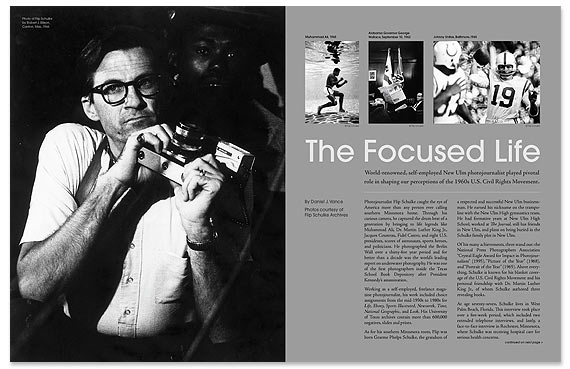

Flip Schulke

World-renowned, self-employed New Ulm photojournalist played pivotal role in shaping our perceptions of the 1960s U.S. Civil Rights Movement.

Photos Courtesy of Flip Schulke Archives (© Flip Schulke)

Photojournalist Flip Schulke caught the eye of America more than any person ever calling southern Minnesota home. Through his curious camera, he captured the drum beat of a generation by bringing to life legends like Muhammad Ali, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Jacques Cousteau, Fidel Castro, and eight U.S. presidents, scores of astronauts, sports heroes, and politicians. He photographed the Berlin Wall over a thirty-five year period and for better than a decade was the world’s leading expert on underwater photography. He was one of the first photographers inside the Texas School Book Depository after President Kennedy’s assassination.

Working as a self-employed, freelance magazine photojournalist, his work included choice assignments from the mid-1950s to 1980s for Life, Ebony, Sports Illustrated, Newsweek, Time, National Geographic, and Look. His University of Texas archives contain more than 600,000 negatives, slides and prints.

As for his southern Minnesota roots, Flip was born Graeme Phelps Schulke, the grandson of a respected and successful New Ulm businessman. He earned his nickname on the trampoline with the New Ulm High gymnastics team. He had formative years at New Ulm High School, worked at The Journal, still has friends in New Ulm, and plans on being buried in the Schulke family plot in New Ulm.

Of his many achievements, three stand out: the National Press Photographers Association “Crystal Eagle Award for Impact in Photojournalism” (1995), “Picture of the Year” (1968), and “Portrait of the Year” (1965). Above everything, Schulke is known for his blanket coverage of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and his personal friendship with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., of whom Schulke authored three revealing books.

At age seventy-seven, Schulke lives in West Palm Beach, Florida. This interview took place over a five-week period, which included two extended telephone interviews, and lastly, a face-to-face interview in Rochester, Minnesota, where Schulke was receiving hospital care for serious health concerns.

Your grandfather was founder of Adolph Schulke and Sons Department Store in New Ulm. In 1946, at age 15, didn’t you leave your family and home to live with your grandmother in New Ulm?

In January 1946, I left Cornish, New Hampshire, where I lived with my parents. I took a train all the way to New Ulm, even though I really didn’t know anyone there that well. My father had never talked about New Ulm, which was kind of strange because he had starred on the New Ulm basketball team that played in the 1918 state championship game. He was a big sports hero. He then received a scholarship to the University of Wisconsin, which meant he would leave New Ulm and the family business. In his absence, my grandfather and my father’s two brothers continued running the department store. Born in Germany, Grandfather Schulke died in 1932 when he was just getting going in business. I was born in 1930, and so I didn’t know him.

On my mother’s side, my great uncle had been the male secretary of James J. Hill, one of the great railroad company barons of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. My mother’s father, Paul Kalman, along with his brother, helped form the first trust company in St. Paul. They were Jewish.

When did you learn you were one-fourth Jewish?

When did I learn? I learned right from the beginning, because my father was anti-Semitic. Why he married my mother I will never know. As for my mother, she became completely deaf at age 16 from scarlet fever. Her father sent her to a school out East that taught lip reading. She went through that schooling and came out a whiz. I could be driving a car and talking and she could read my lips from the side.

Why come to New Ulm? Did you have family problems?

I was a skinny and sickly kid. It seemed I was always sick in bed. My father had been a big athlete and basketball player. I couldn’t do any of the sports he wanted me to do—and he forced a lot of sports on me. I tried, but he said I wasn’t giving enough effort. I wanted to please my father, but couldn’t. I embarrassed him. There’s no getting around it. I didn’t live up to his expectations.

