Golden Heart Child Care Center

Taylor Corporation owned and operated childcare center serving more than 150 children helps retain female employees and move them into management positions.

Photo by Kris Kathmann

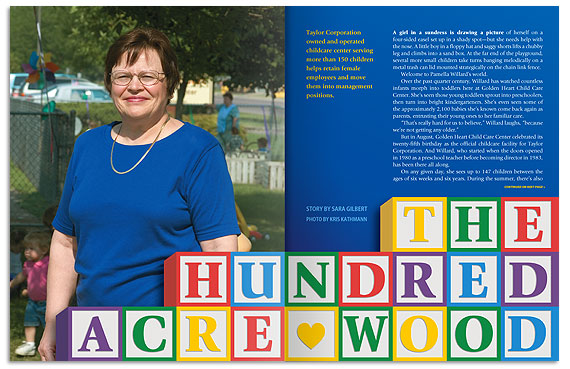

A girl in a sundress is drawing a picture of herself on a four-sided easel set up in a shady spot—but she needs help with the nose. A little boy in a floppy hat and saggy shorts lifts a chubby leg and climbs into a sand box. At the far end of the playground, several more small children take turns banging melodically on a metal trash can lid mounted strategically on the chain link fence.

Welcome to Pamella Willard’s world.

Over the past quarter century, Willard has watched countless infants morph into toddlers here at Golden Heart Child Care Center. She’s seen those young toddlers sprout into preschoolers, then turn into bright kindergarteners. She’s even seen some of the approximately 2,100 babies she’s known come back again as parents, entrusting their young ones to her familiar care.

“That’s really hard for us to believe,” Willard laughs, “because we’re not getting any older.”

But in August, Golden Heart Child Care Center celebrated its twenty-fifth birthday as the official childcare facility for Taylor Corporation. And Willard, who started when the doors opened in 1980 as a preschool teacher before becoming director in 1983, has been there all along.

On any given day, she sees up to 147 children between the ages of six weeks and six years. During the summer, there’s also an additional 60-plus school-aged children who are cared for at an off-site center in lower North Mankato. That’s just a fraction of the more than 300,000 children in Minnesota and more than 20 million children in the nation who attend some sort of childcare while their parents work. But Willard knows almost all the children at Golden Heart by name.

“I try,” she admits. “I enjoy walking around every day and visiting the classrooms. And I still know most of their names.”

Twenty-five years ago, cornfields bordered North Mankato’s Commerce Drive. The Carlson Craft plant, purchased by Taylor Corp. in 1975, was almost alone on an avenue above most of the area’s hustle and bustle. But several hundred employees reported to work up there each day—many of them worried about the children they had deposited elsewhere for the duration of their workday.

One of those was Jean Anderson. In 1979, she was a production employee at Carlson Craft. She was also a mother, struggling to find suitable care for her young children. So she went to her bosses and explained the stress of the situation to them.

“In 1979, employment levels were quite high,” says Larry Taylor, vice president of Taylor Corporation. “But at the same time, there were not a lot of child care centers available. And that made it hard for our employees.”

As one of the managers assigned to look into the problem, Taylor helped research several options, including contracting out for care or paying for childcare at existing centers. But because the business of creating wedding invitations involved several different shifts, such options couldn’t cover all employees.

“At the time, our hours were changing constantly,” Taylor says. “We had people who were part-time and full-time and who worked Saturdays as well. Most centers couldn’t accommodate those schedules.”

It was clear, Taylor says, that the company would be better served by opening a center of its own. Although very few such corporate-owned centers were in operation at the time, the company could see that it would be a benefit to its employees—and to itself as well. So Taylor gathered all the supervisors for a meeting.

“At that meeting, we told them that we understood they were having problems hiring and retaining employees,” Taylor remembers. “We knew that they would sometimes hire employees who wouldn’t be able to work because they couldn’t find child care. So we explained the options we had looked at to them. And we made it very clear that if we built and subsidized a childcare center, that commitment would have to be taken care of before any new equipment could be purchased. It basically came down to playpens or presses.”

