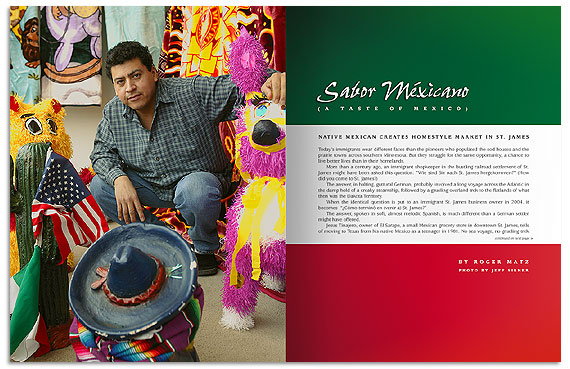

El Sarape

Native Mexican Creates Homestyle Market In St. James

Photos by Jeff Silker

Today’s immigrants wear different faces than the pioneers who populated the sod houses and the prairie towns across southern Minnesota. But they struggle for the same opportunity, a chance to live better lives than in their homelands.

More than a century ago, an immigrant shopkeeper in the bustling railroad settlement of St. James might have been asked this question: “Wie sind Sie nach St. James hergekommen?” (How did you come to St. James?)

The answer, in halting, guttural German, probably involved a long voyage across the Atlantic in the damp hold of a creaky steamship, followed by a grueling overland trek to the flatlands of what then was the Dakota Territory.

When the identical question is put to an immigrant St. James business owner in 2004, it becomes “¿Cómo terminó en (venir a) St. James?”

The answer, spoken in soft, almost melodic Spanish, is much different than a German settler might have offered.

Jesus Tinajero, owner of El Sarape, a small Mexican grocery store in downtown St. James, tells of moving to Texas from his native Mexico as a teenager in 1981. No sea voyage, no grueling trek inland to Dakota Territory.

Nonetheless, Tinajero made a grueling trek of another sort. He trod the hot, dusty laborious path of migrant farm workers, eventually finding his way to the Pacific Northwest where he “picked apples, all kinds of fruit” in Washington orchards. In 1991, he left Washington for a food-processing job in St. James because his wife, Cristina, “had family here.” Now he has an even larger family here, including a daughter Angelica, 12, and a son, Abraham, 7.

Tinajero speaks no English, so his story filters through Eva Esparza, who works in ConAgra Foods’ Human Resources Dept. in St. James where she often translates for the company’s Hispanic employees. Tinajero and Esparza sat in a small booth at the rear of El Sarape, relaying questions and answers across the table in a steady stream of Spanish, with Esparza squeezing the Spanish into English for Connect Business Magazine.

Tinajero, who says he became a U.S. citizen about seven years ago, worked at ConAgra Foods until launching El Sarape in 1997. His motives will not seem foreign to other entrepreneurs. “I like working for myself, with no boss to boss me around. When I have a lot of customers, I feel good.”

He capitalized the venture with $3,000 he’d saved from selling audiotapes of Spanish music, a sideline to his factory job. Tinajero risked his savings because “I was 100 percent sure that it would work.”

El Sarape caters to the Hispanic community, which now makes up about 23 percent of St. James’ population of 4,695. Most of the Hispanics were attracted to St. James by food-processing jobs at Tony Downs Foods and ConAgra Foods. Tinajero stocks the store with Mexican foods, condiments and sauces—canned, packaged, dried and fresh—along with laundry and paper products, candy and video rentals “because I imagined this is what they needed. I tried to bring in everything that Mexicans like and want.”

El Sarape’s appeal goes beyond offering goods that customers once had to travel as far as Minneapolis to buy. “Latin people like coming to a store that has their own culture,” he said.

After two years in his first location, he moved to a larger building on First Avenue South. JC Penney had once occupied that space, but that chain began jerking its stores from small towns in the late 1980s. When he moved into it, the building “had been empty for five years.”

