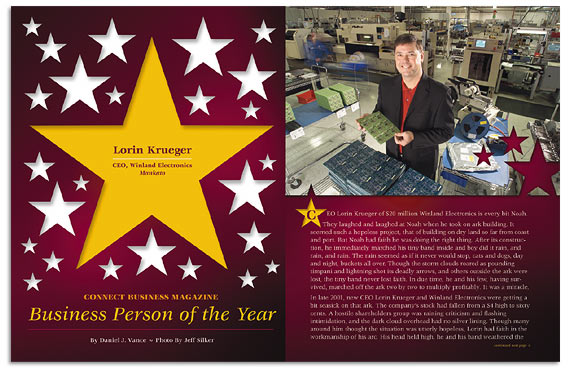

Lorin Krueger – 2004 Business Person Of The Year

By Daniel J. Vance – Photo by Jeff Silker

CEO Lorin Krueger of $20 million Winland Electronics is every bit Noah.

They laughed and laughed at Noah when he took on ark building. It seemed such a hopeless project, that of building on dry land so far from coast and port. But Noah had faith he was doing the right thing. After its construction, he immediately marched his tiny band inside and boy did it rain, and rain, and rain. The rain seemed as if it never would stop, cats and dogs, day and night, buckets all over. Though the storm clouds roared as pounding timpani and lightning shot its deadly arrows, and others outside the ark were lost, the tiny band never lost faith. In due time, he and his few, having survived, marched off the ark two by two to multiply profitably. It was a miracle.

In late 2001, new CEO Lorin Krueger and Winland Electronics were getting a bit seasick on that ark. The company’s stock had fallen from a $4 high to sixty cents. A hostile shareholders group was raining criticism and flashing intimidation, and the dark cloud overhead had no silver lining. Though many around him thought the situation was utterly hopeless, Lorin had faith in the workmanship of his arc. His head held high, he and his band weathered the storm.

Behold! A rainbow suddenly arced across the sky as Winland Electronics posted a modest quarterly profit. It then made money again the next quarter, and the next, and—now seven straight and counting. Just recently the stock was flirting with $6, and Winland Electronics (WEX:AMEX), one of seven publicly traded companies based in our region, had us believing. What remains is the long-term (and equally difficult) task of proving that gross revenues can rise. For Winland Electronics’ remarkable turnaround, the editor chooses CEO Lorin Krueger as Connect Business Magazine Business Person of the Year.

CONNECT: Your background?

KRUEGER: When I graduated from South Central Technical College in 1976, I landed my dream job working in advanced development at E. F. Johnson in Waseca. The company was working on a project you may have heard of—the cellular telephone. The process was going well. Then AT&T and the FCC began having some disagreements over frequency allocations. In short, the project was frozen, and the freeze cascaded through E. F. Johnson. They had to downsize. I was offered a transfer to a citizens band radio plant being built in Clear Lake, Iowa. I’d worked in CB radio my last year of high school and in technical college at Key City Communications, a radio shop in North Mankato. I knew CB radio might not be the best place to be. The Japanese and Taiwanese had come in and were taking a huge market share.

I decided not to take the transfer, and take my chances in the job market. That’s when I ran into my SCTC instructor Denny Siemer. Winland then literally was in the basement of his home on Viking Terrace. Initially, I took a part-time job with them just to get me through. I kept showing up, and they kept promoting me.

CONNECT: And now you’ve gone about as far as you can at Winland Electronics.

KRUEGER: As for title, there isn’t any further to go. But from a company standpoint, there are plenty of challenges and opportunities yet.

CONNECT: I’ve heard you don’t have a four-year college degree. Some top executives without four-year college degrees are very sensitive about that.

KRUEGER: I’m proud of my technical college degree at what was then Mankato Area Vocational Technical Institute. For me, it was the right choice. At Winland, I’ve had the opportunity to work with some fantastic business educators. Early in company history, Clint Kind was our accountant. He also was department chair of Minnesota State’s accounting department. When Kirk Hankins Sr. began interfacing with Winland in 1977 as a consultant, he was teaching management accounting at MSU. Kirk later became CEO and got Winland off the ground. He was an excellent instructor, teaching cost accounting and business management systems.