My oldest sister, Roxanna, now 78—I just love her. She and her husband have homes in Montreal and Bermuda, and she is a self-made millionaire. As a child, she always had the energy I didn’t have. She was the captain of every sports team. It was her personality to be the captain.

I ran away to New Ulm because everything at home was turning negative towards me. In late 1945, my parents were no longer taking me to high school and I didn’t have any way of getting there. My sister Roxy was sent to the private Westover School, a really fancy place. She was queen of everything. I’m not jealous—again, I love that girl.

Anyway, by January 1946, I was getting angry. Our home had a wood furnace, and I was told I had to stay up all night, every night, to keep that furnace burning. My father wanted me sleeping only four hours a day because he had all these other chores for me. The way I was treated that last year was disgusting. I think all his behavior was the result of his becoming an alcoholic. He died of cirrhosis of the liver at age 50.

Was it your tough upbringing with your father that gave you a special love for the underdog?

Certainly, because he was so terribly anti-Semitic. When my wife and I moved to Miami Beach in the mid-1950s, I saw “Gentile Only” signs on some of the businesses. There were lots of Jews living there. Everything I witnessed about certain groups of people was opposite of what my father had said about them. I couldn’t understand why the Seminole Indians had been thrown out of Florida. When younger, I made friends with black children and didn’t find them any different.

So you ran away from home?

My father used to carry a lot of money around in his pants pocket. Early one morning I picked out several hundred dollars from his pocket, which was enough for a train ticket and more from New Hampshire to New Ulm. My Grandmother Schulke and Uncle Fred had gone back to live there. Fred was the oldest of my grandfather’s brothers. My grandmother rented an apartment in New Ulm. She didn’t know I was coming and my parents didn’t know where I was. When the train stopped in New Ulm, I asked some people where Mary Schulke lived, the wife of Adolph. He had been a great man, was friendly, and had given people food during the Depression. Later, a lot of people in New Ulm came up to me just to say they knew my grandfather.

My grandmother loved me. I had lived with her a couple of years earlier when my father wasn’t getting along with me. Though having learned from my parents that I was missing, she said I could stay with her in New Ulm and attend school there. Three months later she died. Just months after that Uncle Fred was committed to an institution after being discovered wandering the streets with dementia—in Massachusetts.

So you were all alone in New Ulm at age 16?

That summer I lived in my grandmother’s apartment building and slept in the attic. It was awfully hot. That fall the landlady offered me a room in the basement next to the furnace and I fixed it all up. I am a total German, meaning everything has to be eins, zwei, drei—in order. It was built into my genes. I wasn’t taught it. That is the way people in New Ulm were then. It has changed a bit now that people from the outside have moved in. The basement was warm, and had an automatic furnace and I was happy living on my own. I didn’t attend school in the spring of 1946, and I needed money because I had nothing.

What about school?

The school wouldn’t let me register that fall. They said an adult had to register for me. Lo and behold, and without my knowledge, one of the lawyer friends of my father decided I had a lot of gumption—and he didn’t like my father at that point anyway—so he decided to sign all the papers and put me in school. But I signed all my own report cards.

In New Ulm, you worked for The Journal. From there, you went to Macalester College, where eventually you were named College Photographer of the Year for the entire nation.

I won College Photographer of the Year in 1952, and because of it was allowed to attend a Missouri workshop involving professional photographers. When there, the way I chose my agent was almost like throwing darts. I liked the name Black Star Agency and they wrote me back a very encouraging letter, which I learned twenty years later was the same letter they wrote to everyone asking about their services. My first assignment through them involved New Ulm. The U.S. Information Agency was looking for ways the U.S. could make friends with Germans overseas. One of my suggestions was to photograph my hometown, where people still spoke German, had polkas, and drank beer at beer halls. They thought that was great. I went back to New Ulm for five weekends and shot everything. USIA was happy with it, and that was the beginning of my career. The photographs appeared overseas in Germany. I was the first person from a small college to win College Photographer of the Year.

Who was Wilson Hicks? Why and how did he mentor you?

