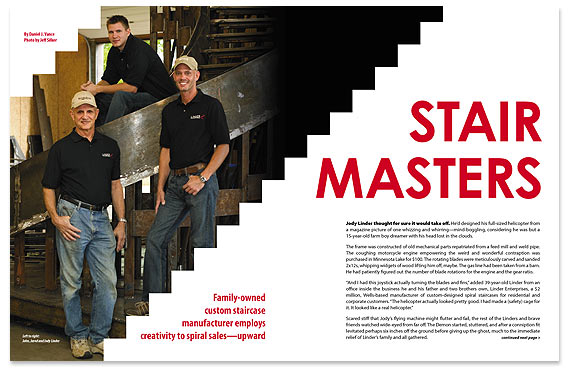

Linder Enterprises

Family-owned custom staircase manufacturer employs creativity to spiral sales—upward

Photo By Jeff Silker

Jody Linder thought for sure it would take off. He’d designed his full-sized helicopter from a magazine picture of one whizzing and whirring—mind-boggling, considering he was but a 15-year-old farm boy dreamer with his head lost in the clouds.

The frame was constructed of old mechanical parts repatriated from a feed mill and weld pipe. The coughing motorcycle engine empowering the weird and wonderful contraption was purchased in Minnesota Lake for $100. The rotating blades were meticulously carved and sanded 2x12s, whipping widgets of wood lifting him off, maybe. The gas line had been taken from a barn. He had patiently figured out the number of blade rotations for the engine and the gear ratio.

“And I had this joystick actually turning the blades and fins,” added 39-year-old Linder from an office inside the business he and his father and two brothers own, Linder Enterprises, a $2 million, Wells-based manufacturer of custom-designed spiral staircases for residential and corporate customers. “The helicopter actually looked pretty good. I had made a (safety) cage for it. It looked like a real helicopter.”

Scared stiff that Jody’s flying machine might flutter and fail, the rest of the Linders and brave friends watched wide-eyed from far off. The Demon started, stuttered, and after a conniption fit levitated perhaps six inches off the ground before giving up the ghost, much to the immediate relief of Linder’s family and all gathered.

Jody hasn’t been the only inquisitive Linder. Brothers Josh and Jared from scratch used to build go-karts, mini-bikes, sleds, motorcycles, television stands, shelving—you name it. (All Linder first names start with “J”, including sisters Jena and Julie.) They all grew up curious and countrified on a Wells row-crop and livestock farm where “you fixed a lot of things yourself,” said Linder. From an early age, the Linder boys learned welding and other skills from their father, John, who owned an army of metal/woodworking tools—and had the temperament and innate ability to teach their use.

“All us boys built things,” said Jody, today 39. His brothers Josh and Jared are 30 and 25, respectively, and John is 66. “If you wanted something, you just found some old weld pipe and built it.”

The Linder family trait of self-sufficiency carried over to homebuilding. In the late 1980s, Jody and John began building John’s new home from scratch, and Dad wanted it to have a distinctive feature. (Josh and Jared were too young to help much.) So they designed a freestanding spiral metal staircase, one that would be embedded in five feet of concrete and would corkscrew up using steel plate to a metal landing. The Linders custom manufactured the railing. Jones Metal of Mankato supplied the spiral beam.

“People coming in (to the home) would say how unique the staircase was,” said Linder of the recurring oohs and ahhs. “And then they would say we should make more of these staircases and sell them.”

They tried. Naturally self-sufficient, Jody and John produced and mailed a thousand brochures advertising their showcase staircase, which they figured could be mass produced for a $20,000 retail price. Astonished, they received back nearly a hundred inquiries, yet none of them culminated in a sale. Only years later did they realize their mistake. They had been advertising a one-size-fits-all staircase to high-end customers interested only in a custom-made product.

Frustrated but not beaten, the Linders instead began building new homes and fixing up older ones for immediate turnaround sale. Yet the idea of manufacturing spiral staircases kept festering on their speaking lips, like a cold sore.

“We decided to try again in the late 1990s,” said Linder. “This time we thought we had a better idea of what people wanted. We made a more economical-type staircase. It was an adjustable one built in sections, erected using bolts, one that could be carried through the front door. That meant it could be placed inside an existing home. That was pretty much unheard of for a freestanding spiral staircase. We called it a modular spiral staircase.” Unlike most spiral staircases, theirs did not have a weight-bearing center pole.

This time, the Linders, now with Josh and Jared, advertised their helical creation in Architectural Record magazine, updated their brochures, and started a website. Said Linder, “Just like on the farm, we were doing most of the marketing ourselves. And we did it well enough to get our first customer. If we didn’t know how to do something, such as digital photography, we just winged it. We set up our own email addresses and registered our own domain name.”

