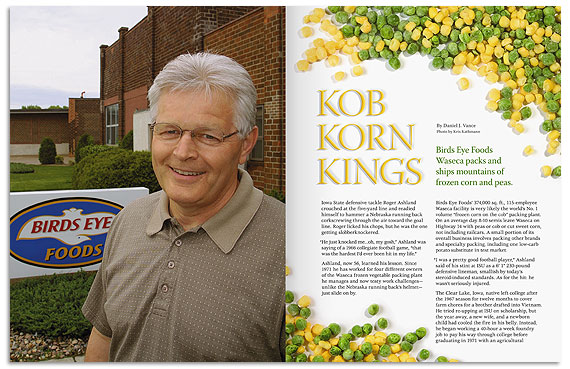

Birds Eye Foods

Photo by Kris Kathmann

Iowa State defensive tackle Roger Ashland crouched at the five-yard line and readied himself to hammer a Nebraska running back corkscrewing through the air toward the goal line. Roger licked his chops, but he was the one getting slobberknockered.

“He just knocked me…oh, my gosh,” Ashland was saying of a 1966 collegiate football game, “that was the hardest I’d ever been hit in my life.”

Ashland, now 56, learned his lesson. Since 1971 he has worked for four different owners of the Waseca frozen vegetable packing plant he manages and now testy work challenges— unlike the Nebraska running back’s helmet— just slide on by.

Birds Eye Foods’ 374,000 sq. ft., 115-employee Waseca facility is very likely the world’s No. 1 volume “frozen corn on the cob” packing plant. On an average day 8-10 semis leave Waseca on Highway 14 with peas or cob or cut sweet corn, not including railcars. A small portion of its overall business involves packing other brands and specialty packing, including one low-carb potato substitute in test market.

“I was a pretty good football player,” Ashland said of his stint at ISU as a 6’ 1” 230-pound defensive lineman, smallish by today’s steroid-induced standards. As for the hit: he wasn’t seriously injured.

The Clear Lake, Iowa, native left college after the 1967 season for twelve months to cover farm chores for a brother drafted into Vietnam. He tried re-upping at ISU on scholarship, but the year away, a new wife, and a newborn child had cooled the fire in his belly. Instead, he began working a 40-hour a week foundry job to pay his way through college before graduating in 1971 with an agricultural business degree. Ashland has been based at the Waseca plant his entire working career, climbing his way up from an agriculturalist handling growers to being plant manager the last seven years.

“We contract with growers within a 45-mile radius,” Ashland said from his Waseca office nearly on top of DM&E’s tracks a block south of U.S. 14. “We don’t have many growers north of Waseca. So it’s really a semicircle including St. James west and south to Austin.”

Birds Eye Foods agrees to pay local growers meeting acreage requirements an amount for each ton of sweet corn or peas harvested. Birds Eye then provides seed, sprays for disease and insects, and harvests; the grower does the fieldwork, plants and cultivates.

So how can Birds Eye compete with $10 soybeans? “This year we’ve held our price and that has made [getting grower contracts] a little more difficult,” he said. “But we have long-term relationships with most of our 200 growers, with some of our relationships dating back 50 years. You see them at spring and harvest and they are really great people. I started years ago dealing with their grandfathers and fathers and now we deal with them. I hate to single out any one grower because they are all great people, from St. James to Lake Crystal to Janesville to Waseca and all over. On average our growers have been with us 15-20 years. We take pride in treating them right and try to harvest their fields just as if they are our own.”

Competition among packers for vegetables—and to that end the hearts and minds of growers—is steep in southern Minnesota. Owatonna Canning lies east and larger Seneca Foods plants southwest (Blue Earth) and northwest (Montgomery and Glencoe).

When Ashland began his career the Waseca plant was owned by General Foods, which became Kraft General Foods, which became Kraft Foods. Dean Foods acquired the plant in 1994 before selling to cooperative Agrilink Foods in 1998. On August 19, 2002, according to Birds Eye Foods Inc.’s most recent 10-K report, “a majority interest in Birds Eye Foods was indirectly acquired by Vestar/Agrilink Holdings LLC and its affiliates.” Stock of the billion dollar company is not publicly traded.