After graduating from Macalester College, I went to the University of Miami to teach. In the years following, while I was also working as a free-lance magazine photographer, everything in society there seemed to hit the fan, including Fidel Castro and segregation. Life moved a bureau to Miami that included two staff photographers. Charlie Moore and I were their two freelancers, and we were the ones doing stories on segregation.

Wilson Hicks had been the picture editor of the Associated Press in the 1920s, and had been the picture editor and executive editor for Life for about twenty years before retiring. He was coming to the University of Miami to speak. I had read his book Words in Pictures, and similar to what I did later with Dr. King’s book, had underlined many passages. When I read books, I like asking people why they say certain things. The night I met him, three or four other photographers were fawning all over him. I just went up to Wilson and said, “I have your book and would like you to explain certain things you said. Do you have the time?” He told me to come to his house in a couple days. I took along my photography portfolio and he went through picture-by-picture and criticized each one. He said how I could have improved each picture. Criticism should be more than just telling someone whether you like or dislike a photo. You have to tell them why you don’t or do like something. He was intrigued with my photography.

He taught me that at times you have to overwhelm people to get photographs, but in general I found that sweet-talking was best. That fit my personality. Hicks had the ability to read a person’s temperament. He treated me with kid gloves and never yelled at me, although I talked to some Life staffers and they said he could get really mad.

With Life, he put the notice out that writers, usually young hotshots from Harvard or Yale, weren’t the ones really in charge of an assignment. They were hired more as “caption takers,” and were assigned to a photographer. Wilson told the photographers that they (the photographers) were the ones in charge on Life assignments, no matter what the writer said. If you didn’t come back with pictures, your career was over with Life. It was so competitive, and everyone wanted to work for Life.

Why decide to be a freelance magazine photographer rather than be directly employed by a magazine?

The big advantage was having ownership of my work. If I had been an employee of a company, that company would have 100 percent ownership of my work. If I had gone to work for Life—it was the greatest place in the world to work and I was offered a job there—but besides not retaining ownership of my work, I would have had to move wherever they wanted. By then I was working for the University of Miami, married with four children, and had a nice house. I wasn’t about to go to New York.

As for work, I’m a master of ideas. Back then starting out I would get photography ideas from the local newspaper. Magazine editors in New York didn’t read the Miami Herald, yet Miami was a hotbed for all kinds of things going on. For instance, we knew of Castro long before the people in New York did. Eventually, Life started a bureau in Miami, and I was a freelance photographer attached to the bureau. Every picture I took for them was my property—something they didn’t think about then, because no one was thinking about the re-use of old pictures.

Name some magazines you eventually took pictures for?

Back then, Life, Look, Time and Newsweek were the four big magazines. I also worked for Sports Illustrated and became a very good sports photographer. I had one particularly special picture in Sports Illustrated of Johnny Unitas. I’m interested in practically everything and didn’t want to be known as specializing in any one kind of photography.

The closest I came to being known for one kind of photography was my underwater work. I took an underwater picture of a killer whale for National Geographic, back when that magazine was trying to get me to join their staff. Later I approached National Geographic with the idea of taking an underwater photograph of a water skier. They thought my idea was ridiculous, so I pitched it to Life, and they went bananas over it. To be honest with you, in taking pictures underwater I didn’t give a blessed heck about the flora and fauna. My interest was solely with what human beings were doing underwater, and their interaction with larger mammals.

But you are still known by many for your underwater photography.

I invented a fish-eye lens utilizing Nikon’s fish-eye lens, which initially was invented to photograph the entire sky for astronomers. As for my underwater photography, I learned from Jacques Cousteau to use incandescent lighting. I used yellow, 1,000-watt lights, and had a generator in my boat and a long cable. I invented all this for underwater photography, but didn’t want to be known for it.

My water skiing photos for Life won first place in the National Press Photographers sports photography contest. After that, Sports Illustrated asked me to do a color portrait of Muhammad Ali for a story they were writing. To expand the assignment, I asked them if I also could take pictures of Muhammad Ali underwater. The editor thought I was insane. I asked for permission to take my idea to Life, and he said that if they were crazy enough to sign it, then fine. The Life editor thought it was a great idea. Not only was the Life photo great, but also it hit the streets a week before Sports Illustrated’s story. I shot Muhammad Ali standing in a pool. My idea was to have bubbles showing the different movements of his fists. Life and Sports Illustrated, though friendly to each other, also at times competed like children. When Sports Illustrated had begun, it had hired four of the greatest sports photographers away from Life. Thus began the competition.