In 2000, their shoot-from-the-hip effort finally hit bullseye: an architect designing a new University of Minnesota-Duluth building read a Linder Enterprises brochure and hired the Wells firm to custom manufacture a two-story spiral staircase. It would be their only advertising success, but was more than enough to pad a weak resume and pay some bills. It took almost a year to build the staircase, so paying for the steel required upfront, short-term financial assistance from Mike Rasmussen of Valley Bank in Minnesota Lake. It also took engineering expertise from I&S Engineers & Architects in order for the state to approve the project.

This time the Linders finally got it: potential customers weren’t looking for one-size-fits-all staircases—only custom-made. In fact, to this day, the Linders haven’t received a single inquiry from anyone about their “standard” model. Being a “custom” company has been a blessing in more ways than one. If they had been mass producing their spiral staircases, a Chinese company by now surely would have copied the design and could have seriously undercut the price, perhaps even below their original $20,000 estimate.

Instead, the Linders sold their first custom staircase for $125,000. “After that project, business really took off,” said Linder of the Duluth building. “We added pictures of the Duluth staircase to our website and designed a new eight-page brochure.” The company painfully learned several lessons while working out its first project, especially ones involving contracts. They built up a database by doing their own Internet searches, and eventually mailed out another brochure. The result was almost 400 inquiries this time. They were off and flying high.

Including its first job, Linder Enterprises has manufactured and installed about 20 spiral staircases ranging in price from $85,000 to $489,000. Almost all their sales leads have originated from their website. A number of other U.S. companies also manufacture spiral staircases, but only a handful, like Linder Enterprises, feature them without center poles. No Linder Enterprises spiral staircases has a center pole—they are free-standing only. It’s purely an issue of aesthetics. And their staircases are strong enough to be stacked on top of each other, sometimes winding several stories high.

As for engineering services, Linder said, “It’s one thing being a welder and another making sure the load will stay standing. Even today, we’re always asking I&S, How light can we make it and yet keep it sturdy, so it doesn’t vibrate? That’s where engineering comes into play. I&S draws up our plans, and the plans go to the general contractor, who approves them. We worked with I&S for months to get the first staircase done. We also regularly use I&S to draw up visuals for potential customers.”

Though naturally self-sufficient, the Linders haven’t had the specialized degrees, know-how or heavy equipment to perform certain business or manufacturing tasks. For example, state and federal contracts, and insurance companies, require that a person with an engineering license draw up their plans.

Relying on others for success has been pleasantly easy, said Linder. “But if we could have learned how to draw the engineering plans ourselves by learning the software, and gotten away with it, we probably would have done it,” he laughed. “Originally we were pretty confident of our own engineering.”

Jody has always been the most extroverted of the four male Linders, which includes father John, Josh, and Jared. Though the spokesperson, Jody has been only one spoke in the family wheel. The Linders work together as a unit and they seldom argue, said Linder. They reach consensus on work issues before proceeding and know each other like the back of their hands—all of which comes in handy when bidding against competitors.

“We’ve done pretty well with bids,” said Linder while pointing toward the work area where brother Josh was welding a $489,000 staircase. “We haven’t lost one yet because we can manufacture our staircases less expensively than others.” He also credited their current success to communication skills. They claim to answer email from architects, general contractors and potential customers “almost immediately.”

Said Linder, “It’s something we do best: We are really good at staying in contact with architects and customers. We are very good at answering questions. We help a customer design the staircase, do the engineering, and we’ll spend the extra money to help them see what the finished version will look like. We learn what they want, and we know what we can and can’t do without talking to anyone else.”

Usually working with architects in the beginning of a project, the Linders ask about budget size and give the architects various options to keep the project under budget. “If they say they have only $100,000, then I tell them what they can get for it,” said Linder. “For instance, they aren’t going to get glass steps or glass railings for that, and it won’t be clad in gold. As for options, the sky is the limit. You can do anything. We’ve been working on a design right now for a $30 million home that, as far as I know, hasn’t been done before.”

So where does Linder Enterprises go from here? The company has grown from zero to $2 million in six years. John, the 66-year-old father of the clan and primary designer, doesn’t have retirement plans. Their clients—extremely wealthy individuals, large corporations and educational institutions—aren’t affected that much by major economic downturns. They have few labor problems, and they manufacture custom product that can’t be knocked off by an overseas competitor. In other words, so far the sky is the limit—unlike Jody’s first attempt at flying.