El Sarape stands near the middle of a typical business block, its vinyl banner sign making a definite Hispanic imprint. Next door to the east, running to the corner, is Jake’s Pizza. Next door to the west is Paul’s Pharmacy and Gifts, which also serves as a JC Penney Catalogue outlet. East of that, on the other corner, is Schmidt’s Bakery. Across the street, Tinajero looks out the window at more typical small town businesses—A True Value Hardware and Radio Shack, Dueber’s general merchandise and the Downtown Family Restaurant.

El Sarape stays open longer than most of the neighboring businesses. It operates from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., seven days a week, in the winter. In the summer, it’s open from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. Tinajero doesn’t work all those hours. “I’m here when I am needed,” he said. When he’s not, he has two employees who mind the store. “I can be here all day sometimes and sometimes not at all. But I’m always in communication with the store.” He lives in an upstairs apartment near El Sarape.

No trucks deliver El Sarape’s merchandise because their loads would be too small. “It would be too expensive for them to come here,” he said. Instead, Tinajero makes weekly buying trips to Minneapolis importers and monthly trips to Chicago.

On those trips, he often encounters the owners of other small Mexican stores from around the Midwest. “We stop and talk about ideas, about how you do this or that, but we always make sure we’re not competing with each other,” he said.

Although Tinajero is one of only a few Mexican entrepreneurs in Southern Minnesota, he doesn’t see himself as a pioneer or a leader in the Hispanic community. “I don’t like to talk about myself. I have my work and I like it. I like what I’m doing. I enjoy it.”

Although there are other Mexican stores in Windom and Mankato, Tinajero feels El Sarape is the “best in the area for selection, variety and quality.” Most of his customers come from St. James, but he also draws buyers from Mountain Lake, Butterfield, Madelia and Sleepy Eye and other small towns.

Although he’s expanded once, he’s not sure that will happen again. “If you would have asked me about that two years ago, I would have said I’d like to be twice the size I am now. But I can’t say that now because of the competition,” Tinajero said.

In the past two years, he said the supermarkets in St. James have opened Mexican sections, competing for his customers. Other St. James businesses also are responding to the Hispanic community. (Schmidt’s Bakery has a sign in its window advertising tortillas, for example.)

The rise in competition apparently makes it a struggle for Tinajero to maintain his market share. Rather than consider expanding at this point, he said “I would just like to keep going the way I am right now.” But he’d like to see more Caucasian customers in El Serape. “Very few Caucasians come now and I would like for there to be more. I would like for them to come check out my products. I want them to feel welcome here.”

Although El Sarape devours most of Tinajero’s time, he also runs another part-time business, entertaining as a DJ at Hispanic weddings, anniversaries and other celebrations, traveling as far as Mankato or Estherville, Iowa.

Tinajero enjoys his DJ stints more than El Sarape. When he’s entertaining as a DJ, “I don’t feel like I’m working. I feel like I’m enjoying myself.”

Look both ways before crossing

Railroad officials conceived St. James 134 years ago when they pointed to a spot on a map and said “we’ll make this a division point.”

They selected this spot on the open prairie because it was halfway between Sioux City, Iowa, and St. Paul, Minnesota. The St. Paul and Sioux City Railroad wanted it as a place to repair and provision their passenger and freight trains.

The birthing process didn’t take long and the settlement of St. James blossomed almost immediately. Soon the town had a lumberyard, two hotels, a couple of saloons and stores selling general merchandise, dry goods, drugs, hardware, groceries and provisions. Railroad workers laid 22 miles of track from Lake Crystal to St. James in 1870 and the first passenger train pulled into town Nov. 22, 1870.

Today St. James is better known as a food-processing center, with hundreds of workers employed at Tony Downs Foods and ConAgra Foods. The old St. Paul and Sioux City Railroad disappeared several mergers ago, and the railroad shops are long gone.

