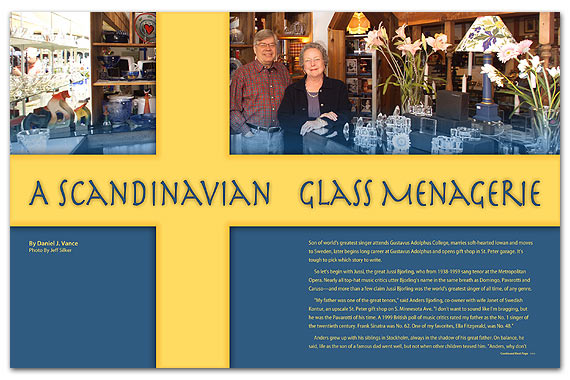

Swedish Kontur

Photo by Jeff Silker

Son of world’s greatest singer attends Gustavus Adolphus College, marries soft-hearted Iowan and moves to Sweden, later begins long career at Gustavus Adolphus and opens gift shop in St. Peter garage. It’s tough to pick which story to write.

So let’s begin with Jussi, the great Jussi Bjorling, who from 1938-1959 sang tenor at the Metropolitan Opera. Nearly all top-hat music critics utter Bjorling’s name in the same breath as Domingo, Pavarotti and Caruso—and more than a few claim Jussi Bjorling was the world’s greatest singer of all time, of any genre.

“My father was one of the great tenors,” said Anders Bjorling, co-owner with wife Janet of Swedish Kontur, an upscale St. Peter gift shop on S. Minnesota Ave. “I don’t want to sound like I’m bragging, but he was the Pavarotti of his time. A 1999 British poll of music critics rated my father as the No. 1 singer of the twentieth century. Frank Sinatra was No. 62. One of my favorites, Ella Fitzgerald, was No. 48.”

Anders grew up with his siblings in Stockholm, always in the shadow of his great father. On balance, he said, life as the son of a famous dad went well, but not when other children teased him. “Anders, why don’t you sing a little?” they would say. Rather than a great voice, Anders inherited a talent for numbers.

His mom and dad often were away from home, globetrotting from one great opera house to the next. Fortunately, Anders had in-house playmates to carry him through Swedish winters: a brother and sister. “There were long periods when my mom and dad weren’t home,” he said. “My maternal grandmother took care of us. Without her I don’t know how things would have worked out.”

After completing the equivalent of junior college and his Swedish military obligation, he met up with an old friend who’d spent a year in America as an exchange student. “He told me how wonderful his exchange experience was,” said Anders, “and he said that I had to try it. He had been a ‘mother’s boy’ before, but in returning to Sweden he was a man of the world. His experience seemed appealing. Going to America would be a way for me to be on my own.” So in 1956 at age 20 he packed his belongings and left family and friends for Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minn.

It was at Gustavus Adolphus College, with its tree-filled college campus overlooking St. Peter and the Minnesota River valley, where he met the softhearted Iowan. On one of their first dates, Janet asked him, “What does your father do for a living?”

Anders answered, “He sings.”

“What does he sing?”

“Oh, opera, things like that.”

He didn’t make much of it. That night Janet was talking with her roommate, a music major, and began to wonder. She said, “You know the Swedish boy I’ve been dating? He says his father is an opera singer.”

The roommate looked up from a book. “Oh, who?”

“Jussi Bjorling.”

“Jussi Bjorling! You’ve got to be kidding!”

Janet and Anders graduated in May 1958, married within a month, and were off to Sweden for four years. “I did know how to speak a little Swedish,” said Janet, today the co-owner of Swedish Kontur and former manager. “When I knew after being engaged that we would be moving to Sweden, I took Swedish classes at Gustavus Adolphus. However, what I learned and what I actually had to speak weren’t the same. At parties in Sweden, people started in English, but as the party went on they spoke Swedish. I knew I was going to have to learn more, especially since Anders’ grandmother, whom I loved very much, couldn’t speak English.” Apparently Janet’s pronunciation was excellent because everyone thought she was Swedish; yet because of her limited vocabulary they also thought she was “kind of dumb,” she said.

