ft. location in Willmar and sent what he thought was his best employee to manage it. Buck even helped the manager buy a house. “That manager turned out to be not such a good employee when on his own,” said Juba. “He was dishonest, and didn’t treat customers well.”

Within two years, that store was failing, and Buck Juba realized he would have to move to Willmar to save the store by managing it himself. The Willmar location cost a considerable sum. The sudden move came when Tom, the oldest of five Juba children, was entering the seventh grade. He helped out all through high school. In 1964, six years later, he graduated from Willmar High and went on to Western Michigan University to major in supermarket management. His short-term goal was to more fully learn the grocery business before returning to manage the Pipestone store. Uncle Sam had other ideas.

Said Juba, “I graduated from Western Michigan University in 1968 and three days later was drafted into the Army. My full intent had been to go back home and manage Pipestone. I got a practical education in the Army. Because of my grocery background, I became an Army meat inspector.”

He attended schools in Chicago to learn food and meat inspecting and was sent to Denison, Iowa, only four hours from home. The meat plant there was one of only six in the nation processing boneless beef for military contracts. Juba’s workday ranged from five in the morning to seven at night, and he inspected a 400-head-a-day kill. He learned that carcass beef was almost 60 percent waste, and that the Army wasn’t too keen on shipping the waste, including bones, all over the world. The Denison plant processed and then packaged beef into 80-pound boxes for freezing and shipment. Boneless beef wouldn’t hit retail supermarkets until 1973, but when it did, Juba would be ready.

By Juba’s discharge in 1971, Juba’s Super Valu locations in Pipestone and Willmar were prospering. Looking to expand to three stores, Buck helped Tom secure a Small Business Administration loan to buy a successful supermarket in Blue Earth from Elmer Knudsen. Two years later Buck helped Tom’s brother, also an Army food inspector, purchase a fourth store in Shakopee.

“Eventually we also bought a fifth store in Spicer,” said Juba, “and then a convenience store between Willmar and Spicer called E-Z Mart. It had a Standard Oil franchise, which did tons of business in the summer.” The Jubas and their locations were thriving.

All seemed well for the clan—and the outlook bright—until misfortune began striking like a fistful of hot matches, first in 1975. “Our Willmar store burned down that year and we had to rebuild,” said Juba. “We were concerned about our employees, and their lives, so we bought another store for the one-year interim, on the west side of Willmar. In the meantime, a large chain came to town. We had been the number one store in Willmar, but lost our position because of the fire.”

The Jubas lived in Blue Earth from 1971-77, then moved to Willmar when Buck felt that location needed a “Juba” after the fire. Tom and his family would live in Willmar until 1990, about two years after selling that location. Said Juba, “I was supervising the other stores by that time. It seemed kind of stupid to be living in Willmar as a supervisor and not having a store there.” So they packed up and returned to Blue Earth.

Their E-Z Mart convenience store on Eagle Lake had been the first to go, prior to Willmar. It prospered well in summer months but carried razor-thin margins most winters. The Jubas tried changing supplier affiliations and the name before selling out. They experienced firsthand the difficulty trying to make a profit selling a commodity, gasoline.

In 1990, they sold their Spicer grocery after finding a local buyer. Again, it had prospered in the summer months, but not quite enough the rest of the year.

In 1993, the Jubas, down to three stores, took their biggest gamble yet by converting their Shakopee location into a 38,000 sq. ft. County Market. It had mud flaps and whistles and made the Jubas feel proud. The night before the store’s grand opening, Tom’s brother Dick slipped off a cooler while trying to trace a computer cable and plummeted seventeen feet through a suspended ceiling. Landing hard, he crushed his heel, broke his back, cut his head, and “darn near killed himself,” said Juba. Dick, the Shakopee store manager, went through physical therapy for nearly two years. Tom spent two or three days a week in Shakopee for two years. When it became apparent that Dick wasn’t physically able to manage the store, the Jubas sold that location to Rademacher’s of Prior Lake.

Tom’s other brother Mike, the youngest of the three Juba brothers, developed a bad back working in Pipestone as the assistant manager. He left the family business to become a computer guru for Super Valu at its Eden Prairie home office, where he worked until he became permanently disabled in 2005.

By 2005, due to Mike and Dick’s health issues, Tom, by default, was the sole Juba brother left in the family business. To insure that his Pipestone store would remain competitive, Juba, at age 59, suddenly was facing a projected expenditure of several million dollars. So he sold that location to Coburn’s of St. Cloud.