Laughed Ashland, “I’ve worked for four companies (in my career) and never moved.”

Bringing In The Peas

“The harvest is really exciting,” said Ashland. “You have only 24 hours or less to harvest peas, the window is that small. You can get three inches of rain and still you can’t stop. We have to make our pea combines as ‘muddable’ as possible.”

Each year Birds Eye Foods Waseca harvests 20 million pounds of peas and another 80 million pounds of product ending up as either corn on the cob or cut corn to be frozen, packaged in poly bags and shipped to warehouses the U.S. over. Its “ag shop” has nine full-time, year-around employees to maintain and fix combines and lead the annual charge through southern Minnesota fields.

Harvesting peas and corn doesn’t come cheap. A new pea combine can cost $450,000 and “we have twelve, including a few older ones we use as spares,” said Ashland. New corn combines are $250,000, of which Birds Eye has eight.

As for why growers sell to Birds Eye, Ashland said there isn’t much difference between his company’s price and that of any other packer’s. “Our (sales pitch to growers) boils down to treating them right,” he said. “Growing for us or any other company—it’s about the same for any grower. But we like to think we do the best job harvesting. We train our maintenance crews to make sure they treat that field as if it’s their own. Do we screw up sometimes? Yeah. But then we try to be fair to the grower, treat them right, make adjustments if it’s our fault. It’s no different than when I go to the store to buy Birds Eye or Green Giant. If the product is good and it treated me right, I’m going to keep going back. If not, then I’ll buy something else.”

A good harvesting crew can make a grower money—or cost him. For instance, an inexperienced pea combine driver could lose product by setting the “head” too high, spinning the “fingers” on the pod strippers the wrong speed or incorrectly having the “fan” sucking out good product. An inexperienced corn combine operator could lose ears through “stripper plates.”

“Having an experienced harvesting crew is so critical,” said Ashland. “We have about 30 part-time people that help with pea harvest and mostly our nine full-time shop employees do corn picking and maintenance. They do a super job. It all boils down to having experienced people to give a grower maximum return.”

Birds Eye has a “quarter century club” of more than 30 employees with 25 years experience, which represents about 25 percent of its full-time workforce. Ashland said that Birds Eye employees have a “can-do” attitude typical of people in Waseca. “They will do whatever you ask them, and always want to do a better job,” he said. “Our outstanding 100 or so full-time people make the plant run efficiently and train all the summer help.”

Not everyone has experience. To meet production demands, Birds Eye must hire 200 temporary workers annually for pea and sweet corn packing. The job of recruiting becomes more difficult each passing year. Since 1996, most have been migrants from Texas and Mexico, with about 30 percent of the original ‘96 group returning every year. This “core group,” said Ashland, has helped operations by communicating their experiences and company procedures to newer, non-English speaking workers.

“Developing and maintaining good communication [with Hispanic employees] is one of our biggest issues,” said Ashland, “and it is improving. Our Hispanic employees are super workers and fun to be around.”

As for employees, the company over the years has progressively done more with less. For example, in the “cob select” area: Birds Eye used to have eight tables and eight employees at each, requiring 64 workers per shift. With the recent purchase of a semi-automated cob saw, now 16 workers per shift process the same amount of sweet corn.

When Good Is Bad, Bad Good

Billion-dollar Birds Eye Foods has 15 plants packing everything from Husman’s potato chips to Snyder of Berlin pretzels. But its three frozen food plants—in Waseca, Wisconsin and New York—are its bread and butter. The company has spread out its frozen food plants to spread risk: If a weather disaster hits Wisconsin, for instance, the tonnage from New York and Minnesota gets the company through.

“Even in our area, which is almost 100 miles across, there is a big variation in weather,” said Ashland. “Since I’ve been here the least amount of corn we’ve harvested has been about 85 percent of our objective. Corn isn’t affected that much by weather. But peas are just the opposite, more volatile, more weather-dependent. We’ve had as little as half a crop and as much as one and a half.”

So bad years are really bad, right? Strange as it seems, said Ashland, the bad harvest years are often his plant’s best. When supply falls nationally, Birds Eye can raise its wholesale prices to retailers accordingly.