Some people you photographed?

Roy Campanella was my first cover for Ebony magazine. He was the catcher for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1955 when they won the World Series. Everything was segregated back then, and I photographed Campanella the next year on a fancy yacht, near where the Dodgers trained in Vero Beach. I worked with Jacques Cousteau on the Calypso. I photographed presidents Kennedy, Eisenhower, Truman, Johnson, Nixon—eight in all. I had eight covers for Life magazine. As soon as you did a job for Life, you never needed to send an editor a portfolio. If you worked for them, editors figured you must be the best.

I never worked for a newspaper, only magazines.

I did the first astronauts, Shepard and Glenn. On some early launches, I was the photographer assigned to be with the wife in Houston. Cooper was the last of the original Mercury astronauts to fly, and Julie Cooper was a sweetheart. At home I have a list of names two pages long of people I have photographed and you would recognize every name. I was a photojournalist covering current events, and thirty years later current events becomes history. Through Ebony magazine, I met the leadership of the black community in the South.

Give examples of the physical dangers involved in being a news photographer?

The list is terribly long. The first is just busting up your body doing crazy things. I never broke a bone in my career, but was known for climbing all over the place. I stayed skinny until I was about sixty, and could inch or worm my way into anything, which was a great asset as a news photographer. My worst fear was being out in the field and falling off a high place.

What kept me from getting killed was thinking about the dangers. Can I go there? Is it safer over there? I was extremely lucky. The most dangerous situation I was in was when Dominican Republic rebels lined us up to be shot. A Peace Corps doctor saved us. We were there three or four days before the U.S. troops landed. After we were saved, I decided no more war photography for me. I wouldn’t cover another war, not even Vietnam.

What makes a great news photographer?

I made friends with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and through him I was privileged to learn in advance what he and others were going to do. The big thing about being a photographer, versus a writer, is that a photographer must be on the spot where the action is going to happen before it happens. Newspaper reporters, many times, are also there when the action happens, but they can go down later to ask questions. Photographers can’t do that. You either get the photo when the action happens or you don’t.

I had the ability to anticipate events, but it wasn’t a psychic ability. I questioned everything. I had a very good education at Macalester College. In college I loved history, sociology, journalism, psychology, and philosophy. Sociology and psychology helped me more in my career than anything I learned in journalism class. Through my photography, I wanted to show people what they couldn’t see, or have the ability to see, or to show them someone who normally wouldn’t let people near them.

You authored three books about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

I could take a long time saying everything I liked about him. He trusted me from the minute we met. I was a white man. I met him after he gave a talk in Miami in 1958, and he asked me to go to a certain minister’s house where we could talk later. There, I took his book with me, with passages I had underlined and I wanted to ask him questions about the passages. At the minister’s house, he said that I’d have to wait until the minister and his wife went to bed before we could talk. So Dr. King and I began talking at about 2:00 am, and spent the hours until dawn discussing philosophy, sociology and what he wanted to do with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. I can’t explain it, but from the beginning there was a level of trust and acceptance between he and I. I could see it in his eyes. From then on I had his private telephone number and that of other black leaders, including Rev. Abernathy. They all helped me. I wasn’t with Dr. King all the time because of the death threats.

At his funeral, Mrs. King insisted that I travel along with her and the children to the cemetery. When the limousine stopped, I started going over toward the other photographers. But Mrs. King wanted me to stay with her. That’s why I was able to photograph her and Harry Bellafonte from so close, because I was directly in front of them. Later I used a wide-angle lens to photograph the casket going into the ground.

Did you retire too early?

You have to define that. To most people, that question means having a job and retiring on a certain day. Basically, I was a free-lance photographer, but only retired (in my 50s) from taking photographs. I still had my archives. I quit taking photographs when I felt I didn’t have the energy or desire to do something new or great.

Technically, my last photography assignment was in 2002. In 1968, divers from the University of Florida found in the Aucilla River (in northern Florida) a complete mammoth skeleton, including the tusk. National Geographic paid to have me spend a week there and I photographed it using a special 180-degree lens. In 2002, the Palm Beach Post reported that the University of Florida had mounted the old mammoth, so I went back to shoot it thirty-four years later. That was my longest assignment, and last.

