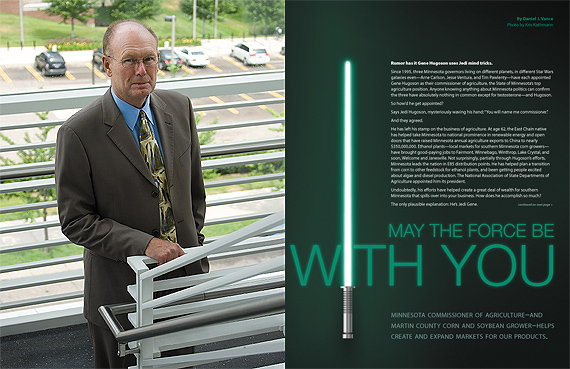

Gene Hugoson

MINNESOTA COMMISSIONER OF AGRICULTURE–AND MARTIN COUNTY CORN AND SOYBEAN GROWER–HELPS CREATE AND EXPAND MARKETS FOR OUR PRODUCTS.

Photo by Kris Kathmann

Rumor has it Gene Hugoson uses Jedi mind tricks.

Since 1995, three Minnesota governors living on different planets, in different Star Wars galaxies even—Arne Carlson, Jesse Ventura, and Tim Pawlenty—have each appointed Gene Hugoson as their commissioner of agriculture, the State of Minnesota’s top agriculture position. Anyone knowing anything about Minnesota politics can confirm the three have absolutely nothing in common except for testosterone—and Hugoson.

So how’d he get appointed?

Says Jedi Hugoson, mysteriously waving his hand: “You will name me commissioner.”

And they agreed.

He has left his stamp on the business of agriculture. At age 62, the East Chain native has helped take Minnesota to national prominence in renewable energy and open doors that have raised Minnesota annual agriculture exports to China to nearly $350,000,000. Ethanol plants—local markets for southern Minnesota corn growers—have brought good-paying jobs to Fairmont, Winnebago, Winthrop, Lake Crystal, and soon, Welcome and Janesville. Not surprisingly, partially through Hugoson’s efforts, Minnesota leads the nation in E85 distribution points. He has helped plan a transition from corn to other feedstock for ethanol plants, and been getting people excited about algae and diesel production. The National Association of State Departments of Agriculture appointed him its president.

Undoubtedly, his efforts have helped create a great deal of wealth for southern Minnesota that spills over into your business. How does he accomplish so much?

The only plausible explanation: He’s Jedi Gene.

Tell us your personal story.

I grew up on a fourth-generation farm in East Chain, Minnesota, and moved off the family farm later. My brother lives there now. I went to school in East Chain and graduated with a whopping class size of eighteen, all farm kids. K-12 was all in one building. Everyone knew everyone.

I would imagine with a class of eighteen, all the students had to work together to get anything done.

We did. Everybody was involved in everything in terms of extracurricular activities, because if you weren’t involved, there wouldn’t be extracurricular activities for others to participate in. It was not unusual for kids to play three seasonal sports, and be in band, and choir, and everything else to keep those activities going, too. What we lacked in academic opportunity, we gained in extracurricular knowledge and experience.

So being small had its benefits.

The people of our community—descendants of Scandinavian and Polish immigrants—had (and have) a strong work ethic. We were close knit. Going on a vacation then was considered a luxury. People worked long hours, especially if you milked cows. The summer activities for most kids involved baling hay and walking the beans. Interestingly, we have a class reunion coming up in a few weeks—I hate to say which one.

East Chain was isolated from the world. Our class trip was only to Chicago, and for some kids that trip was the first time they had been out of state, except for Iowa, only four miles away. Besides East Chain High, I went to Augsburg College in Minneapolis for four years to earn a bachelor’s degree with a social sciences teaching major.

When Gov. Pawlenty re-appointed you in 2002, he said, “Minnesota needs a commissioner of agriculture who has dirt under his fingernails, and who understands the need to find new uses and markets for Minnesota’s crops.” You’ve already talked about the “dirt” under your fingernails. Tell us what you understand about the need to find new uses and markets for our crops.

