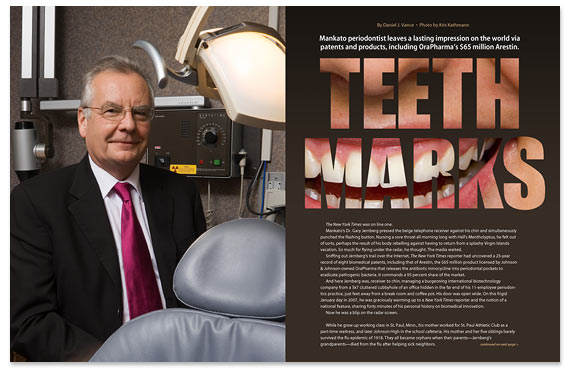

Dr. Gary Jernberg

Mankato periodontist leaves a lasting impression on the world via patents and products, including OraPharma’s $65 million Arestin.

Photo by Kris Kathmann

The New York Times was on line one.

Mankato’s Dr. Gary Jernberg pressed the beige telephone receiver against his chin and simultaneously punched the flashing button. Nursing a sore throat all morning long with Hall’s Mentholyptus, he felt out of sorts, perhaps the result of his body rebelling against having to return from a splashy Virgin Islands vacation. So much for flying under the radar, he thought. The media waited.

Sniffing out Jernberg’s trail over the Internet, The New York Times reporter had uncovered a 25-year record of eight biomedical patents, including that of Arestin, the $65 million product licensed by Johnson & Johnson-owned OraPharma that releases the antibiotic minocycline into periodontal pockets to eradicate pathogenic bacteria. It commands a 95 percent share of the market.

And here Jernberg was, receiver to chin, managing a burgeoning international biotechnology company from a 5×7 cluttered cubbyhole of an office hidden in the far end of his 11-employee periodontics practice, just feet away from a break room and coffee pot. His door was open wide. On this frigid January day in 2007, he was graciously warming up to a New York Times reporter and the notion of a national feature, sharing forty minutes of his personal history on biomedical innovation.

Now he was a blip on the radar screen.

While he grew up working class in St. Paul, Minn., his mother worked for St. Paul Athletic Club as a part-time waitress, and later Johnson High in the school cafeteria. His mother and her five siblings barely survived the flu epidemic of 1918. They all became orphans when their parents—Jernberg’s grandparents—died from the flu after helping sick neighbors.

Jernberg’s father operated a forklift for General Electric in St. Paul. It was a threadbare beginning to life in an inconspicuous home at 761 East Montana, near Lake Phalen, in a St. Paul neighborhood that has since lost its luster.

Besides being an exemplary student, Jernberg grew up a sports fanatic when Johnson High School was a 1960s ice hockey powerhouse. “In fact, I learned to skate before I could walk—almost,” said 59-year-old Jernberg with an amiable grin, sliding another Hall’s Mentholyptus under his tongue. The peppery New York Times interview was fresh on his mind, only hours before, and he was quickly loosening up to this, his second print interview of the day.

He added, “Herb Brooks, who would become the U.S. Olympic hockey coach, was my peewee hockey coach and lived two blocks away. Governor Wendell Anderson lived three blocks away. I often saw them at the ice skating rink in the 1950s.”

Jernberg’s parents hadn’t been to college—his mother not even finishing elementary school—so they were delighted when he earned a four-year scholarship to study chemical engineering at the Univ. of Minnesota. His younger brother Dale also went college.

To earn extra cash, during summers he worked in the porcelain shop at the Whirlpool plant in St. Paul, in 110-degree sweaty heat where “the employees were dropping like flies,” he said. Until age 21 he also sang lead in a touring, regional rock band, The Chambermen, which performed hot pop hits from The Beatles, Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix among others. It was a fun time.

“After finishing my four-year degree, I felt compelled to get a job (rather than continue schooling) because I was living with my parents,” he said of 1969. “I had always been interested in medicine and with helping people, and thought medicine would be a good career. The Univ. of Minnesota had a program in biochemical engineering, a related field, but they had only two openings in the program. Instead I began working for General Mills and was involved right away in designing food processes. It had a new project of manufacturing isolated soy protein and I was involved with a plant start-up in Cedar Rapids, and also with the institutional canning plant next to it.”