So I feel I have been tutored by two prominent business educators. And rather than going into debt getting that education, Winland paid me. Denny Siemer was with the business early, and he too was an educator. So I had both a technical and business education.

CONNECT: Given your background, I’m guessing you probably value experience as much as education when hiring or promoting employees?

KRUEGER: With our people, it’s important to continue their education in some form or fashion. Some of our line people don’t have a post-secondary degree, yet many have shown a willingness to move forward by attending learning opportunities we put before them. For myself, I look for experiences to broaden my knowledge. I attend seminars, symposiums, and classes, and am currently attending the strategic coach program and executive leadership program. You never stop learning.

CONNECT: Could you describe step-by-step the attempted takeover of Winland Electronics? When did you first learn something was afoot?

KRUEGER: Let’s step back to 1998. That year the electronics and technology industries were going great guns. Capacity worldwide to build product was being consumed. It was relatively easy to get new business into 1999. Our clients and customers were challenging us to prepare for an onslaught of new designs and projects. We were preparing.

In late 1999, an investor, who is still a shareholder, began accumulating Winland Electronics stock. At roughly the same time, we began seeing a softening in the technology sector, and it appeared that many of our customers’ projects wouldn’t materialize or would be delayed. At the same time, the industry was experiencing components shortages that were constraining production. So we started to cut back on our expenses.

As we moved into 2000, we experienced more of the same. In September 2000, we put out an announcement to warn our shareholders, trying to communicate openly to them that 2000 was not going well. Delays in customer plans and materials for projects in-hand continued to be a problem.

CONNECT: Perhaps some uncertainty over Y2K?

KRUEGER: It was more that the brakes were being applied to the tech sector. One of our customers was providing product to the trucking industry, and we learned that in late 2000 trucks were not hauling as many loads. Trends in the trucking industry are early indicators of future economic growth.

So we cut back more. We reduced staff, and thought the downturn might be another short, 12-week cycle, one we could ride out. After all, there were material shortages and it was still difficult to locate talent, particularly engineers.

In January and February 2000, the employment picture remained the same: it was hard to find talent. Materials were difficult to obtain with long lead times. Then it was like the lights were turned off. We began receiving a massive number of employment applications from engineers. By late April there was a saturation. The industry was witnessing an unbelievable transition. I’ve been in this business since 1976, and never seen such a quick downturn. Companies were now slamming the brakes on orders.

This is when the criticism from Dyna Technology, the outside shareholder, began to intensify. They said we weren’t reacting fast enough to the changing environment, and that we weren’t acting prudently. We had been trying hard to analyze where the market for our products was heading, but these were unprecedented times. Few people in the industry had seen such rapid change.

We continue to cut back further, but the economy was still declining. The pressure kept mounting from Dyna Technology. They were disagreeing with and criticizing management, and doing it without speaking first with management or the board of directors. And all along they were accumulating shares. We considered their actions hostile towards the company. We offered to meet and discuss issues with their representatives. This all has been chronicled by our FCC filings.

We were making changes. But one thing we couldn’t do was make forecasts, forward-looking statements on future results. This is risky for a public company. SEC regulations limit what we can say. For instance, we couldn’t say we were anticipating a significant turnaround.

CONNECT: Yet they were making forward-looking comments about Winland?

KRUEGER: Anyone can set up a soapbox on the corner outside Winland Electronics to shout and criticize. Dyna Technology said things we could not react to because of legal restrictions of what we could say as a public company. Eventually they organized a “shareholder protection committee,” and through it called a shareholders meeting—and legally they could, because they’d accumulated more than 10 percent of our stock—to remove the entire board of directors and replace it with their own. To that date, the people of Dyna Technology had never been in Winland’s building, never spoken with management, never spoken with the board. Their view was from the outside looking in. Dyna Technology, like all other shareholders, had access only to records we had made public.

