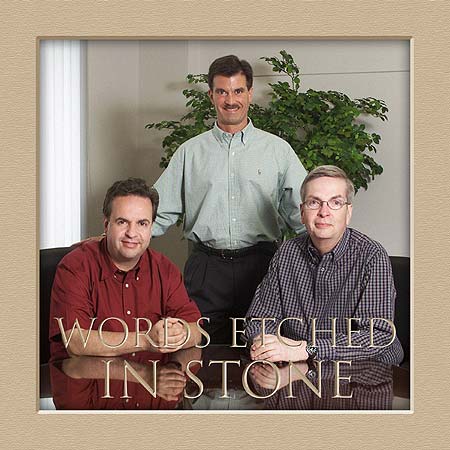

Coughlan Companies

L to R: Bob Coughlan, Joe Hilger and Bill Coughlan

Photo by Jeff Silker

Capstone Press keeps exploding, Mankato may someday be known as the “Book Publishing” Capital of the Upper Midwest.”

You’re excused if you’ve never heard of Capstone Press. New owners coaxed it out of financially troubled obscurity in 1990, re-starting it with two employees and a vision.

It’s hidden away in the former Good Counsel Academy in Mankato, not making much of a footprint on Mankato’s landscape. But it’s become an energized player in children’s educational publishing, spinning off four related enterprises.

From two employees and 48 titles in its first year, the publishing venture now has 136 employees who will market 450 books this year. It has 2,500 active titles in circulation. There’s no timidity about the future. The owners dwell on “looking for new opportunities.” There’s no talk of consolidating gains, no fretting about putting a lid on unmanageable growth.

The money, energy and vision fueling Capstone comes from Mankato’s Coughlan family, an Irish Catholic clan best known for its long association with Mankato-Kasota Stone, Inc.

T.R. Coughlan, great-grandfather of the current Coughlans, bought the quarries in 1885. The family and its quarries are nationally known in the stone industry. Their limestone enhances the durability and appearance of many famous buildings in the U.S. and overseas. (Just to drop an international name, Shanghai Grand Theatre has a feature wall made from Mankato-Kasota stone.)

In the last 20 years, the Coughlans’ holdings have gone from a single company with less than 50 employees to seven with nearly 250. If you’re wondering whether there’s a synergistic relationship between quarrying stone and publishing books, there isn’t. Certainly, prehistoric society’s first written communication may have been pictographs scratched in stone, and God gave the Israelites His 10 commandments carved on stone tablets. But no self-respecting Coughlan would stretch that far to establish a connection between quarrying stone and publishing.

Book publishing is a way of spreading risk, according to two Coughlan brothers who are closely involved in the family’s enterprises. Better yet, they say it’s fun. The Coughlans apparently are carrying on a family tradition of enjoying their work, spreading financial risk and practicing a little philanthropy along the way.

“What we learned from our father is that you can’t be dependent on just one business,” said Bill Coughlan. He is one of seven living siblings in the current Coughlan generation, five of whom are involved in the family’s businesses. In the 1960s, during a downturn in the stone business, the family expanded into banking, starting Valley National Bank in North Mankato and acquiring another bank in Mankato, one in St. James and one in Sherburn.

The Coughlans sold those banks in 1978, but diversified again in 1989, buying Mankato Screw Products. That company provides precision-machined parts to original equipment manufacturers in a variety of industries. In 1990, they diversified further by purchasing Ulmer Pharmacal, a Twin Cities company producing health care products. They sold Pharmacal two years ago.

In 1990, a banker aware of their desire to diversify steered them to Capstone Press.

Capstone’s rapid expansion stretched the family’s management resources and eventually changed the shape of their organization. They began reaching out to recruit top talent. As a first step, they hired Bev Weir, who had been in human resources with another Mankato company. She fine-tuned their human resources function, insuring that their pay and benefits were competitive, and the Coughlans credit her with being a key player in their recruiting efforts.