Meanwhile, he met the woman who would become his wife, and they married in 1971. Mary Jeanne had started out as a pharmaceutical researcher with the Univ. of Minnesota and later joined 3M, working on drug development projects that grabbed Jernberg’s interest.

Then in 1972, Jernberg took his chemical engineering knowledge to Economics Laboratory, later called Ecolab, and was asked to design a process to manufacture non-phosphate laundry detergent, in part to solve the problem of pollution filtering into and damaging the Great Lakes ecosystem. He and his colleagues developed a unique process of spray-drying chemicals into micro beads, and he gained valuable experience that would steer him later in life with his many biomedical inventions.

Then came change. Try as he could to resist, by 1974 Jernberg’s burning passion for medicine had become an irresistible force. Mary Jeanne was emotionally supportive and earned enough to financially support them both, so he re-entered school, this time the University of Minnesota School of Dentistry.

“It came down to choosing between medical and dental school,” he said. “I decided on the latter because it was more hands-on, and you could own your own practice, be your own boss. And I was interested in that.” He graduated in 1980 in periodontology, and because of family pressure from Mary Jeanne’s parents and his, they decided on settling in Minnesota, and eventually Mankato, which didn’t have a periodontist. While he worked at 99 Navaho Avenue, she stayed home with their two young children.

Said Jernberg: “In dental school I had exposure to the various specialties, and liked periodontics, an emerging field. I liked doing the surgical procedures because they were technically demanding. It’s very rewarding seeing something done and getting instant gratification that you have done a good job. And someone is helped by it.”

A periodontist is someone practicing periodontology, which refers to perio (around) dont (teeth) and ology (the study of). The field deals with diseases of the teeth, and of the structures around the teeth, such as the jawbone, ligaments, and gum tissue. According to Jernberg, periodontal disease is the most common chronic infection known to mankind, the main cause of adults losing teeth, and a risk factor for stroke and heart disease. As for the latter, smoldering chronic infections cause the body to ramp up the immune response, and that continual inflammation can damage various body systems, including the arteries. Periodontal bacteris and their toxins also can invade soft tissue, the blood stream, and arterial walls.

In essence, a periodontist is to a dentist what a cardiologist is to a family physician—a specialist. When beyond treatment by a general dentist, most patients with moderate to advanced periodontal disease are referred to a periodontist for treatment. Jernberg’s office also does dental implants.

He said that periodontal disease begins when specific, pathogenic bacteria forming biofilms negate the body’s self-defense system. “The bacteria have some evolutionary ways of building to a certain mass and turning on virulence genes,” said Jernberg. “Bacteria can actually signal back and forth chemically. We know a lot more about the nature of this infective process now than we did in 1980.”

In 1980, then 33-year-old Jernberg began mining heavily from his chemical engineering background to devise improved treatments for periodontal disease. The ideas just came to him. Knowing the disease arose from bacterial infection, he thought of, well, fighting the infection. Classical periodontics involved the mechanical removal of bacterial deposits from the tooth root surface—and coupling it with an appropriate antibiotic to kill bacteria infecting the adjacent gum tissue ought to improve outcomes, he surmised.

He remembered his work with Ecolabs and of his knowledge of embedding a drug and having it gently release from within a micro-particle. As for periodontal disease, he invented a delivery system that would deliver an antibiotic exactly where it was needed, at the right dosage, and sustain the release, rather than needlessly “marinating” the entire patient with the antibiotic. It was ultimately shown through research that systemic dosing, i.e., swallowing antibiotic pills, did not deliver a sufficient antibiotic concentration throughout the infection site to kill the biofilm.

However, the micro-particle embedded antibiotic could kill the bacteria biofilm, and after that the next generation of bacteria amazingly were less pathogenic. In other words, Jernberg’s singular invention had the potential to create a healthier mouth “ecosystem.”

