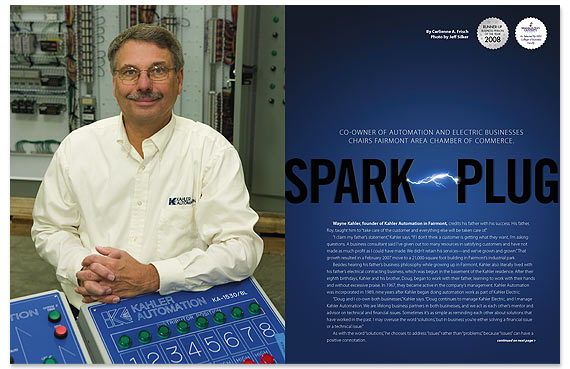

Wayne Kahler – Runner-Up – 2008 Business Person Of The Year

Co-owner of automation and electric businesses chairs Fairmont Area Chamber of Commerce.

Photo by Jeff Silker

Wayne Kahler, founder of Kahler Automation in Fairmont, credits his father with his success. His father, Roy, taught him to “take care of the customer and everything else will be taken care of.”

“I claim my father’s statement,” Kahler says. “If I don’t think a customer is getting what they want, I’m asking questions. A business consultant said I’ve given out too many resources in satisfying customers and have not made as much profit as I could have made. We didn’t retain his services—and we’ve grown and grown.” That growth resulted in a February 2007 move to a 21,000-square foot building in Fairmont’s industrial park.

Besides hearing his father’s business philosophy while growing up in Fairmont, Kahler also literally lived with his father’s electrical contracting business, which was begun in the basement of the Kahler residence. After their eighth birthdays, Kahler and his brother, Doug, began to work with their father, learning to work with their hands and without excessive praise. In 1967, they became active in the company’s management. Kahler Automation was incorporated in 1989, nine years after Kahler began doing automation work as part of Kahler Electric.

“Doug and I co-own both businesses,” Kahler says. “Doug continues to manage Kahler Electric, and I manage Kahler Automation. We are lifelong business partners in both businesses, and we act as each other’s mentor and advisor on technical and financial issues. Sometimes it’s as simple as reminding each other about solutions that have worked in the past. I may overuse the word ‘solutions,’ but in business you’re either solving a financial issue or a technical issue.”

As with the word “solutions,” he chooses to address “issues” rather than “problems,” because “issues” can have a positive connotation.

Kahler’s talent for using words doesn’t necessarily reflect the interests he had in school.

“My least favorite subject was English, but I think that was a little bit of my own attitude,” he admits. “I thought, ‘I’m going to be an electrician; I don’t need to write book reports.’” (Kahler passed the test to obtain an electrician journeyman’s license at age 16. The required age now is 18.) He enjoyed science but originally struggled with math.

“I credit my high school math teacher, Mr. Lou Gerteen, with turning that around,” Kahler says. “He taught math in an enthusiastic way I understood.”

After graduating from Fairmont High School in 1962, Kahler took classes at Northwest Electronics (now part of Brown Institute) in the Twin Cities, working toward certification as a computer engineer servicing large computer equipment. When his father needed surgery three months before Kahler completed the program, he returned home.

“Once I got back to earning electrician’s wages and was back in my element, I decided not to go back to school and finish,” he explains. “But after I had the electronics training, I did more interesting electrical projects, bought technical manuals to read and began attending manufacturers’ seminars, and still do.”

While at Northwest Electronics, Kahler worked at Control Data Corporation, assembling and testing equipment, then for another company that made cables. Later, he was a Univac engineer’s assistant, where he worked on the Nike-Zeus missile guidance system, taking engineers’ ideas and putting them into a formula for a computer to run to see if they would work. For Kahler, studying equals experimenting. He taught himself to write computer code by ordering a computer from Radio Shack and reading instruction books.

Although caught from his father—(“You will pay your bills on time”), Kahler’s business acumen was developed through trial and error. “There were times Doug and I asked ‘Where did we get Business 101 class?’” Kahler says. “We learned by trial and error, nothing that was fatal. I’ve tried reading books on business, but have not found them to be beneficial. I think taking business classes would have been beneficial if time had allowed.”

Kahler describes himself as conservative, an attribute in keeping a company in black ink. “I’m the guy who makes sure the financial condition of the company is sound,” he says. “I’m constantly monitoring sales, shipments, billings and collections. I try to keep in balance the ratios of accounts receivable to inventory or money borrowed. There are basic rules of thumb.”