A few months after Weir joined the company, the Coughlans recruited Joe Hilger, who had been one of Weir’s co-workers. Discussions between Hilger, Weir and the Coughlans led to the formation of Coughlan Companies, Inc. (CCI) as an umbrella organization. It was formed to provide overall direction to the individual companies and administrative services such as accounting, data processing and human resources.

Hilger, who became CCI’s president, said “the key to any business situation is being able to build the right team. It doesn’t really matter what your product or service or industry. If you have a good feel for your customer and your market and you can assemble the right team, you’ll be successful.”

One afternoon in late May, Hilger sat in a large conference room on the second floor of Good Counsel Academy, talking about CCI. With him was Bob Coughlan, CCI’s chief executive officer. “Joe’s done a real nice job of installing talented people in our operating divisions,” Bob remarked. “We spend a lot of money recruiting and advertising. As we’ve become a bigger organization, more well-known, more successful, that brings us a constant supply of inquiries.” Some of CCI’s recruits, like Hilger and Joel Endres, general manager of Mankato Screw Products, came from other Mankato companies. “Getting to know players in the various industries in which we operate also leads CCI to potential candidates,” Bob said.

Although the Coughlans are loyal to their hometown, Mankato’s rural location sometimes is an impediment to recruiting. CCI eliminates that roadblock by “allowing people to operate remotely. They come in as needed. Some have staff here, some elsewhere,” Bob said, pointing out that technology minimizes geographic restraints. For example, the heads of three Capstone spin-offs live far from Mankato. The president of Compass Point Books lived in Rochester, New York, but moved to Chicago recently to open an office. The publisher of Capstone Curriculum lives in Sacramento, Calif., and the managing director of Picture Window Books, originally from Mankato, lives in Minneapolis. Not insisting that key players live in a particular location is an effective recruiting technique, according to Bob.

Bill Coughlan, CCI’s senior vice-president, said the companies have been “lucky at getting good people. They know we’re good employers. They see the quality of our products, the benefits we provide. We’re a family-oriented business.”

Hilger said he saw CCI as “a good opportunity to get in with a growing, dynamic organization.” He felt his background in finance, team-building and developing policies and procedures provided CCI with “things a young, dynamic organization needs to start building infrastructure.”

CCI’s corporate culture is “anything but stagnant. We’re always looking at new things, trying to figure how to do some or all of them,” Hilger said. “We’re aggressive in terms of growth and sales. There are millions of things going all the time. People need to wear a lot of hats, be flexible and agile and go in a lot of directions. We’re young, dynamic and fun. It’s not some stuffy, stoic, hierarchical company.”

Hilger believes “the thing that drives this whole organization is Bob. He’s very entrepreneurial. There’s a constant flow of new ideas, new opportunities.”

CCI is like many other corporations in some respects, according to Hilger. Individual entities, for example, are continually “fighting for the available resources. It’s one of the things that makes my job great, but it’s very wearing at the same time.”

The conference room where Hilger and Coughlan sit on this afternoon sparkles with newness, devoid of dust and corporate clutter. The entire second floor smells of new wood and fresh paint. It’s just been remodeled to convert double dorm rooms, which housed high school girls until the academy closed about 20 years ago, into more office space. Capstone, which started by renting 1,000 square feet at Good Counsel, now leases 30,000.

“We’re building a new distribution center in North Mankato and we could build our headquarters there,” Bob said. “But we like it here. It’s a nice campus atmosphere. Our employees love it because of the very serene environment. It’s surrounded by wildlife, by woods.”

The campus is home to the School Sisters of Notre Dame, a religious order devoted to education. “Capstone is welcome here because we’re in education. Our mission and their mission are consistent,” Hilger said. He notes that Rasmussen Business College is a former tenant and that another small publishing company, AppleTree Press, rents space at Good Counsel.

Bob elaborated on the connection with Good Counsel and Catholic education in general. “Many of our staff and their children were taught by members of this order. Joe’s dad taught at Loyola High School. My brother Bill is on the order’s development advisory board.”