Cost Analysis

“Labor is one of our biggest expenses. Our other expenses include engineering, the steel itself, rolling of the steel, the building, and also insurance, which is a huge expense for companies in our industry because each staircase we build is so unique. I don’t want to even tell you what we pay for insurance. It’s expensive not only because of the dangers constructing the staircase, but also installation. Our staircases are shipped via semi to the site. Sometimes you are lifting six or seven tons over a very expensive home and through a hole in the roof using a crane.” —Jody Linder of Linder Enterprises.

Wells Building

“We found the building ourselves that we’re currently in here in Wells,” said Jody Linder, co-owner of Linder Enterprises. “We needed something bigger, better, and we needed it quick. What we found in Wells was the best thing.” They had contacted chambers of commerce in Mankato, Minnesota Lake, Wells, and Mapleton searching for an adequate building. The Linders had just received purchase orders to manufacture a number of large staircases that physically couldn’t be built on the family farm. Their unique work requires a building with high ceilings and oversized doors to facilitate the safe movement of staircases weighing up to six tons.

“We talked to the City of Wells about this empty building,” said Linder of their current structure, “and we were able to rent within a day.”

As for one day having their own building, the Linders simply haven’t had the time to make those kinds of decisions. They’ve been too busy the last two years building spiral staircases to think about anything else. “We probably will (build our own) at some point,” said Linder. “But this year has been our busiest to date. Gross sales should be a little over $2 million, perhaps $2.1 million.”

State Maps

Take out a map, lay it on a table and stick pins on Washington, Texas, California, Washington D.C., Maine, Connecticut, Arizona, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. That’s where Linder Enterprises spiral staircases have been or will be sent—and more. Customers are residential, corporate, and educational. As for residential customers, the least expensive home a Linder staircase has been featured in was worth $6 million, and the most expensive, $30 million. For example, an heiress of an international business empire purchased three Linder staircases for her mansion.

“Most of our customers, like this woman, don’t want anyone to know they were our customer,” said Linder of the heiress.

Given the customer base, product price, and building codes, their staircases have to be “right on the money” as for size and quality of workmanship, said Linder. “We have made our mistakes. We made one once, got the staircase in, and discovered the curve was off about an inch and a half because of weld warp, which is caused by the rapid heating and cooling of metal.”

To fix the job, the Linders trucked the staircase back to Wells, rolled new steel quickly, figured out what went wrong, toiled literally around the clock, and was back on site only a week later. It was the fastest they had ever built a staircase.

Said Linder, “The jig was right, and should have come out right, but when you are welding half-inch plate steel, and you follow along too much on one side, it will warp no matter the thickness. Recently, we just bought a brand new welder that is supposed to alleviate weld warp. Because of building codes, we have to be within three-eighths of an inch.”

Fortunately, their one-week absence from the job site did not in any way hold up the overall construction of the expensive home, said Linder.

Another Linder

Another company helping Linder Enterprises move forward has been Linders Specialty Company of St. Paul, Minn., one of two companies in the U.S. able to produce the necessary helical-shaped steel. (Though sounding alike, the two companies aren’t related in any way.)

“Linders Specialty first came into play when we started building staircases for a new business center in Dallas, Texas, the Jenterra Atrium,” said Linder. “The staircases were six individual units stacked three high. The customer had this massive atrium and wanted matching spiral staircases on each side of the atrium.”

Fifteen-employee Linders Specialty rolled the steel. The “Wells” Linders could have used plate steel, like they had for the University of Minnesota-Duluth staircase, but that would have inflated labor costs. Simultaneously, they received a purchase order for three spiral staircases for a private estate in Wisconsin. Orders for nine staircases kept them hopping.

“So we also contracted out to Linders Specialty to help us in manufacturing some of the staircases,” said Linder. “We built the work frames for them and were up there almost every day working alongside them. And we utilized their rolling equipment.”

Each staircase requires a work frame, which Linder called a “jig.” It serves a similar purpose as a solid foundation to a home. If a jig is sturdy and built to exact dimensions—i.e., with the steps marked off accurately and the beams having the appropriate curvature—the assembly of the rest of the project usually falls neatly into place. Depending on the size of the staircase, a steel jig can cost up to $8,000 in raw material alone.

Even after Linders Specialty high-tech equipment rolls the steel to specification, often the Linders have to make more precise adjustments in order to perfect the curve. There is almost no room for error. Being off only a half-inch can scuttle an entire project. For these minor adjustments, they use heat, hydraulics and clamps.

© 2007 Connect Business Magazine. All Rights Reserved.