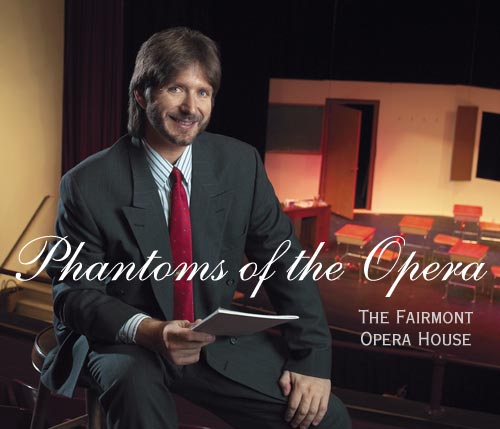

Fairmont Opera House

Photo By Jeff Silker

Friendly ghosts inhabit the Fairmont Opera House. Maybe true, maybe not, but it’s Michael Burgraff’s way of explaining certain fortuitous events which occur on the premises. “The ghosts take good care of us,” said Burgraff, who is managing director of the 98-year-old facility. Restored to elegance, the opera house has been described as a “runaway locomotive” because of its rapidly increasing popularity.

Opened in 1902 by promoters who wanted to put Fairmont on the cultural map, it serves much the same purpose in this new century. Besides providing entertainment, it’s employed as a recruiting tool when the community seeks new doctors, industry executives and other professionals. “The message is that we may be out here on the plains in the southern part of the state, but we have five lakes, a shopping mall, an aquatic park and cultural entertainment,” Burgraff said.

Bob Wallace, president of the Fairmont Area Chamber of Commerce, views the opera house as “a tremendous asset. It’s one of the things that sets us apart from other communities. It’s one of the three major ‘draws’ which bring people here. The others, Fairmont Raceways and our new aquatic park, are seasonal, but the opera house attracts people throughout the year.”

Many rural communities built opera houses around the turn of the century, but most have been converted to other purposes or consigned to abandonment, musty and decaying. Fairmont’s, however, has been in a continual stage of renovation for the past 20 years. It was originally built by public-spirited citizens and had its grand opening to a packed house Feb. 11, 1902. That audience paid $5 a seat to see “The Chaperone,” put on by a traveling company of 100 players. After 10 years, it passed into private management, operated by Billy Hay and W.L. Nicholas, and began to show talking movies. Hay’s death ended that partnership in 1926. The facility had its second grand opening in July 27, 1927 as the Nicholas Theatre after interior remodeling made it suitable for both movies and live theatre. But it was used exclusively for movies from 1927 until it closed in 1980. Shortly thereafter, a community group stepped in, formed a nonprofit corporation, bought the building and began an on-going renovation.

When Burgraff became the opera house’s first (and only) full-time employee in 1997, it had an annual operating budget of $63,000 and staged only a handful of shows each year. “The average attendance was 60, no matter what played,” Burgraff said. Now the opera house sports a $250,000 budget, brings in nine productions a year and sells virtually all 506 seats for each performance. There are workshops and special shows for youngsters. There are New Year’s Eve stage shows, followed by a dance and show downstairs in the Footlight Lounge.

“I was told that the town would in no way support anything with a ticket price over $10, but this year we’re selling individual tickets for $18,” Burgraff said. “As we’ve increased the quality and caliber of our productions, the town seems to have come right along with us.”

The opera house fills its traditional niche by importing talent, musicians, vocalists, bands, orchestras, dancers, comedians, magicians and hypnotists. It operates a children’s theatre department, organizing two productions every year involving youngsters. But it’s moved in nontraditional directions during the past three years to evolve as a gathering place and focal point for the community. In terms of finding innovative uses for the facility, Burgraff said “your imagination is your limitation.” The facility has hosted two high school proms, one wedding, several wedding and funeral receptions, numerous seminars and business meetings, even a couple of customer appreciation events staged by local businesses. “This rental part of the business has gone through the roof,” Burgraff said.

Before Burgraff arrived, the opera house was used about 90 days in a typical year, with 60 of these days taken up by the Civic Summer Theatre, a separate organization. Now something is happening at the rate of 290 out of every 365 days. All this activity caused some board members and residents to characterize the operation as a “runaway locomotive,” creating a concern that maybe there’s now ‘too much wear and tear” on the facility and producing a few “growing pains,” according to Burgraff.

But the increased tempo also led to questions like “where’s our future?” and engendered a planning process for the future. Burgraff developed a one-page “vision statement” looking forward five years. “Instead of being a runaway train, we’re just on a fast track,” he said.