Again, Kahler is self-taught. He explains, “I mainly picked up on what bankers look for and came up with my own ratios because in some ways it’s the same as electrical contracting, but the manufacturing side causes a different way of analyzing.”

Sitting in the Kahler Automation conference room, Kahler points out the framed batik his wife, Char, created of a Native American chief, which also graced the wall of the conference room in the previous 9,100-square foot building.

“We couldn’t expand our plant, and now we have more space to build and put together our projects,” Kahler explains. “Each person now has his or her own office.”

Kahler’s employees are second in importance only to the company’s customers. Of the eight people who moved with their employer from Kahler Electric to Kahler Automation in 1989, five still work for the company.

“I have a long-term co-worker, Bruce Gemmill, who has been with us over 30 years,” Kahler says. “He’s a master electrician (like me), an electrical engineer and our vice president of engineering. He has certainly been a positive part of our success. We have 33 employees, which includes electrical and mechanical engineers, project engineers who write software for industrial computers (also known as programmable logic control or PLC) and technicians who provide phone support or field service if required. My son, Logan, is VP of Product Development and supervises a team of software programmers.”

Ten employees in production assemble the hardware, including electronics, electrical, pumps, valves, pneumatics or hydraulics. Anything used in industry can be assembled there. Kahler Automation serves a variety of customers with computer software that monitors and accesses their inputs and outcomes. (See sidebar “Nuts & Bolts.”) The company has installed software in more than 1,000 fertilizer/herbicide sites, many of which continue to have work done. Over the past few years, about 70 ethanol plants have been added to the hundreds of industrial customers.

“For an ethanol plant we provide the controls that receive the grain and route it to the point of grind, then route the dry, distilled grain out to trucks or rail cars via electronic scales,” Kahler explains. “The controls are an industrial computer programmed with industrial language. We also collect data in the same system about what came in and what went out—and provide it to the customer.”

“Collecting information for the customer is an important part of all of our work,” Kahler says. “It’s not about the customer punching out more widgets, but it’s what materials are going into the widgets, how long it takes to make a widget and is the machine or the person doing the job well. A customer may use the information to change the process. There’s a trend for having fewer people employed in an agriculture service or a grain elevator and using more unattended systems. Because we manufacture the equipment, it drives us to develop more unattended systems to dispense fertilizers, herbicides and seeds.”

When Kahler began doing automation work, he had to make cold calls to potential customers, a challenging prospect at the time.

“I wanted to get away from agriculture, which was in a downturn, but that’s where the network led us,” Kahler says. “When we started, I expected to do very small projects, but we quickly found ourselves doing computer controls for large plants. My business plan turned out differently.

“Occasionally I still make cold calls, but now it’s not as terrifying. Now, it’s more, ‘I wonder what they do there.’” He researches companies, analyzes how Kahler Automation could help them become more efficient and prepares a proposal.

The plant usually runs from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., with Kahler there before and after plant hours. He also comes in Saturday mornings.

“No day is typical, but I start by reading the local paper and having a cup of coffee,” he says. After responding to e-mails, he checks industrial control equipment available on e-Bay. (“I’m always looking for equipment my customers can use, and I sell some, too.”) Around 8 a.m., he begins calling customers about a project meeting or whether to send out a project engineer to work on a solution. (“It takes me time to get to the root of a problem.”) From 10 a.m. to noon, Kahler meets with various company departments, with overlap among them. (“People come in and switch hats as needed.”) “I take a noon break for an hour and get away with Bruce or Logan for lunch,” Kahler says. “We try to talk about something other than business, but that doesn’t always work. We sometimes talk about solutions.”

Kahler spends afternoons working on project proposals for potential customers and reviewing proposals written by others for accuracy and pricing. (“I give mine for others to review.”) If a customer has an issue, Kahler meets with employees to decide whom to send to the customer. Throughout the day, phone calls keep the routine from becoming—well, too routine.

There also are the days Kahler goes on the road or is airborne in his private plane. He has customers in Florida, Texas, California and New York, but most are in seventeen, primarily agricultural states. Kahler cannot predict how long a trip will take because he often stops to see customers along the way to or from his appointment.