Said Ashland, conversely, “A really good year sometimes is your worst. If there is too much product on the market you may have to [lower wholesale prices to retailers to sell it] because monthly cold storage costs are so high. This chips away at profit. The best scenario for our plant is that we have a great year locally and all packers nationally have a bad year. This has happened but the opposite has too. Several years ago this area had a lot of rain leading to a horrendous pea crop and everybody else had an average crop.”

That is the ongoing risk of business, he said, and the primary reason why Birds Eye Foods has pea and sweet corn plants in different growing regions. The strategy has worked: Birds Eye Foods is the No. 1 volume frozen vegetable brand in the U.S.

Slicing And Dicing Costs

“My philosophy—and I believe that of everyone here—is Waseca should be Birds Eye’s premier plant hands down. We try to have the lowest cost and highest quality,” said Roger Ashland.

To that end, the management philosophy of Birds Eye Foods provides Ashland and his team a degree of autonomy to make cost-cutting and quality decisions. “We have a great deal of local control,” he said. “I report to an executive in Michigan and I may see him only once every three months and talk with him five minutes weekly. We do correspond via 10-15 short emails weekly. With this company you really are in charge of your own destiny.”

Its largest cost apart from employee wages and benefits by far is electricity, nearing the $1 million mark annually, which is needed to freeze peas and corn in summer and fall. Their power supplier, Xcel Energy, offers a “very reasonable” rate during the peak packing seasons.

Ashland said, “To come up with ideas to conserve energy we have an energy conservation committee meeting eight times a year. They make sure we do the simple things, like close the doors in winter, use high-efficiency motors, and bring in high-efficiency lighting. Nothing in this business is really too rocket science. It’s just doing basic things and doing them right.”

As for maintaining product quality, anyone entering the Waseca plant must first walk through a half-inch pool of antibacterial liquid. The American Institute of Bakers regularly inspects the plant for bacteria and rates the facility.

Where’s The Cool Whip?

We started making Cool Whip at this plant in 1966 and continued until 1996. A lot of the initial testing for it was done here. At one point, half the Cool Whip in the nation was made in Waseca. —Roger Ashland

Waseca Terrorism Alert?

“Since September 11 one of our concerns is that terrorists might try to contaminate or poison our food,” said Roger Ashland, plant manager. “Often we think, What could happen in little old Waseca? Yet we’re known as America’s No. 1 frozen brand and we have to be careful. In fact, we now have a vice president of security whose only responsibility is for plant security.”

A Field Too Far

When at Harold Schmidt’s farm during corn harvest one year, I filled in for a pick operator while he ate lunch. I began picking and at the same time began talking to a guy sitting with me in the combine. While picking I was also conveying the corn onto a truck moving beside us. I wasn’t paying attention to the corn because I was talking too much. I missed the truck all the way down the field. Thank goodness it was a short field. Harold Schmidt was standing there, and he said, “Roger, that just goes to show that some people like you are meant to be field men, others are meant to be field picker operators.” We picked it all up by hand. —Roger Ashland

Watching Peas And Q’s

Perhaps it’s the idea of a repetitive line of yellow cob corn on a conveyor belt or a pile of steaming green peas naked on white china. There is nothing special or sexy about vegetables.

Roger Ashland said some locals think the same of his plant—the one that has brought good jobs to this city for 75 years. Said Ashland, “We’re taken a little bit for granted. It’s the same as having been married 40 years. Sometimes you take your spouse for granted, too.”

Then he back-pedaled a bit. “However, most of the town understands what we do,” he said. “There really is lots of support and we are an important part of the city. The only negative I hear about our operation is the odor, which is going to happen when you’re processing any fresh product in volume. We’re working to minimize it.”

Ashland admitted that sometimes Birds Eye Foods gets lost in the shuffle in a town that has Brown Printing (1,000 employees) and Itron (600 employees).

“We’ve been here 75 years and hopefully another 75,” he said.

© 2004 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Is any of Bird’s Eye’s corn GMO? We really like Baby Gold and White Corn but are scrupulous about avoiding GMO foods.