Worries about wear and tear, especially on the lobby carpet, were tempered by the observation of Fairmont native Warren Nelson, who now operates the Lake Superior Big Top Chautauqua Theatre in Bayfield, WI., and has brought shows to the opera house. “Good,” he told board members. “It means it’s being used like it’s supposed to.”

Burgraff, still the opera house’s only paid employee, deals with the growing pains as best he can. He stretches himself to handle multiple tasks, sometimes hiring strong backs to load and unload the equipment and props of visiting artists, sometimes contracting with companies to run the sound system for performances.

When he interviewed for the job, he understood the organization had 250 people signed up as stage hands. “Great,” he thought. “They’ll be a big help.” He later learned “Stage Hands” is the name of the opera house’s women’s auxiliary and most of the 250 members are 50 or older. “They’re not much help loading or unloading equipment,” he laughed.

“One day last week we were selling tickets for five different performances and we ran short of box office volunteers,” he said. He tried switching a telephone line to the Fairmont Chamber of Commerce office to handle some of the ticket inquiries. “After three days, chamber personnel decided they just couldn’t handle it. The volume was too much.”

So far, the ghosts haven’t stepped forward to relieve these growing pains. But they’ve delivered other miraculous favors. Last September, members of a Scottish dance troupe pleaded with Burgraff to “do something” to cool down the stage because they were sweltering while performing. “I explained there was nothing that could be done because the stage is neither air-conditioned or heated. But after the show, they thanked me for creating a steady breeze that kept them cool,” he said. No doors or windows had been opened, no fans used. “It had to be the ghosts,” he said.

Last year, they rescued Burgraff from possible serious injury while he was installing new lighting. Alone in the building, he’d climbed to the top step of a ladder (the step which is labeled “not a step”), then stretched to reach a fixture. “The ladder teetered and I slipped forward. I should have fallen down into the seats, but didn’t. It was the ghosts again,” he said. “I climbed down and said ‘thank you’ out loud, even though there was no one else in the theatre.”

In opera house lore, the spirits also receive credit for an immensely important discovery early in the restoration process. Many of the decorative plaster reliefs which embellish the theatre’s walls were damaged beyond repair and the board had decided restoration or replacement would be too expensive. “Then volunteers wading through years of junk in the basement came to the very back corner and found several unopened crates,” Burgraff said. “They popped open the crates and found extra copies of all the plaster reliefs, brand new from 1902. The builders must have thought they’d be needed someday.”

Burgraff identifies the friendly spirits as those of Bob and Mary Arneson, who instigated the preservation and restoration of the opera house in 1979 and died in a 1984 auto accident, and Alyce Bachman, a longtime board member who died of cancer in 1998. Because of their intense dedication to the project, they’ve become part of the lore and mystique surrounding the opera house.

Had it not been for the Arnesons, Fairmont might have lost this precious asset, now listed on the National Register of Historic Sites. Run down, threadbare and decrepit, its long service as a movie theatre ended by changing times, it barely escaped being bulldozed for a parking lot.

Driving by the forlorn structure, one of the Arnesons’ youngsters reportedly observed that “if we let the opera house be demolished, then all of Fairmont can be demolished. We need to save it, so Fairmont can go on.”

Led by the Arnesons, a nucleus of Fairmonters formed a nonprofit corporation in 1979 to buy the building, which had operated as the Nicholas Theatre for years, from Charles and Ruby Nicholas. That purchase was accomplished for $51,000 in November of 1980 and by May 3, 1981 the theatre had been reopened for its first live performance in many years, “Another Opening? Another Show,” featuring local talent.

After that introduction, people could see the property needed attention and volunteers began to emerge. During the next two years, the roof was repaired and reshingled, the brick exterior sandblasted and tuck-pointed, the ceilings insulated and a sprinkling system installed. These improvements, plus retiring the brief mortgage on the building, came to $144,000, raised through individual and corporate contributions. Community interest was obvious by the 10,000 hours of volunteer labor and by such donations as a fireproof grand drape for the stage. By 1986, nearly 1,200 workers volunteered in excess of 20,000 hours to the project.

But as sometimes happens, restoration threatened to become an end in itself, hence the fretting over wear and tear. The group’s mission statement, in fact, did put bricks and mortar ahead of entertainment. The original mission was “to restore the facility to its 1927 look while being an art and entertainment venue.” That statement “has now been flip-flopped,” according to Burgraff. The current mission is to “provide a historical arts and entertainment center with the purpose of promoting cultural growth and community involvement.”