You’ve had a number of physical challenges in life.

I started having leg pains in 1965, which turned out to be two ruptured discs. I was only thirty-five-years old. The Miami Dolphins team surgeon, one of the first surgeons using micro instruments, operated on my back. Essentially he glued together two vertebras and within one month I was in Australia doing photography for a book on the Great Barrier Reef.

Between 1965 and the mid-1980s, I was having leg pains after working all day, but I could sit in a hot tub and the pain would just go away. In the early 1990s, I was mistakenly prescribed a certain heart medication while taking a popular cholesterol-reducing drug. (As a reaction to it) in a short time I went from walking to not being able to walk. Everything hurt so much. I can’t stand up now for only about thirty minutes before my spine just collapses. In 2000, I got diabetes.

It’s horribly frustrating. I was very active my whole life, and could even climb a coconut tree. Then I put on weight because I couldn’t exercise. With the work I did I was always on my feet, and because of it stayed skinny. I was the skinniest guy at New Ulm High School, but now at reunions I’m not.

You have the world’s largest private collection of U.S. civil rights photographs?

My collection of 600,000 negatives, color slides and prints, and 9,000 selected digitized photographs, was given under contract to the University of Texas, which owns the physical possession. I own all the copyrights. They cannot publish or display a single picture that I haven’t authorized.

I went with my collection to the University of Minnesota first. But the grant came from the vice chancellor of the University of Texas. Ironically, five years later, that man became chancellor at the University of Minnesota. I had tried the U of M, but there was a man in charge of those kinds of collections then and he said my photographs weren’t history. I could have strangled him. That hurt because I really wanted my collection in Minnesota. I had thousands of pictures to organize and copyright. Most of the collection was in black and white.

In short, I donated the pictures to Texas, but for usage only with educational institutions in exhibitions. The exhibitions have to be shown as units, not just a single picture. They can’t rent the show or a picture, especially to any commercial enterprise. They own the possession, but not the copyright, and all the photographs are copyrighted. If for some reason Texas wants to get rid of the pictures, because for the most part they don’t involve the history of Texas, they can sell their part, but only to a recognized college. Besides Texas, Macalester College received money for a grant so I could donate them 6,000 digitized pictures.

What about having a permanent exhibit in New Ulm?

New Ulm exhibited my work in 2001, and they will one day have the same exhibit. I want to fix up the photos, but now I can’t work as fast as I used to work. New Ulm has a sidewalk of honor downtown, and a sculptor has sculpted my face in bas-relief on the ground along with the faces of two others. My quote along with the sculpture: “If you find a job you love, you never work a day in your life.”

Getting To Know You: Flip Schulke

Born: June 24, 1930

Residence: West Palm Beach, Florida

Wife: Donna

Education: New Ulm High School, 1949. Macalester College, 1954. Rider University and Macalester College, Honorary PhDs

Books: Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Documentary, Montgomery to Memphis (1976); King Remembered (1986); and He Had a Dream (1995). (All books published by W.W. Norton & Company.) Also, Underwater Photography for Everyone (Prentice-Hall, 1976), Muhammad Ali: The Birth of a Legend, Miami, 1961-1964 (St. Martin’s, 2000), Your Future in Space (Crown, 1986), and Witness to Our Times (Cricket Books, 2003)

Awards: Crystal Eagle Award for Impact in Photojournalism, from the National Press Photographer Association (1995); First Annual New York State Martin Luther King, Jr. Medal of Freedom (1986); Golden Trident, from the Government of Italy for accomplishments in underwater photography (1983); and Underwater Photographer of the Year—USA, from the International Underwater film and photography competition (1967)

© 2007 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Flip Schulke’s work for the Environmental Protection Agency’s photodocumentary project DOCUMERICA can be viewed online in ARC (Archival Research Catalog) at the National Archives and Records Administration web site (http://www.archives.gov/research/arc/topics/environment/documerica-photographers.html)

The ARC catalog contains Schulke’s work in the Florida Keys, New Ulm, Minnesota, and other locations.

In reference to the above comment: The US National Archives Flickr stream has a selection of these photos. http://www.flickr.com/photos/usnationalarchives/sets/72157624339813980/with/4727564962/