Removing the board wasn’t necessary. It was doing a good job, and was majority-controlled by outside directors, not insiders. Accusations were made that Mr. Hankins and others had hand-selected the outside directors. In truth, we had selected outside board members based on talent. We had someone with a great financial background, another from investment banking, and two others were Mankato business leaders. When one of the two local business leaders left to become more active in his own business, we brought in someone with a growth background.

The criticism and pressure kept coming. We knew Winland wasn’t that sick. It had a solid foundation. Everyone knew a great deal of change was necessary for the company to grow, and that the change couldn’t be accomplished quickly.

In years prior, Mr. Hankins, our CEO, had discussed with the board his retirement plans. To help ease this shareholder pressure, to Kirk’s credit, he retired. In doing so, he made the motion to name me CEO. But that transition had already started, and was only hastened by the dissident shareholder action. Kirk was a strong individual, and had cared enough about Winland to step aside. Afterwards, we restructured the board. Two of seven directors from the original battle are still with us today. We’ve since downsized the board to five to cut costs, with four board members from outside the company, including the Chair. I’m the only director from inside the company. Our current board has talents in areas where we’ve had weaknesses. As a public company, we have governance needs because of regulations that require the person heading our audit committee to be financially savvy. In our case, that person is a CPA, and a former Chief Financial Officer.

CONNECT: Would the changes at Winland have occurred without Dyna Technology’s intervention?

KRUEGER: The changes would have occurred anyway—and the intervention actually delayed some change. The hostile attempt to overthrow our board cost this company more than $250,000. Everyone inside the company knew we were headed down the right path. Should we have moved quicker? Looking back, perhaps yes. But 99 out of 100 CEOs of technology companies operating the last three years would say that today.

CONNECT: Does Dyna Technology yet own 16 percent?

KRUEGER: Dyna Technology owns 13.7 percent. The 16 percent figure represented the total “shareholder protection committee,” which has disbanded. One former member of that committee, a former President of Hubbard Pet Food, meets with me. He understands where the company is, and has skills in areas I value. He is working cooperatively with us, rather than shouting criticism from afar.

CONNECT: 2000 and 2001 were not good years for you personally. How did you cope with the stress and pressure? If Dyna Technology wins, likely you lose your position at a place where you’ve invested 27 years.

KRUEGER: You’re right, I could have been out of a job. My entire business career has been at Winland. There were days during the takeover attempt when I was involved in areas I didn’t understand. How do you take on a hostile takeover? We could have had a gunslinging match.

We decided to bring out the facts of our strength and direction, unveil the truth, and stand on them. As we achieved success, we had to do a better job of disclosing them. We had to become much more communicative publicly. Because of the local media, the perception in Mankato was that we were sick, embattled, and not going to survive.

Mankato is headquarters for only three good-sized public companies: Winland Electronics, HickoryTech, and Ridley. This likely explains why reporters aren’t that familiar with the regulations and intricacies governing public companies. I received telephone calls from Twin Cities reporters who’d read articles written here and did not understand the slant the stories were taking. The articles written up there were much kinder because they better understood the situation.

Anyone from outside the company can criticize us. But I can’t respond always to them because of Securities and Exchange Commission’s restrictions. When I don’t respond to a question from the media, it appears as if I’m stonewalling. But if I do respond, then I’m putting myself in a position of not having disclosed information fully. The SEC does not consider The Free Press “widely distributed” enough so as to include our full shareholder base. I can’t give comments just to them or any other media around here. I have to step back and first work with our investor relations and legal counsel to make sure we can send out a press release for general distribution. That costs money and takes time. So I either have to comment in a general, short fashion, or just not comment at all. Compare that to someone from outside a public company, who can say anything.

CONNECT: So how did you personally cope with the stress?

KRUEGER: I had great inner peace knowing we were doing the right thing. I brought in outside advisors, who were business “recovery” specialists. They had worked with organizations that specialized in turning around troubled companies. I didn’t want to become one. I also depended on the board for guidance. We encouraged one another. I told employees to focus on business, and that I’d be the one responsible for taking care of outside distractions. We communicated well internally, and worked with our legal counsel and investor relations to disclose what was appropriate.

CONNECT: In other words, rather than be eaten up by stress, you took the approach of one-by-one trying to eliminate the stressors.