They took a vote. And the supervisors overwhelmingly chose playpens.

“It wasn’t unanimous,” Taylor says. “But more than 90 percent were in favor of building the center. So we did.”

Golden Heart Child Care Center opened just adjacent to Carlson Craft on Commerce Drive in August 1980. Between 30 and 40 kids were enrolled in the program. By October, there was a waiting list. Soon, Taylor says, parents were reserving spots 11 months ahead of time. “We had some moms who were coming straight from the doctor’s office to the center,” says Taylor, who has been responsible for overseeing the center since it opened. “They’d come reserve a space before they’d even go home and tell their husbands.”

Taylor Corporation did not open Golden Heart expecting to recoup its costs. There was never an expectation that the center would pay for itself. But the continued investment in the center (the company covers almost half of its ongoing operational costs) has paid off enormously for Taylor Corp. and its employees.

“There are too many variables to actually measure the numbers,” Taylor says. “But in terms of overall employee satisfaction, we definitely think it’s made a difference.”

Since the center opened, Taylor has seen a significant increase in the number of women willing to accept management positions. Jean Anderson, for example, is now a senior vice president. “Once they saw that Golden Heart was dependable and reliable, more women started accepting opportunities to move up,” Taylor reports.

The women who were already in management when Golden Heart opened appreciated the opportunity as well. “There was a group of women who had put off having families because they thought they couldn’t do both,” Taylor remembers. “Suddenly, we had a baby boom; at one time, we had 36 unborn children in our office.”

But it isn’t just the convenience of care that makes Golden Heart appealing to Taylor Corp. employees. Of course they appreciate being able to walk over to nurse their babies or eat lunch with their preschoolers. Of course they’re glad to be just minutes away should their child need them. Of course they welcome the opportunity to stop by for a midday walk or a quick afternoon hug.

On top of all that, however, is the commitment to quality care that has been part of Golden Heart since the very beginning. Much of that, Willard says, is attributable to the staff itself. The child-to-staff ratio, of one adult to three infants, one adult to five toddlers and one adult to eight preschoolers, is better than state standards (comparatively 1 to 4, 7 and 10) and many of those teachers have been around for quite some time. Besides her, four other teachers have put in 25 years; five others have been there for 15 years or more.

“The heart of any center is its staff,” Willard says. “We really care about the quality of our staff and gear into hiring the right people.”

Three of the teachers in the infant room, for example, are registered nurses (“That’s really helpful for all of us,” Willard says). Almost a dozen of the other teachers at the center have four-year degrees in either early childhood or elementary education, and several more have two-year degrees. All of them are required by law to spend two percent of their total working hours on staff development (so 40 hours for a full-time employee), and Willard makes sure they have ample opportunity to do that.

The center closes for a full week at the end of August for in-services, for example. The first Thursday evening of every month is reserved for an all-staff experience, whether in-house or in the community. “We have sessions here on CPR and first aid,” she explains. “We bring in speakers and have video tapes available. We have weekly staff meetings to discuss the various needs of the children. And we always encourage our staff to go to outside conferences as well.”

Willard herself has become an ambassador for early childhood education in general. She’s been an active member of MnBEL, a group of business people committed to the quality of early education for the state’s children. She works with United Way and other community outreach programs. She’s always willing to share what she has learned at Golden Heart with other childcare centers in the area.

And still, she has time each day to walk through the classrooms and visit with the children. Sometimes she sits with them at lunch; sometimes she pitches in on the playground. Occasionally, she welcomes a young charge into her office to “sit and think about life for a while,” she says with a smile.

“To me, it’s very exciting to watch these children develop,” she says. “To see them come in as a six-week-old baby—and then to watch them broadening out, to see their language developing, to see them blossom in so many ways. It’s always amazing to me how fast that happens.”

Ditto for how fast a quarter-century can pass in the company of kids. Willard was looking forward to reconnecting with some of those now-grown children at the twenty-fifth anniversary celebration that took place on August 13. She admits that she likely won’t recognize all of them. And she might not know all of their names at first glance. But she will be delighted to see them again nonetheless. “I’m hoping that a lot of them come to the open house,” she says. “I’d love to see them again.”