The cultural shift from farm-belt Waterloo, Iowa, to Stockholm, Sweden, surprisingly, did not faze her. However, the Swedes were a “shy” and “reticent” people. “If you didn’t understand that shyness was part of their culture you would think they were cold,” she said. She liked the sincere way Swedes handled people. They weren’t ones to spontaneously invite people over and then be surprised when the guests came. When guests were expected, they made sure their house was clean, the food right, and everything, perfect.

And she was in Sweden as the daughter-in-law of the great Jussi Bjorling. Her first exposure to opera had been as a freshman at Wartburg College before transferring to Gustavus Adolphus. In 1957 when she and Anders were engaged, Jussi invited them to a performance because he wanted firsthand to meet this “American girl” his son would marry. In New York, he opened with a rousing aria. “People just shouted and carried on,” she said. “I thought he must be something! I had never anywhere seen an audience react that way. The more he sang the louder they clapped and screamed. At the end of his performance he said to the audience, ‘Because you have been so nice to me, I would like to sing ‘Because’ for you.’”

At that precise moment Anders’ mother turned, Janet said, and she said in a thick, singsong Swedish accent, “How cor-ny can you get!” Janet said the experience overwhelmed her; she had neither seen nor heard anything like it.

The long career at Gustavus Adolphus began in 1962. “We had planned all along on returning to America,” said Anders. “When we got here I was putting in applications at different companies when one of my former professors heard I was looking.” He received a job offer from the Gustavus Adolphus finance office. He would work there seven years before being named Director of Data Processing, a field far removed from his father’s opera career. When he retired in 1998 he was the Gusties’ Controller.

“Going back to America had to do with striking out on my own,” he said.

It’s not that he disliked Sweden, now one of the most Americanized of European countries. “But the main difference between the two cultures is that Swedes take life more seriously than Americans,” he said. “We’re more relaxed and casual. They can be very serious,” he laughs. Sweden and all the Scandinavian countries have a high standard of living, he says, even higher than the United States.

And finally, that brings us to the gift shop opened in a St. Peter garage. The year was 1962 and the Bjorlings yet in Sweden knew they would need extra cash for starting a family business in southern Minnesota. While a Gustavus Adolphus student, Bjorling had been disappointed in not being able to find high-quality Swedish gifts to buy, such as glass, silver and handicrafts. Before they left Sweden, they established an account with a small glass manufacturer, placed an order, and in America made contacts with a Swedish silversmith and textile artist. Family and friends thought their quaint idea of a little St. Peter gift shop was doomed to fail.

One contact made in America was Orrefors, the leading Swedish glass (or crystal) manufacturer. Its sales representative lived in Chicago, and drove out to St. Peter to look into this possible new account. “When he drove up, we were remodeling our garage into a shop,” Anders said. “We had lumber all over. I’m sure he wondered what we were doing, thinking we could sell Orrefors from a garage. We eventually convinced him to set us up as a new account, but it took all afternoon. I don’t know how we did that.”

They worked hard to spread the Swedish glass gospel. They spoke to any service organization that would listen. Janet opened up shop every afternoon from 1-5. But still not much luck, that is, until they received a break that would confirm a dream and make their lifetime.

To make their little store look attractive, the Bjorlings had ordered five outstanding “show” pieces of crystal that cost around $100 each. A physician from Mankato Clinic walked in one day. He’d had a recent operation, and wanted to show his appreciation for a job well done by buying five of his medical colleagues something special. He purchased all five showpieces.

Janet said, “I remember him saying, ‘I want this piece, this piece, this piece.’ I was trying to be really calm. Then he wanted them gift-wrapped. I was so nervous, thinking I might drop one. Up until then we had wondered if we were ever going to make anything of the business. When he left I telephoned Anders. We’ll never forget what the physician did. It was one of the exciting times in our store.”

As business grew—helped by word of mouth from wives of Mankato Clinic doctors and other customers—the Bjorlings realized they needed more space. In 1967 they rented a storefront in downtown St. Peter. In 1972 they purchased the Faust Drug building across Minnesota Avenue, and “inherited” Lila Faust as an employee. “That was the best part of the deal,” said Janet. “Lila has been wonderful.”

Today, Swedish Kontur is in transition. Kathy Gostonczik began managing the shop two years ago when Janet, 68, experienced health problems. Anders, 67, works 15-20 hours a week yet, orders merchandise and figures the numbers, his strong suits, and occasionally works the cash register during peak periods. Excellent part-time employees round out the workforce.