Still, motorists must cross four sets of tracks near the food processing plants, where huge yellow diesel engines, now emblazoned “Union Pacific,” idle with a powerful hum as they wait for loads. And St. James still remembers its heritage with a “Railroad Days” celebration every summer.

Stuck in the middle with you

Language formed a barrier between Jesus Tinajero and me as solid as a dam of poured concrete.

Left to ourselves, little or nothing could have passed through, over or around that blockade. But Eva Esparza, an English-speaking Hispanic, served as our conduit. She batted my English and Tinajero’s Spanish back and forth like a linguistic tennis ball.

Esparza works in the ConAgra Foods Human Resources Dept. in St. James and does on-the-job translating for ConAgra production workers, administrative employees and managers. But she’d never translated for a writer and a shopkeeper in a question-and-answer interview session.

That’s a challenging assignment because it involves accurately translating all the subtle nuances embedded in both questions and answers. It required sensitivity and accuracy.

Esparza, a native Texan, was born in Dallas and came to St. James in 1998 for a food processing production job. She’s been an executive administrator in ConAgra’s Human Resources Dept. for more than two years. Some of her work involves translating documents or forms from English into Spanish.

She and her husband, Jesus Esparza, have three children: Priscilla, 11, Patricia, 9, and Jonathon, 5.

Another Hispanic-owned business in St. James

Apolinar (Polo) and Melinda Martinez Sifuentes once ran a mobile grocery service, delivering Mexican foods door-to-door to Hispanics living in southern Minnesota.

Nearly five years ago, one of their customers proposed that they buy his bar in downtown St. James. Since this kind of venture “was completely new to us, we decided to lease it for a year to see if it would be a ‘go’ or not,” Melinda said.

It turned out to be a definite GO, according to Melinda. “We had a good response. People already knew us because we had been delivering groceries in St. James on Saturdays and Madelia on Sundays.”

Now Polo’s Bar is an established fixture of the commercial landscape in St. James and a member of the St. James Chamber of Commerce. Polo’s has developed an appeal that crosses ethnic lines. “At first, our customers were mostly Hispanics. Now it’s almost half and half,” Melinda said.

The bar is about a block east of the town’s only other Hispanic-owned business, Jesus Tinajero’s El Sarape food store. While El Sarape runs 10-12 hours a day, seven days a week, Polo’s Bar is open just on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays. It sells only 3.2 beer, not liquor or wine, and offers snacks like peanuts and popcorn.

Polo and Melinda blended the bar into their schedules, although running the business means a commute from the tiny community of Guckeen, just east of Fairmont. He kept his “day job” as a skilled drywall taper and they continued the mobile grocery business until about a year ago, when Melinda’s mother became ill and needed her care.

Polo does most of the bartending in the 140-seat tavern with the help of their son, Francisco, 21, better known as “Pancho.” Melinda also works at Polo’s, generally on evenings when there’s a band or a special event.

The Sifuentes have brought some extra zest to community life, helping organize an annual celebration on Mexican Independence Day every Sept. 16. The celebration includes contests, dances and displays of arts and crafts in the Community Center parking lot across the street from Polo’s. “We have a parade in the evening, then come back to the parking lot for a dance with a Mexican band,” Melinda said.

She grew up in southern Minnesota and met Polo while visiting her brother in Texas 27 years ago. A native of Mexico, Polo became a drywall contractor in Texas. He continued that trade after they were married and living in Minnesota.

Both speak English and Spanish. Melinda learned her Spanish at home, where her parents generally spoke it rather than English. Her grandparents came here from Mexico many years ago.

While the Sifuentes have become well known in the Hispanic community because of their mobile grocery service and Polo’s Bar, they also are known to a radio audience in southern Minnesota. Every Saturday night Polo and Melinda broadcast an hour-long Spanish music program, taking listener requests for particular numbers. It’s carried on FM 89.7, a Minnesota Public Radio affiliate station in Mankato.

© 2004 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.