In the meantime, she’s happy to spend time with today’s children. They keep her young, she says, and she appreciates that. She likes the view she has on the world and the perspective that the youngsters bring to her life. “Children are children,” she says. “They’re always full of enthusiasm.”

LOTS OF LONGEVITY

Pamella Willard knows that the longevity of the staff at Golden Heart Child Care Center is a bit abnormal. She’s been there for 25 years; so have four other colleagues. Another has put in 24 years.

“That’s pretty unusual in our field,” Willard, the center director, admits.

The difference, she explains, is that employees of Golden Heart are also employees of Taylor Corporation. And as such, they are afforded all the benefits of their coworkers in corporate positions.

“We get all the benefits,” she says. “We have 401(k)s, we get profit sharing, we have health, dental, all of it. In our industry, that doesn’t happen very often. It’s been a great opportunity for me.”

Larry Taylor, a vice president of Taylor Corporation whose responsibilities include oversight of the center, is looking forward to giving out five 25-year pins to Golden Heart employees this fall. He appreciates the consistency of care they’ve been able to offer Taylor Corporation employees. And he knows one of the reasons they stick around so long is the benefits package available to them.

“You don’t see many other child care center employees with profit sharing,” Taylor says. “They get the same benefits as everyone else.”

PARENTAL INPUT

Pam Willard is always open to comments from parents as they come and go throughout the day. But once a month, she sits down with several of them for a formal meeting about the Golden Heart Child Care Center, the children, and the care she can give them.

The 11 members of the Parent Advisory Board, a group of volunteers who commit to two-year terms on the board, meet monthly to discuss concerns, developments, and possibilities for the center. Willard attends the meetings as a non-voting member.

“It’s good for me to have this smaller group to go to and talk about ideas,” Willard says. “I can get feedback on what we’re doing and what we want to do.”

“We really want the parents to consider it their center,” Larry Taylor says. “We want their input on the programs we offer and on what we do with the kids.”

In addition, the Advisory Board puts on Halloween and Easter parties for the children. It hosts an annual parent’s picnic. And it does several fundraising events to raise money for center purchases.

“They gear their purchases toward the children,” Willard says.

One such purchase was the thermostat the staff uses to gauge whether or not the children can play outdoors. Besides telling them the temperature, it also relays the wind chill, which allows the staff to make informed decisions about playtime.

Willard and her staff have greatly appreciated that gift and the many others purchased by the board (including the large indoor climber system for those too-cold or too-hot days), because they are often the items that are hard to fit into the operating budget. They also appreciate the treats board members bring in as a way to thank the staff for taking care of their children. “They do goody days for the staff,” Willard says with a smile. “And we all love that.”

THE PAY OFF

When Larry Taylor tells people about how Golden Heart Child Care Center came to be, the vice president of Taylor Corporation is often asked whether or not the center has paid for itself. The answer, he says, is no. But that’s because it doesn’t have to.

“I ask them, ‘Do vacation days pay for themselves? Do sick days? Does medical insurance pay for itself? How about holidays?’” Taylor asks. “You can’t look at it like that. It’s a benefit; it’s something our employees needed. And so that’s how we have to look at it.”

But like many of the other benefits that Taylor Corporation offers its employees—from a 401(k) plan and medical, dental and life insurance, to profit sharing and product discounts—Golden Heart has been a worthwhile investment.

“It’s an employee benefit, and the company benefits as well,” Taylor says. “We benefit in the employees we can retain. We benefit from the peace of mind those employees have about their children. And we benefit because we are able to have more women in management positions now.”

Even employees who aren’t in a position to benefit from the childcare program are pleased the company offers it. “I’ve never heard a complaint from someone who doesn’t have children and thinks we shouldn’t do this,” Taylor says. “No one has ever complained. In fact, I hear some people saying they wish they were young enough to have more children, just so they could go to Golden Heart.”

© 2005 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Clearly Every day care should have all their employees take CPR and professional rescuer classes.. this could have been stopped.

Mankato Free Press article