Business spikes during Gustavus Adolphus events, like Christmas in Christ Chapel, the Nobel Conference, and Honor’s and Parent’s Day. In the 1960s, most customers were Scandinavian, but that no longer holds true. About 40 percent of annual sales are from glass, including big names Orrefors and Kosta-Boda of Sweden, and Iittala of Finland. Glass pieces range in cost from $10 votive candleholders to $500 showpieces. Norwegian sweaters and Scandinavian Christmas ornaments sell well before Christmas, and Swedish clogs, which were a huge sales item in the 1960s, yet hold their own. “The clogs still sell,” said Anders, “but not the way they used to. In the late 1960s once we sold 52 pair in one day. It was a big fad, and not just with students. They were unusual, and good for your feet. Now they are making a comeback.”

Other items for sale include Scandinavian candies, cookies and jams, which account for 10 percent of sales, and silver jewelry from Sweden, another 10 percent. About 50 percent of their business comes in mid-October through January 1, with December turning Swedish Kontur into a “mad house.”

One new business direction has been corporate sales. A large medical device company recently purchased 300 pieces of Kosta-Boda crystal as gifts for doctors and healthcare workers taking part in a clinical trial.

Now in semi-retirement, the Bjorlings visit Sweden annually on trips that are becoming less and less business oriented. They still visit glass companies such as Orrefors to buy new product, and search for Swedish jewelry not sold in America. But they also see relatives. Anders’ father Jussi died in 1960, but his mother at 93 is still living in Stockholm. She played a key role in funding Gustavus Adolphus’ Bjorling Concert Hall.

As for full retirement and the potential sale of their business, the Bjorlings are “at the point now where we need to think about that,” said Anders. “One way or another this store will continue, either with the family or with an outside owner.”

Janet added, “We’ve had wonderful people working here through the years. The current group works well together. We had our best Christmas season ever, which shows you I don’t necessarily have to be here for that to happen.”

Shutter Bug Mania

In his semi-retirement Anders finally has time for his photography, a lifelong passion that has become his main avocation. He and two others in December displayed photographs at the local community center. He felt intimidated. “I’d never done that before, all of a sudden showing my photographic ‘babies’ in public.”

Since then his photography has been displayed at the Interpretive Center in the Arboretum at Gustavus Adolphus, and in August displayed at the American-Swedish Institute in Minneapolis. For subjects he prefers landscapes, people and flowers, with the occasional unusual window or door striking his fancy.

“For landscapes I’m always looking for that sunset I’ve never seen,” he shared. “In people I look for interesting faces. We were in Nepal four years ago. Everywhere you turned, there were interesting people or situations to photograph. In America I love New Mexico and Arizona, which is where we were on September 11, 2001, riding horses down into a canyon.”

“Look Who Walked In.”

“John Denver came in the store once with his two small children,” said Anders Bjorling of a spring day in the 1970s. “They were buying a Mother’s Day gift, and picked out a wonderful piece of Orrefors. I remember how he sat with his kids on the shop floor, and they wrote the card together.”

Other guests left memories not-so-fond. “Last year Jesse Ventura stopped in,” said Anders. “He was in the shop, but wasn’t a customer. One lady in the shop questioned him about education funding. He said he wanted school systems to be accountable. He certainly is a big fellow.”

The Swedish Kontur guest book has names of people from dozens of foreign countries and nearly every state. The gift shop is a popular place for St. Peter residents to bring out-of-town friends.

No Place Like Home

Like everyone in St. Peter, the Bjorlings have a tornado story.

They heard the news while with Gustavus Adolphus staff at a conference in Arizona on March 28, 1998. A newscaster said downtown St. Peter was totally destroyed, the college devastated, and homes lost. “We were trying to think what would be worse, losing the home or the business,” said Janet Bjorling. “We decided the home.”

Their home was livable. Wood from the college gym had crashed through their bedroom window. And Swedish Kontur? One show window shattered. Everything on that side of the store had to be replaced. But none of the crystal on the other side of the room, and in the middle, broke. Janet said, “We had a skylight in the apartment above, and it didn’t break, and yet stores a couple doors down had terrible damage. We just missed it.”

At the time of the tornado Anders was weeks away from retirement and a well-deserved vacation in Scotland and Ireland. He stayed on until June to help Gustavus Adolphus with the recovery.

© 2003 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.