My whole time as commissioner I’ve held two jobs. I still farm. I somewhat jokingly say I farm because the last two governors I’ve worked for said they were only going to hire a farmer as their commissioner. The reality is if I don’t keep on farming, I won’t get to keep my day job.

I farm 660 acres. By today’s standards that’s a small- to medium-sized operation. I go home on weekends. My wife has maintained our residence in Martin County because, up until last year, she taught school in Truman. It didn’t work for her to be up here. So I commute back and forth on weekends.

In all my time in public service, there has been what I would describe as a struggle going on in the farm economy. I started out in the legislature in 1987 in the throes of a farm crisis. The whole issue, at that point, was how to establish farming as a viable occupation. People had issues keeping their farms. One problem then: In any business, a balance must exist between production and consumption. It doesn’t pay to produce widgets, for example, unless a market exists for them. If a market exists for 100 widgets, and you’re producing 200, then you have a problem. In the 1980s, we were producing far more than we were consuming.

One alternative was to find ways for people to increase their eating, but most of us were eating far too much anyway. In reality, we had to find other uses for our agricultural products. The key, of course, was to develop products that had markets. When I came into the legislature, renewable fuels were beginning to be talked about along with the idea of developing overseas markets.

The United States had (and has) only five percent of the world’s population. There was a huge market outside our borders. But American agriculture didn’t become serious enough about international trade until it was too late. Now we are playing on a highly competitive field. For a long time, American agriculture dominated the international scene. That’s no longer the case. We are up against some very well financed and technologically advanced countries.

Before being appointed commissioner of agriculture in 1995, you were elected to five terms in the Minnesota House. Four of those years you were assistant minority leader. In that last role, what leadership skills did you learn that have helped you in your role today?

I learned to work with my peers. As assistant minority leader, I was in a unique position in that I didn’t have authority over other members. I had to find ways to get people to work together for common goals, and that fits my personal approach. I have never seen myself as a dictator. I prefer to manage by utilizing people’s skills. As commissioner of agriculture, I hire good people, let them do their jobs, and get out of their way. One person can’t do everything.

You’ve taken graduate level courses in history at Minnesota State. Did you learn something there that gives you insight into situations on your job today?

First, a couple of things. Certainly, my time in Vietnam shaped me. It gave me an introduction to the Asian culture, people and area. I was in Vietnam from 1969-70, and was at MSU from 1971-74.

The United States has been around for only a couple hundred years. China, for instance, can trace back its roots thousands of years. In history class, one thing that became obvious to me about China was that its people over time had been sophisticated marketers. Back in the 1960s, most Americans knew Asia had communist-dominated governments. Yet its people have always been entrepreneurial. The communist domination of Asia was just a blip in the history of an entrepreneurial people.

Look how rapidly the Chinese economy has exploded since its government gave its people entrepreneurial opportunities. Look at what they have done. They had to decide whether to put their focus on manufacturing or agriculture. They came to the conclusion they couldn’t do both. So they chose manufacturing and used those profits to import food. That has turned out to be advantageous for Minnesota farmers. In 2007, Minnesota exported about $350,000,000 worth of agricultural products to China. That country is our third-largest export market, above Canada.

As commissioner of agriculture, I accompanied Gov. Carlson to China the first time, and I traveled there again with Gov. Ventura and Gov. Pawlenty. Each of my seven or eight times in China I have seen changes in their country, including last year.

Often I’ll hear a politician returning from an overseas trade mission say it was “successful.” What makes a trade mission successful?

American business relationships tend to be impersonal. We buy and sell over the Internet and think nothing of it. In Asia, and in some European countries, so much of how they do business is to establish personal relationships first.

Trust?

Trust—and building onto that a networking system that ultimately leads to actual negotiations and sales. In addition—and I don’t mean this the way it might sound—but Asian countries, in particular, place greater significance on government officials than we do in this country. Most American businesspeople think of government officials as obstacles. In Asia, government officials are keys to opening doors. It’s their protocol. When our governor goes on a trade mission, people pay attention—not only from our side, but theirs as well. Also, we have to work at maintaining our relationships there. You always run the risk of losing them. Right now, we have an economic advantage because of the cheap dollar.