Today, the once-growing Juba’s Super Valu group of six is down to one Blue Earth grocery. Tom’s 33-year-old son Tim manages that store, which grosses between five and ten million dollars a year. He has been chomping at the bit to carry on the family tradition of owning and managing a grocery store.

It’s not as if Tom Juba hasn’t tried everything to build his business. He owns a 400-seat banquet hall, Hamilton’s, that hosts about 35 weddings annually, local Kiwanis, Lions, Sertoma and Blue Earth Area school foundation fundraisers, trade shows, and the every-two-year Faribault County salute to state politicians. It is connected to his grocery store. The banquet business helps his supermarket sales. A restaurant site connected to the banquet hall, formerly Hamilton’s Restaurant, has been vacant for almost a year and a half. It’s not that the restaurant didn’t do enough business to make a profit, said Juba, but for the most part it didn’t have the right people managing. Finally, the Jubas just gave up in frustration. He said he was “open” to the right person purchasing the restaurant and leasing the space from him.

Several years ago Juba launched what became a highly successful summer-only hamburger stand on his parking lot, often seen with a long line of people queuing for lunches. He also opened a year-round lunch spot on the east side of Blue Earth inside the agriculture center owned by Neil Eckles. They help make up for lost restaurant sales.

As for advertising, he buys daily airtime on local radio station KBEW to announce another “KBEW Radio Special of the Day,” in which customers have a limited time to rush in and buy daily meat bargains. “A chain store doesn’t have daily advertising on a local radio station,” said Juba, noting a competitive advantage. He cited superior service and perishables quality as other leg-ups over Wal-Mart.

To increase summer traffic flow, Juba’s Super Valu sponsors a farmer’s market in its parking lot Saturday mornings and Tuesday afternoons. Local growers sell produce for only a $2 charge. And Wednesdays are a huge draw: Senior Citizen’s Day, in which elderly customers receive five percent off the top on everything. “We also try to help our community and we’re involved financially helping many groups,” said Juba while noting that local goodwill goes only so far.

Blue Earth already has a 40,000 sq. ft. Wal-Mart. After opening twenty years ago, that store especially began hurting Juba’s sales of household and paper goods, such as laundry detergent, plastic bags, toilet paper and diapers.

Grocery experts have told Juba that the new Fairmont Wal-Mart, which includes a rather large grocery store, could diminish his overall sales 20 percent. If that happens, “We won’t make it,” he said without hesitation. And, if that happens, the 3,500 people of Blue Earth will be traveling about seven miles to either Winnebago or Elmore, or 20 miles to Fairmont, to buy a pound of fresh hamburger.

All considered, Juba the last few years has had more than Wal-Mart occupying his mind. In 2004, Juba’s wife Sue learned she had a rare form of cancer that started in her sinus and aggressively attacked her jaw. Mayo Clinic experts said that fewer than a thousand Americans have been identified having it. Sixteen surgeons worked overtime to amputate a portion of Sue’s face, including part of her jaw and an eye socket. Her weight dropped precipitously to 83 pounds.

“She is fortunate to be alive,” said Juba, also noting her 36 radiation treatments. “I was pretty much worthless (as far as work goes) those first six months following the operation. A year later the cancer reappeared on the roof of her mouth. You have to get five years out before they consider a person cancer-free. You just do what you have to do to get through. I’m a very optimistic person. Sue and I are closer now than we have ever been. Going through it gave me a whole different outlook on life.”

Now facing Wal-Mart head-on, and the possibility of selling out, Juba seems to have a fighter’s instinct to do everything humanly possible to save his business, career and life. Unlike some naysayers, he doesn’t see himself as the dying dinosaur, the Triceratops or Tyrannosaurus rex. Tom Juba sincerely desires his son Tim to continue the longstanding family tradition in an industry that has meant so much. Yet, at the same time, his wife means much more.

1950s JUBA’S

“My dad worked really long and hard hours. He helped unload trucks by sliding cases by hand down a slick board into the store’s basement. I remember he bought hundreds of cases at a time of Miracle Whip and Velveeta from Kraft Foods. To this day I don’t think anyone has ever made a nickel on those products. You always sold them at or near cost because they were competitive items. Back then you had to have 15,000 pounds to get a direct truck from Kraft and those were heavy items.” —Tom Juba, owner.