Soon after having his first patent issued with the aid of Merchant & Gould, Minneapolis patent attorneys, he received three telephone calls: the first from a California CEO, the second from a oral care company VP, and the third from a small start-up. He knew he had something very special, and negotiated the best deal, signing a license with the major U.S. oral care manufacturer to develop a product. When the manufacturer failed to meet certain “milestone” arrangements in the agreement within five years, Jernberg “re-released” the product for development to a division of American Cyanamid, Lederle Labs. That company spun off his invention to form another company, which only recently was bought out by Johnson & Johnson.

Twenty-one years after the original idea, and after $100 million had been spent developing it, the Food and Drug Administration finally approved Arestin for sale. In 2006, the product earned more than $65 million in sales (with a projected 20-25 percent annual growth rate), and Jernberg earned royalties on each one. The product releases the broad-spectrum antibiotic minocycline into a periodontal pocket to clear out pathogenic bacteria. His was a successful introduction into the field and would whet his appetite for more patents and more products.

“I thought the whole process was fun and challenging,” Jernberg said of inventing and bringing a breakthrough medical product to market. “It was like fishing the first time and catching a big fish. So what do you want to do? You want to fish again. So I did it again, and have done it eight times total, with eight patents ranging in applications from drug delivery to tissue regeneration. I am using my training in chemical engineering to be a problem solver.”

Of the latest patents, all seem to have great potential. The idea for one came about after his mother had several heart attacks and required quadruple bypass heart surgery. So he invented a way of releasing drugs and enhancing their cellular uptake from cardiac stents to improve on the current system using certain polymers that seem to cause arterial late-stage blood clots. A major stent manufacturer has licensed the patent.

Another of his patents has been licensed to a prominent company manufacturing coronary artery grafts made from synthetics.

“Out of the eight patents, I have six licensed,” said Jernberg. “My patent attorney says that’s unbelievable—that I am the most successful inventor he knows. You can get a patent, but to get someone to spend $100 million developing it, that’s another story.”

He and an Arizona dental school dean have a ninth patent in the works involving a delivery scheme able to repel bacteria from dental material. They have signed an agreement with an Australian company owning proprietary molecules, and should be able to license their intellectual property to an appropriate bidder in the dental manufacturing field. The product could have numerous revolutionary medical applications, including some involving the use of urinary catheters and prosthetic devises, and even for the treatment of cystic fibrosis and pneumonia. The Centers for Disease Control report that biofilm infections account for 40 percent of all infections, said Jernberg.

“I especially enjoy the hunt,” he said of the intensive and ongoing effort getting his patents licensed with manufacturers. By this point in the interview he had settled in. His voice raspy from hours talking with two interviewers, he still had plenty of physical energy left. He sipped steaming hot decaffeinated tea. Pointing to a spot on the break room table, he kept on: “You have this piece of paper, this patent, but getting that was never my point. The point has been to do something with it. You don’t only want to get up to the plate, you want to hit the ball, too.”

Usually he visits manufacturers himself rather than the other way around, a personal approach to selling his patents to potential suitors. The Lederle Labs spin-off expended more than $100 million in resources bringing Arestin to market, and many of Jernberg’s other patents (and products) might cost another company more. A lot rides with each presentation.

“I have been surprised a lot of people have been able to recognize my name,” he said of making sales presentations to companies around the globe. “They network and get to know who you are that way. Being recognized humbles me. The last thing I want to be is arrogant or cocky because it can ruin you.”

The process of just selling an idea can take years, especially when dealing with corporations with layers upon layers of staff—and the Food and Drug Administration and its seemingly endless number of hoops to jump through. Think of it: Arestin was an idea in 1980, fully patented in 1987, and became a marketable product in 2001—21 years. The product was developed by two different companies, and survived meticulous FDA animal, human, lab, safety and toxicity studies.

“The odds on the FDA approving a new compound are one in five thousand,” said Jernberg, “which are about the same odds as making a hole-in-one on a par-three golf hole. Fortunately, my innovation was used along with a generic antibiotic, minocycline, which had already been approved. That greatly improved the odds.”

Arestin will be marketed in Europe and Japan soon as the product bounds over numerous regulatory hurdles there.

Said Jernberg, “It’s fun at each stage of the game even though not everything will turn into a product.”