Could you give an example of a relationship you’ve established?

I’ll give two. We have worked hard in renewable fuels, and Gov. Pawlenty has said we intend on staying in a No. 1 position nationally—and not just with corn and soybeans, but also with other renewable fuels such as biomass and cellulose materials.

The Chinese are interested in renewable fuels. As a result, when over in Beijing a while ago, Gov. Pawlenty addressed a biofuels conference. The conference didn’t get much publicity, but it was the beginning of a relationship with a research facility at a Chinese university. The relationship is still going. As a result, we’ve had a tremendous flow of Chinese to Minnesota, an average of fifteen delegations annually. In part, they are learning about renewable fuels.

The other relationship is with the province of Szechuan. We began a dialog with them on one of my early visits. The relationship developed to the point where we had two young men come from their ministry of agriculture to spend two years in Minnesota. They were married and had left their families behind. They spent half their time at the University of Minnesota and half job-shadowing me at the Department of Agriculture.

It’s a two-way relationship then.

More Chinese come here than Minnesotans go there. That relationship gives us opportunities. When coming here, they visit places they might end up doing business with. They like seeing where their product comes from. They would much rather feel like they’re buying from farmers than Cargill, for instance—yet they still buy from Cargill.

We have done important things trying to get these people out in the countryside, to see ethanol and biodiesel plants, and farms. When these two men from China were working in my office, I took them home one weekend to East Chain. Each had a guest room on the farm. They come from a place that’s very crowded. On our farm, you can look out the window for miles and not have anyone see you. That was a strange experience for them, being in an isolated area. These cultural exchanges are important.

You’ve served as commissioner of agriculture under three administrations: Carlson, Ventura, and Pawlenty. Tell us about each.

An overall comment: All three were (are) different. They had (and have) their strengths, and like all of us, they all had (and have) their weaknesses.

What were their strengths?

I will always be grateful to Arne Carlson for appointing me. Without that, I probably wouldn’t have had the experience later. Arne was a no-nonsense guy. He didn’t understand agriculture, but knew it was important. He did not get in the way. He wanted the job done and was satisfied if you did it. I served just under four years with him. With him came my first opportunity to travel overseas. He gave me free rein, and we had a good relationship. Arne had some unique personal characteristics that others sometimes found difficult to work with. He was very driven, aggressive.

You could tell that by just looking at him.

Yes. He often was heading down the road before putting it in gear.

Jesse Ventura was, by far, the most interesting person I have and will ever work for. During the election, I had been working for his opponent, Norm Coleman. The night of the election, when I saw the vote totals, I began thinking about packing up and heading home to East Chain. The next day, Jim Palmer of the Soybean Growers telephoned. He said, “If some of us would suggest to Gov. Ventura that he keep you on, would you be interested?” The question completely took me by surprise. I had not even considered it. I told him I’d have to think about it. I talked with a couple of my staff members and we figured Jesse had to appoint someone. I called Jim back, and said I’d be interested. At that time, I didn’t have any expectations of being re-appointed.

That Friday, I left for a trip to China. I went to Beijing, and then on to a city about two hours southwest. Stepping off the airplane, I was greeted by an agriculture ministry official.

His first words: “You have a new governor.”

I said, yes.

He said, “He is a wrestler.”

I said, yes.

He said, “Is that real, or is that fake?” (Laughter.) I laughed, and said, “You’ll have to ask him.” While I was away, my staff cleaned up my resume and sent it to the Governor-elect’s office.

As for his approach in selecting commissioners: It’s no secret he was just as surprised as everyone that he won. Yet he needed help. I’ll always give him credit for reaching out to people who were good doing what they did, and doing it for the right reasons. The Ventura administration was non-political to start, mixing Independents, Republicans, and Democrats. It changed later. He had a sophisticated process of picking people. He used headhunters who would give him a final list of two or three people. Then he would do personal interviews.

What about Gov. Tim Pawlenty?