JOLLY GREEN

According to the State of Minnesota, the city of Blue Earth has a higher than average concentration of elderly people. That tends to work in Juba’s Super Valu’s favor because older customers tend to be more loyal, meaning they won’t be as likely to switch to Wal-Mart. But the demographics work against Juba’s when the store is trying to sell higher-margin, new items, including those geared for children. The Super Valu warehouse in Hopkins automatically sends Juba’s a case of every new product, often with a deep discount to entice Juba to buy more. He would very much like to buy more, but many of his customers tend to be loyal to established national brands, such as Campbell’s, Charmin, Betty Crocker, Kellogg’s, Heinz, and Kraft.

In particular, the residents of Blue Earth have developed a loyalty towards a big green man. “This is a Green Giant town,” said Juba. “Everybody I know in Blue Earth either used to work there or their mom or dad did. Anything Green Giant comes out with sells well here. This week we have Green Giant Idaho Russet Potatoes and Green Giant Fresh Mushrooms in our ad. Our store sells way more than other stores of those products just because of the name.”

LOST SALESMEN

Just 20 years ago, Tom Juba would meet daily with as many as five or six salespeople in his Blue Earth grocery office. Today, to reduce costs, manufacturers have stopped sending salespeople to most grocery stores. Juba has few face-to-face interactions anymore. Salespeople deal with him via email, telephone, and fax.

“Most of my interactions are done that way,” Juba said. “Sometimes salespeople even email us deals six months in advance.”

When visiting, salesmen used to write Juba checks or credit memos to cover damaged product. Today, because salesmen no longer visit, Super Valu must keep track of Juba’s purchases of various products before sending him a credit of .003 percent to cover shrink and damage. Most damaged product is returned to Super Valu and donated to food bank operations.

Juba also used to count on salespeople to regularly reset sections of his store, such as the breakfast cereal or baking sections, in order to “cut in” new products and ferret out discontinued items. Today, with salespeople physically absent, Juba must pay a $3,600 annual fee to a shelf management service that does the necessary weekly work.

WHAT SELLS

Pampers: “When they came out in the late ‘60s, all of a sudden you had to have a four-foot section just for Pampers. And where would we find four feet? Pampers sales took off, and the section then grew to 24 feet. Now they have compacted the diapers, and the section has shrunk back down. There have been other new categories over the years that we have had to create space for, including trash bags, yogurt, granola bars, shelf-stable dinners, and bottled water.”

Cake Mix: “We used to have a whole complete aisle of cake mix, except for the bottom two shelves, which included sugar and flour.”

Frozen Juice: “That used to be a huge seller, and now people don’t have time to mix three cans of water with it, so they buy it from the dairy case.”

Organic Milk: “We just began selling organic milk for the first time this week. It doesn’t seem to sell here. We used to have an end cap of just organic and it didn’t fly.”

Generic Food: “That used to be popular in the 1980s. People got tired of the inconsistent quality, I think. We have only one generic item remaining: generic potato chips. They fry them in inexpensive oil and put a lot more salt on them to cover up the taste. Some people prefer them.”

online cbd gummies

purchase soma online

purchase CBD gummies for sale

cbd gummies reviews

purchase cbd online shop

purchase cbd gummies near me

purchase tramadol

purchase xanax online

purchase soma on line

purchase soma online

purchase tramadol on line

purchase soma online

purchase tramadol

tramadol buy online

Cigarettes: “We lost that business a long time ago. Serious smokers go to casinos because cigarettes aren’t taxed by the state there. We still sell single packs, but not cartons. Our cigarette business is ten percent of what it was. I debated not selling the darned things because I don’t like them. But in Minnesota 20 percent of adults still smoke. You can’t ignore them.”

© 2007 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

jubas of blue earth is killing me with their SUPERHIGH prices. I cant drive out of town, or to the other side of town to get my groceries. i am stuck with

Juba’s maybe a last of a dying breed, but their prices and the monopoly they have in blue earth is making it hard for me to support them. I get all my meat at the blue earth meat locker now days and driving to fairmont Walmart is fine by me than paying the highway robbery prices of juba’s.

Well I love Juba’s. I go there about every day to shop and I love how our small town can have such a famous store and its so useful too, now with the Gas Station, I would like to see the look on Buck’s face when he saw his son and grand-son, in the makings of the store, I bet he is so proud. Walmart isnt as god at all, people are so friendly work at jubas and all friends in high school whork together.

High prices ? You obviously don’t really shop there, I just picked up 4 Tombstone pizzas for $10, is that expensive ? It is a business in a small community, they are not a Big Name store, so they can’t offer cheap pricing on everything . Believe me, I have done a lot on comparisons in the area and have found Juba’s to be cheaper or close to on many items. And the Meat and Produce depts. are way freshier than any other in the area, I guess paying a little more for quality is a better deal than driving out of town !