He said his ideas just come to him when he’s alone—often when Mary Jeanne is off managing her separate businesses, which include Dairy Queen, Karmelkorn, and Orange Julius franchises in St. Cloud, and Subway franchises in Rochester. She earned an MBA from Minnesota State University years ago and was a professor. He rests on the couch, relaxed, and begins the biomedical inventing process by harvesting from his chemical engineering background and vast knowledge from being a voracious reader. And he has been careful to observe the world around him.

“I will just sit on the couch and scrawl away,” he said of creating ideas. “Also, we own a condo in the Virgin Islands. I’m sitting there on the beach without a responsibility in the world and all of a sudden ideas start popping into my head. I get a few projects for the year that way.”

Oh does he make inventing sound easy.

“A lot of innovations come from thinking outside the box,” he said. “For instance, an English chemist was walking his cocker spaniel one day when his dog became full of burrs. He had a difficult time getting those burrs off his dog. From that experience he invented Velcro. If you have an interest and keep your eyes and mind open. Some people say these ideas for inventions aren’t obvious, but they are to me. It’s like playing chess. You just need to think a couple of steps ahead.”

Perhaps The New York Times reporter was most surprised by Jernberg’s enduring enthusiasm for seeing his regular periodontal patients. It certainly surprised the Connect Business Magazine writer. Dr. Jernberg has maintained roughly the same rented office space at 99 Navaho Avenue since 1980, and the same 5×7 cluttered cubbyhole of a personal office, and the same breadbox of a break room. He and partner Dr. J. Paul Foster manage a huge load of periodontal patients. No doubt many people familiar with his background and life have seriously wondered—with eight patents, six licensing agreements, and impressive financial success with Arestin, for example—why Jernberg just doesn’t jettison his periodontics practice and devote his professional time and financial resources to dreaming up these revolutionary ideas.

The answer might surprise. “I have the best of both worlds in my careers,” he said. “I can do these highly disciplined surgical treatments and get immediate satisfaction, and on the other hand I can try solving problems that may take years and years to develop. With my career, I am able to balance the two, and not get frustrated too much with one or the other. I love both of them. I am going to keep going this way.”

As for The New York Times reporter: He said he might fly out to Mankato for a follow-up visit one day soon.

Herb Brooks

Former Olympic coach Herb Brooks was also my peewee hockey coach in the 1950s—and we played outside at Phalen Golf Course. One day about ten degrees below zero, we were playing hockey outside. I was about age 10. I was checked hard and lost my glove, and the first thing I did was skate for the glove. When I came back off my shift, Herb chewed me out, saying, “Go for the puck, not the glove.” —Dr. Gary Jernberg.

Super Partner

“My wife enjoyed the pharmaceutical industry, but there was nothing in Mankato for her when we moved here in 1980,” said Dr. Gary Jernberg of wife Mary Jeanne, who had been a pharmaceutical researcher for the Univ. of Minnesota and 3M.

“Then in time, my wife wanted to work as well,” he said. “She bought the Karmelkorn and Orange Julius store when River Hills Mall opened, so when the kids were in college we could have a steady stream of income and have them work there. They could get a good work ethic from it as well.”

She eventually would sell those franchises to Jim and Judy Long of Knight’s Chamber in River Hills Mall. Owning other franchises in St. Cloud, she also helped her son Michael head operations at new Subway franchises in Rochester and ultimately form his own corporation.

Jernberg said, “I respect everything about my wife. She is energetic, has a passion for life, is fun, bright—I could go on and on about her. She is a super partner and soul mate. She has her own interests, and is an independent person.”

The Hunt

Jernberg stated that a new biomedical product easily could take up to ten years to proceed from idea to FDA approval. Some new products or compounds cost more than $1 billion to develop.

“People complain about the high cost of drugs, but not when the drug saves a life,” he said. “Using a previously approved antibiotic and only putting in a new delivery system cost more than $100 million to bring Arestin to market. That’s why I didn’t start my own company. To get someone to license the patent and commit that amount of money is a much tougher deal than getting a patent. That’s the hunt.”

He believed that if the federal government were to step in and further regulate drug companies and pricing, the United States would see far fewer breakthrough innovations such as Arestin, which have the potential to save a great many lives—and healthcare dollars.

© 2007 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.