A modest sign on an out-of-the-way building directs visitors to Capstone Press and its subsidiaries where John Coughlan serves as publisher. “John provides the vision for how the products feel and read, what the customer is, the audience we’re going after,” Bob said. “Our in-house people try to get John’s vision into guidelines for our authors.” Although John’s background is in limestone sales, Bob said he “has quite a background in reading” and is something of a medieval history buff.

After acquiring Capstone in December of 1990, the Coughlans finished the firm’s uncompleted books, and then idled the company for a year. “They took a year off to study the market, investigated the niche and possible directions, and then ramped up again in 1992,” Hilger said.

The Coughlans depend on free-lance writers, chosen for their expertise in various topics, to produce the books, following guidelines and specifications set forth by the various publishing companies. In CCI’s lobby, a few of the hardcover books are scattered on a table, colorful and inviting. There’s one called “Hawks.” Another is titled “Animal Ears.” There are books on careers, ranging from “Travel Agent” to “U.S. Army Special Forces.” There are books on geography (“New Hampshire Facts”) and books on character building (“Honesty”).

Bob estimates that 65 percent of the books are sold through distributors, with the balance marketed directly to schools and public libraries. “We try to exploit every channel we can,” he says. “We use a lot of direct mail, we use independent sales representatives, we have an inside sales group that uses the telephone, and we go to many trade shows and conferences.”

The company has no presses, so it relies on printers in North Mankato, Wisconsin and Illinois. The possibility of printing in China is being explored, Bob said. The Coughlans export books in English to South Africa, Australia, Canada, Singapore and a variety of Southeast Asian countries. Some titles are also published in Spanish for distribution in the U.S. and abroad.

When the Coughlans first considered acquiring Capstone, Bob said they had a natural interest in children’s books. “We had young families. The people in our businesses had young families.” They were intrigued by the concept of publishing books for children. “The industry had an appeal to us. The demographics were strong. Most importantly, it was the end customer, the young students. Working with schools and youngsters was a nice way to make a living. It was stimulating, contemplating the opportunity, the market, the end user.”

The reality lived up to what the Coughlans contemplated. “It’s fun to see the growth in a little mind. We deal with kids who are learning to read, some of them struggling in the process,” Bob said. Bill added “our books are also used to assist immigrants who come to our country to learn English and to learn about our culture.”

The foray into books holds a more personal meaning for Bill, because he once had difficulty reading. His parents hired a member of the School Sisters of Notre Dame to tutor him during his sophomore year of high school “because I couldn’t read three words in a row. I didn’t want to.” The tutoring turned him into a rapid reader. “I attribute a lot of my personal success in business to being able to read, so we’ve continued on with trying to help others to read. If people can read and write, their self-esteem goes up significantly.”

After buying Capstone, Bill says “one of the first things we initiated was to give away our books to every school in Mankato.” Now the company donates thousands of books every year, many to inner-city schools across the country. “Learning to read is something we need at all levels in our culture.”

Bill pointed out that the stone company has often contributed limestone for buildings at the University of St. Thomas and the College of St. Catherine in the Twin Cities and to many local institutions, including Bethany Lutheran College, Minnesota State University, Immanuel St. Joseph’s Hospital and the School Sisters of Notre Dame. This is a tradition started by his grandfather, which has been carried on through the years. “All our lives we’ve seen that what we give away keeps coming back. That’s the theory behind corporate philanthropy.”

The Coughlans are pleased about how the publishing business has developed. It’s more than quadrupled since 1996, become “bigger than our original hopes,” Bob said. “We’re surrounded by a wonderful team and extraordinary customers. We’re blessed with a really strong mission.”

Stone Cold Love

Despite the fun and explosive growth it’s enjoying with book publishing, the Coughlan family remains committed to its core businesses of quarrying and manufacturing.

The family formed Coughlan Companies, Inc. (CCI) in 1996 as a holding company for its various operating entities.