I’d worked with him in the legislature, but not a lot. Again, when he was elected, some people asked if I would consider staying. I said, absolutely. The governor’s chief of staff, Charlie Weaver, called just before Christmas to say Tim Pawlenty wanted to interview me. After flying in from Chicago, I stepped into his transition office, and the governor’s first words were, “We want you to be commissioner of agriculture.” That was my interview. It was short and sweet.

Tim Pawlenty is very bright and has a wide view of many things. He understands that agriculture plays a key role in Minnesota’s economy. Every time a trade mission is planned that could involve agriculture, we are included. Another thing: The governor is a quick study with information. He is open to new ideas—in fact, he demands them. He’s a stickler for making everything better—he’s not necessarily interested in keeping the status quo. He’s not afraid to try new ideas. His E20 and biodiesel approach was unique.

On occasions I’ve given him a five-minute briefing on a topic and he will go out into an audience and deliver an off-the-cuff speech for twenty minutes or longer—and do it on topic, using his vast knowledge to incorporate facts and figures. He’s a magnificent communicator. Some politicians fear being one-on-one and intimate with people in public. He has always relished that, sometimes to the dismay of a staff that tries keeping him on time.

Is ethanol the best use of our water and corn?

To a degree, the water issue has been overblown. Certainly, we have to be concerned. Virtually every new ethanol plant being built uses less water in the making of ethanol than the last plant. The water is being recycled to a great degree. I scratch my head a bit in that Minnesota has raised more issues about water than any other state, and yet we have more water availability than most states. Certainly, parts of Minnesota have to be looked at carefully in terms of water use.

As for corn: People need to remember the current corn price is not totally determined by ethanol use. Speculators are driving commodity markets to a degree I don’t think most people understand. Housing and stock markets are down. People wanting to make money are putting their money into commodities, such as grains, oil, and gold, where more opportunities exist for gain. We’re seeing a huge amount of money shifting into this area. Of course, the only way these people will make money is if prices keep rising. It’s a runaway train.

We all know what will happen. The price will change dramatically. Now having said that, I can understand what these higher prices are doing right now to people, particularly livestock farmers. But for consumers to think ethanol is driving up their food costs, they need to remember that oil prices are affecting the cost of food more than the raw commodity. For instance, I’ve heard estimates that only about 20 percent of food cost increases are attributed to the commodity itself. The rest can be attributed to oil, such as higher transportation costs to get food products to grocery stores, fertilizer, processing costs—all those things take oil.

I hear you saying that rising fuel costs are similar to the water situation. The fears concerning them are a little overblown.

Again, there is concern, yes. I think ethanol and corn prices have become the fall guy. The amazing thing is that when oil prices went from $20 to $30 per barrel, people were up in arms. Now it goes from $70 to $140 and people say, “That corn is causing all our problems.” In reality, if we all stopped making ethanol tomorrow, you wouldn’t see in the long run much change in the price of corn. We’re producing about seven percent of our fuel needs from ethanol. If we stopped making it tomorrow, you would see a sudden rise in petroleum costs because of increasing demand.

Your brother is a Martin County pork producer. How have higher input costs affected his business?

I sell him my corn and, fortunately, he still speaks to me. That’s good news. I know firsthand that rising prices have been an issue. What has been good for many pork farmers in Minnesota is that most of them grow much of their own corn. They aren’t totally dependent on the market. The poultry industry, on the other hand, is having problems. The other thing as it relates to corn and ethanol: We have never said corn was the final answer to making ethanol. Corn is only the transition to other feedstock.

What are the hurdles that ethanol plants must cross in order to convert over from corn to more efficient, non-edible sources?

First off, ethanol plants are as chagrined as hog farmers about corn prices. It’s put the ethanol plants in a difficult situation in the sense they have to buy corn at such a high price. Ethanol prices aren’t as high as they have been, either. Oil prices kind of bring them along, but there’s not the profitability there used to be.

What we see happening—again, as part of the governor’s vision—is a transition to other feedstock. That doesn’t mean we will completely do away with corn and soybeans, but they will not be our major focus down the road.

In ten years?