“I used to go overnight, but now I’m home nights because with the company airplane, a trip to southern Illinois and back can be done in one day,” Kahler says. “The plane has helped reduce overnight stays.” (See sidebar “Wild Blue Yonder.”)

Kahler believes his company is unusual in that it’s located in a town of 11,500 people, whereas most of its competition is located in bigger cities. His commitment to his community has kept him there.

“Iowa and South Dakota compete with Minnesota’s industries in our part of the state,” Kahler says. “Iowa offers some very attractive incentives. I stayed in Fairmont because I believe in Fairmont, but the state of Minnesota needs to change its business climate in outstate areas.”

Kahler’s commitment to Fairmont includes chairing the Fairmont Area Chamber of Commerce.

“I bring a view from the manufacturing community,” Kahler says. “The Chamber of Commerce is one avenue of knowing what’s happening and helping to change the direction the community is going, and you’re typically with a group of positive-thinking people. A week-long Blandin Leadership Foundation course changed my attitude from ‘they should fix this street’ to ‘how are we going to make this happen?’”

Even on less than stellar days, Kahler has no doubts about his business choice or his decision to stay in Fairmont.

“I was struggling with a machine about 15 years ago when a friend came in,” Kahler recalls. “I said I was having a hard time solving the problem. He asked if I weren’t doing this, what I would be doing. I said, ‘Looking for a deal like this.’ I’ve wanted to do something like this since I was ten years old.”

[Freelance writer Carlienne A. Frisch lives in Mankato.]

Nuts & Bolts

Kahler Automation is an experienced integrator of custom-designed industrial control systems. Kahler has performed projects for customers such as food processing plants, biofuel projects, metalworking plants and underground mining, to name a few. Kahler engineers incorporate machine control systems with data collection and deliver the data to the front office for use by management in a variety of industries.

For agricultural co-ops and chemical dealers, the company provides a standard line of chemical and fertilizer dispensing equipment, designed to automate chemical weighing, liquid fertilizer measuring, liquid fertilizer blending and dry fertilizer tower control.

Electrical contractors look to Kahler Automation for a line of products that includes electrical disconnects for power on electric motors.

Motor control centers are used in everything from waste water treatment facilities to grain augers on farms. Farmers also look to Kahler for controls that provide automated drying, cooling, filling and dumping based on user-defined temperatures and moisture settings.

Wild Blue Yonder

When operating the controls of his Kitfox aircraft on his way to an Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) fly-in, Wayne Kahler is still pursuing his desire to learn.

“I’m an EAA member who likes to go to a fly-in to see how people are building their planes,” Kahler explains. “Due to my having very little free time, another person built mine. It’s a two-place (two-seater), similar to a Piper Cub. My business aircraft is a four-place Piper Dakota,” which he uses to fly himself and key employees to meet with customers in other states.

Kahler earned his pilot’s license at Fairmont Airport at age 18. Although he can fly the Piper Dakota, he hires a pilot for business trips because he wants to be able to focus on a proposal, issue or sales presentation. He keeps the Dakota at Fairmont Airport and the Kitfox in a hangar on his acreage three miles from Fairmont, where he has a small airstrip. Every summer he attends several Southern Minnesota fly-in breakfasts as well the EAA fly-in at Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

Kahler On Kahler

What’s in a Name? Wayne Kahler has no connection to the Kahler hotel industry in southeastern Minnesota. In fact, when he attended a meeting at the Kahler Grand Hotel in Rochester, he got lost in the basement. A person looking for the front desk saw Kahler’s name tag, asked him for directions and was disbelieving when Kahler could not help him.

Family: A brother, Doug, who is four years younger; wife, Char, an artist in various mediums, such as batik and stained glass, and two adult children. Daughter Chantill is a civil engineer with a professional license who works with water quality and preservation of wetlands. Son Logan, a computer engineer, works for his father.

Politics: “I’ve never gotten involved. My wife was a Martin County commissioner for about eight years, though.”

Hobbies: “I enjoy taking care of 11 acres, which includes a grass airstrip. We’ve turned much of the land back to natural prairie.”

Goals: “I could say that I’d like more personal time, but I have control of that, so it’s self-inflicted. I do enjoy the challenges.”

© 2008 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Good article Wayne. Makes me proud to have spent time working with you in years past. I wouldn’t have minded some overnight trips to IL instead of the long week bouts. Take care and many more successes to you and your company.