Burgraff sensed an interest in moving in that direction when he interviewed for the job. “The board members all seemed legitimately excited about making this a performance venue,” he said. He was so enthused by this attitude that he rejected an offer to interview for another position in Madison, Wisc., a job that originally had been his first choice.

Originally from Superior, Wisc., Burgraff was assistant director of operations at the Mayo Civic Center in Rochester when he accepted the Fairmont job. Because he grew up around water, Fairmont’s five lakes were attractive to him, but it was the challenge of the situation which sealed the deal. “It was an opportunity to use my skills to help move this group forward, to put together a subscription series, to make what seemed to be something of a museum into a working performing arts center,” he said.

He developed a subscription system for the opera house, this year selling a package of nine performances for $120. These subscribers nail down 360 seats, leaving just 146 tickets available for the general public for each show. Opera House members, who pay annual dues of $35, get first chance at those 146 remaining seats.

Challenged by the board to innovate a nontraditional event which would interest people who’d never been to the opera house, Burgraff produced a beer-tasting night. “We provided free beer and munchies and sold a commemorative mug for $15,” he said. Held in the Footlight Lounge, the event offered both home brews and commercial beers. It drew 120 people and has become an annual event. Participants taste and rate small samples of beer. “They don’t have a clue as to whether it’s home brew, Schell’s or Sam Adams,” he said. Last year a Fairmont home-brewer won the People’s Choice Award, with a nonalcoholic Sam Adams beer placing second.

Burgraff has a bachelor of fine arts and a master of arts from the University of Wisconsin at Superior and enjoys “being associated with the performing arts. It beats having to work for a living.” He thrives on the job’s variety, “doing budgets, setting up for a lecture series, doing the lights and sound for a show, talking to a service club. There’s something new every single day.” He’s also fascinated by the people he meets and works with, “the people on the board, the people in town, and meeting these performing artists on their way up.”

But when it comes to job satisfaction, nothing beats the combination of children and theatre for Burgraff. “My absolute favorite is when we do student productions and bring the schools in here. We had 1,500 kids come through the door in two days. They saw ‘Lyle the Crocodile,’ and when they walked out, you could see the excitement in their eyes,” he said. “We are building such a future for this place. Every time they come and have a good experience, we know it’s something they’ll want to continue as adults. They’ll be the patrons of our future. We’re setting the foundation for the future.”

In a sense, the opera house’s future is already somewhat secure. Its endowment fund has grown to $560,100 during the past 20 years, and it seems firmly established in a community known for being supportive of the arts. “Fairmont is rich with culture and entertainment,” Burgraff said, almost sounding like a Chamber of Commerce recruiter. “We have the Fairmont Community Concert Assn. and the Civic Summer Theatre. The high school drama department puts on top-quality productions and we have a city band that plays in the park. There are a number of art galleries here too, although they don’t call them art galleries,” he said, referring to art continually on display at banks, the medical clinic and other businesses. “There is truly an abundance of cultural activity here.”

But he cautions that the “arts in themselves are not a money-making venture. This facility has a history of not making money, dating back to the original investors in 1902. We’re in a really tough retail business trying to sell something to people they don’t need.” Although he believes “people who have access to the arts are better off, mentally and sometimes physically, it’s still a tough sell.”

In the five-year vision statement he recently submitted to the board, Burgraff calls for launching a major endowment campaign to raise an additional $350,000, doubling opera house membership to 600, and obtaining grants for special projects.

He also advocates establishing a “brown bag” noon lecture series featuring four regional speakers and one national speaker (such as the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture) every season and adding a youth-family series with two school performances and two evening performances each year.

Burgraff would like to see the opera house merge with Civic Summer Theatre or consider forming a community-based theatre company of its own.

The vision statement also contemplates more and better-trained volunteers and additional paid staff, as well as proper rigging, modern sound and new instrumentation for the stage. Immediately following his itemized list, Burgraff placed a statement designed to challenge: “We should dare to DREAM that WE might make a difference in our community!”

Burgraff, 40, seems content to continue as managing director of the opera house, at least for awhile. “There’s still too much to do here for me to be looking for another job right now.”

He once saw the opportunity he passed up in Madison as a stepping stone to “going back home” to the Duluth-Superior area. “I always loved the big lake.” Now he enjoys paddling his canoe on Fairmont’s lakes and observed that life’s dreams can change. “Moving back home is no longer the most important thing.”

© 2001 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.