Five to ten. It’s kind of like which comes first, the chicken or the egg? You can’t produce a lot of switch grass, for example, until you actually have someone burning it. You can’t build facilities to use it until you have growers. It has to be worked at simultaneously. Here is how we’re going to do it: First, use biomass material as the current fuel source for existing ethanol plants. Right now, most of the plants are using natural gas, and we all know what has been happening to natural gas prices. What we are looking at doing is developing an infrastructure to grow, process, and transport this biomass product, and use that to burn in these facilities instead of natural gas. That helps start the process of converting some of the land that right now isn’t doing anything, or is marginal land.

What about the number of distribution points for E-85. Are they increasing?

In Minnesota, they certainly are; nationally, not much. That, of course, is part of the challenge. It’s like the problem of moving to cellulose to make ethanol. Do you increase the number of stations carrying E85 or do you manufacture more cars that can use it? Automobile companies are reluctant. That’s one of the differences between the U.S. and Brazil. Brazil mandates that its new cars are capable of using renewable fuels.

What about algae?

Obviously, we’re going to have to find more feedstock other than corn and soybeans. One promising development in terms of diesel fuel is algae. That technology is being explored aggressively. There may be a time when we see algae farms in Minnesota in areas that are now wetlands. We could be growing algae at the same time as preserving wetlands. It could have a dual purpose.

Do you sometimes feel metro politicians are out of touch with the needs and opportunities of rural Minnesota?

No doubt about it, and yet, in all fairness, many rural legislators are out of touch with some metro needs. There is always a need for understanding.

Give examples.

Most metro legislators’ links to farming—if a link exists at all—is from several generations ago. Adults remember visiting their grandparents’ farm when younger. Agriculture has changed. As agriculture has modernized—very rapidly, I might add—these people say, “This isn’t the way grandpa used to do it. Why do you need 2,000 cows? Grandpa had 20. Why do you need chemicals? Why do you need aerial applicators?”

On the other hand, most rural legislators have never supported light rail, and yet you look at the gridlock that will develop without mass transit.

You are a former president of the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture. What traits did that organization see in you to have them elect you as president?

(Laughter.) I didn’t show up at the meeting in which I was nominated. (Laughter.) We have a situation where we rotate between four different regions in terms of officers. The year in which it was the Midwest’s turn to nominate the person to the rotation, I happened to be in Boznia with the lieutenant governor, missed the meeting, came home, and suddenly learned I was in the rotation. Part of my story in politics can be attributed to being in the right place at the right time. The other thing is I feel I have an ability to work with people in both parties. One thing about agriculture is that it is less political than most other government issues. That is part of the attractiveness in doing the job.

Are you going to retire at the end of Tim Pawlenty’s term?

I have learned to never say never. But I’m realizing at some point I will. Right now I will say my options are open. I have always felt there is life after politics. Right now I’m more a bureaucrat than a politician. I don’t know if I could transition into retirement. We’ll see what happens.

Getting to know you: Gene Hugoson

Born: September 11, 1945.

Education: East Chain High School, 1963; Augsburg College, 1967;

Graduate courses at Minnesota State, 1971-74.

Family: wife, Pat; children: Jon, daughter-in-law Jamie, and their son, Leighton.

RIO DE ETHANOL

CONNECT: You’ve been to Brazil. What can Minnesota learn from Brazil in terms of renewable fuels and energy?

HUGOSON: The Brazilian government owns the oil company. If the government says the oil company must embrace renewable fuels, it does. There is a way to run vehicles on different levels of renewable fuels. Years ago, people said 10 percent ethanol would ruin cars. It didn’t. Some will say 20 percent will ruin cars. We have flexible-fuel vehicles using up to 85 percent.

Watching Brazil, I have a lot of admiration for what they’re doing, The way they have aggressively pushed renewable fuel is noteworthy. That’s one of the reasons Gov. Pawlenty met with the Brazilian ambassador. Yet they have a lot of problems, too. Their infrastructure has a long ways to go. There has always been a distrust of the Brazilians looking to take over the U.S. ethanol market. I think we are getting beyond that distrust, and in the future some cooperation could take place.