KRUEGER: That’s right. Mr. Hankins stepped aside as CEO in May, and I was appointed in June 2001. First and foremost, I had to finish Dyna Technology’s challenge to oust the board. We didn’t have to have an annual meeting that year; I asked for one. It was important for us to get in front of our shareholders at a public meeting in December. It was the right thing to do. And again, we were challenged by Dyna Technology, which this time wanted two board members changed. Again, the shareholders voted it down. Every shareholder had the right to be at that meeting. Anything I said at that meeting was considered “full disclosure.” The annual meeting is the one forum in which I can speak openly.

We set milestones. By the next meeting in July 2002, our shareholders had time to absorb what we had said in December 2001, and we could show them what we had accomplished. We would have been profitable the last quarter of 2001 if it hadn’t been for some tax issues not allowed by the auditors because of sensitivity to what was going on with Enron. The auditing firm was being very conservative. We were already coming out of the worst quarter in company history, caused by slow business and a $250,000-plus shareholder battle.

CONNECT: Your R&D budget is down versus previous years. Are you sacrificing R&D to show short-term profits?

KRUEGER: People thinking that haven’t read our 10-Ks. We did lose some talent in research and development, but the number of projects we had to work on was down. We weren’t receiving new contracts for new projects in any great quantity in 2001 and 2002. We didn’t need as many engineering staff members.

Also, we have reallocated some R&D expenses by moving them to the cost of goods sold. Those costs were supporting the manufacturing of the product anyway. Doing it this way is more in line with what our competitors or “comparables” are doing, such as Pemstar or Celestica. Their financial statement doesn’t show any R&D expenses. We do far more on the “development” than the “research” side.

CONNECT: Describe your management style.

KRUEGER: I let people do the work they were hired to do. I know where my abilities are, and have spent a great deal of time the last two years reflecting on them. I also know I need to surround myself with talent to help build up my weaknesses. So, in short, my style is empowerment. I ask my staff to take the responsibility, accountability, and initiative to move their area forward. I trust them implicitly to make those decisions.

CONNECT: So that makes hiring or promoting the right person that much more important.

KRUEGER: Since 1991, Winland has spent a great deal of time on a process called, “Building highly effective work teams.” Every company employee goes through a 12-hour or longer education process designed to help them learn more about themselves, the culture here, and the role they play. We stopped the process during budget cuts, but have started it again. Most important to that process is learning to communicate with others, recognizing communication styles, and learning how to approach people of different personality types.

For example, we don’t hire persons with a “sales” personality for jobs in meticulous and orderly environments. Many businesspeople have read “Good to Great.” The author urges business executives to make sure they have the right people on the bus and sitting in the right seats.

CONNECT: We hear so much of American manufacturers losing business to Asian companies. You “lost” Johnson Outdoor’s business to China. Yet, on the other hand, you’ve also won business back from Asia.

KRUEGER: The remote control market in TV sets, television set production, computer production—high volume electronics are not built in this country, unless it’s a specialized system. Many companies feel pressure to place product in China because they believe doing it saves money. It truly can reduce their costs if the volumes purchased are high enough, and the company has a strong enough commitment to scheduling and predictability.

Johnson Outdoor believes it can save. They are cost-driven, in a very competitive retail environment where every penny counts. I’m concerned that companies leaving this country aren’t looking at the indirect costs. For instance, they may have the added costs of bringing in extra inventory because of transit issues. And in producing products overseas, you don’t eliminate your American project manager, buyers and many other aspects of product cost.

CONNECT: Sometimes don’t orders from China take six weeks to deliver?

KRUEGER: Six to twelve weeks, and changing the order midstream can be a monumental task. Most companies dealing with Asia have to hold extra inventory as a cushion. As for Johnson Outdoors, I hope they realize savings. The media here played their loss up bigger than I wished. They pitted two local companies against each other, which I didn’t appreciate. We sent out a press release announcing the loss of this business to fulfill our public company disclosure requirements. I had to notify everyone. A private company would never have made such a disclosure. But we had to, and it must have been a slow news day.