The stone company is the oldest business in the group. It’s been operated, either actively or under lease, by four generations of Coughlans. “My father once said anything’s for sale for a price. But it’s been in the family for so long, I don’t think we’d sell it,” said Bill Coughlan, senior vice president of CCI.

Bob Coughlan, CCI’s chief executive officer, agrees. “The stone company is integral to who we are. CCI is organized into two areas, manufacturing and publishing, and we want to see both groups grow.”

Over the years, the Coughlans have developed a personal and professional attachment to the stone business. Bob, active in selling limestone before heading the publishing venture, recalls how he absorbed the history and traditions. “When we were little kids, we traveled with our dad. He pointed out interesting architecture, particularly if it used his stone. He had an interest in the way buildings were designed. He’d talk about it and instilled that sense of heritage in us.”

Bill remembers growing up when the stone company produced cement and powdered lime, two products that have been discontinued. The quarry once turned out cement slab sections for city sidewalks, all imprinted with the name “T.R. Coughlan.” When Bill saw that name on so many sidewalks around Mankato, “I always thought my great-grandfather owned the town.”

Mankato-Kasota Stone plans to open a new quarry soon just north of the Mankato city limits. “That quarry will have stone reserves lasting 40 to 50 years,” said Joe Hilger, president of CCI. “The life expectancy of our present quarries is about 20 years.”

Hilger says the quarries have “typically provided stone for building facades. Now we’re investigating stone for the landscape market. We’re always looking for ways to sell stone. The beauty of it is we can take a lot of the broken pieces or mill ends, do little or nothing with them, and they would be appropriate for landscape applications.”

Although the Coughlans and Hilger say they’re “always looking for new opportunities,” that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re in the acquisition market. “Our basic philosophy is to build rather than buy,” Hilger said. “We feel we can do this successfully over time, without buying an organization and dumping all that debt on top of it. That often kills a start-up.”

Both Mankato Screw Products (MSP) and Mankato-Kasota Stone (MKS) operate with state-of-the-art equipment. MSP, which has attained the ISO 9001 quality rating, furnishes machined parts to original equipment manufacturers. Founded in 1954, it was purchased by the Coughlans in 1989.

MKS is currently involved in attaining the same type of ISO 9001 certification as achieved by MSP. The stone company employs a variety of fabricating and finishing equipment, some computer-operated, to slice and shape limestone for various building applications. Most of it forms facades for buildings, but some is split and used for windowsills, countertops and flooring.

Founder T.R. Coughlan was an Irish immigrant who came to Mankato in 1883, working as a masonry foreman during construction of the Saulpaugh Hotel. In 1885, he bought the quarry property, which contains limestone formed by glacial pressure.

In the company’s early years, nearly all its stone went to railroads for use in everything from bridges to ballast. In the early 1900s, the Coughlans began selling stone for buildings. Now the well-known stone is specified by architects across the U.S. and in some locations overseas as well.

The company’s current sales catalogue shows the stone used in various kinds of buildings across the U.S., from California to Pennsylvania. The catalogue’s cover features La Salle Plaza in Minneapolis. Other Minnesota buildings in the catalogue include Adath Jeshurun Synagogue in Minneapolis, the Minneapolis Post Office, the University of St. Thomas, and the St. Paul Companies.

Also pictured are the Gates Computer Science Center at Stanford University, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jacob’s Field in Cleveland, OH, and Aronoff Center in Cincinnati, OH.

Many of the buildings on the University of St. Thomas campus have facades of Mankato-Kasota stone, some of it contributed by the Coughlan family. That practice began with T. Merritt Coughlan, son of the company’s founder. T. Merritt and several other Coughlans are St. Thomas graduates.

© 2002 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Pingback: Connect Business Magazine » Off-The-Cuff » Changes

Interesting article about your company. It helped fill in some gaps in our family history as my husband’s grandmother was an O’Callahan and

one of her sisters married a Coughlin.

We also run a family business but we are only into the 3rd generation. With examples like yours, I hope we will continue.