As for taking business back from China: Select Comfort had been shipping quantities of a part from China because of the unpredictable nature of business trends. We redesigned and enhanced this part, which allows us to be competitive and reduce their inventory.

In general, as long as we keep our labor below a certain threshold, we can compete with China. If we’re producing highly complex products, we can compete. If a customer has concerns about intellectual property being pirated, we can compete. U.S. manufacturers have to focus on their added-value advantages. “Commodity” products are fast leaving this country.

CONNECT: Will Winland ever declare a dividend? Wouldn’t a dividend make the stock more attractive, driving up the price?

KRUEGER: Given new tax laws, the board has discussed dividends. But we’re more concerned with making the best use of capital. Is it to give cash or stock dividends? At this time, we believe the best use of our money is to grow the company. Since 2001 we’ve grown our earnings, with after-tax profits heading toward all-time highs. But we haven’t grown revenues to the level we’d like. We first need to prove to ourselves, and to the investment community, that we can grow revenues. We want to use any sidelines cash to invest in opportunities.

CONNECT: What is a “Supplier Managed Inventory” program?

KRUEGER: It’s when a supplier physically locates a stock location inside a customer’s facility. We have this type of arrangement with Select Comfort. Now they can change their manufacturing schedule on the turn of a dime. They can go to our secured location, and immediately purchase Winland products that they’d normally have to wait days for by truck or UPS. Business today is all about cash flow and turn. This program allows our customers to have material when they need it, no matter the dynamics of demand.

CONNECT: You’re past chair and current director of what is now Greater Mankato Economic Development Corp., formerly Valley Industrial Development Corp. In late November, Brian Fazio, your executive director, passed away while on vacation in Massachusetts.

KRUEGER: Brian will be greatly missed by the community, friends and family. It was quite a shock to receive that type of a telephone call. He was someone who had such passion and energy for his work, family and community. Brian and I developed a close relationship while working on plans and strategies for GMED. He was fun to work with, and he always challenged your thoughts, always probing deeper. I will miss him.

Electrifying Results

Winland Electronics primarily serves the “electronics manufacturing services” market, offering original equipment manufacturers contract assembly services, such as material procurement, final assembly, kiting and system configuration, testing, warehousing, repair, and new product design and development. The company also designs and manufactures a line of “facilities security systems” to protect buildings against unfavorable temperature, improper humidity, water leakage, and power failures. A line of adjustable speed DC motor controls rounds out its resume.

Bobbers and Work Don’t Mix

Amateur radio became a real passion when I was 13. A teacher at Mankato East had me interested in electronics as a hobby. Eventually, my hobby became my job. When it did, I had to find different outlets. Now, music is one release. I have a lot of technical “junk” I connect my guitar to, and I mix the sounds for our charity band, Roses and Thorns. Fishing used to be an outlet of release, but after Johnson Outdoors became a customer I couldn’t put my hand to a trolling motor or rod without thinking about work. I could no longer fish for an escape. So I told our salespeople, “Don’t ever sell anything to the music industry.” If that happens, I guess I’ll have to take up crocheting or something like it because that has no connection whatsoever to technology. — Lorin Krueger.

Getting To Know You: Lorin Krueger

Born: February 15, 1956.

Education: Mankato East High School, 1974; Mankato Area Technical College, 1976.

Personal: Mitzi; children are Jon, 22 and Emily, 18.

Board involvement: Greater Mankato Economic Development Corp.; South Central Technical College Foundation; Twin Valley Council Boy Scouts of America; South Central Technical College Electronics Advisory Council; Exchange Clubs of America (past local and state president); Family Resource Center (past board member).

Calling All Women And Men

Note this on your calendar: We begin accepting nominations for our next Businessperson of the Year award on Sept. 1, 2004. That person will make our Jan. ‘05 cover. She or he can be anyone from any size business, profit or nonprofit. A peer group will judge. Read the Sept. ‘04 issue for details.

© 2004 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Pingback: Connect Business Magazine » Off-The-Cuff » Off-The-Cuff

Pingback: Connect Business Magazine » Cover Story » John Finke